Art exhibit inspired by the American South

When the Stars Begin to Fall on view through May 10 at Institute of Contemporary Art Boston

As performed by saxophonist Archie Shepp and pianist Horace Parlan in a 1977 recording, the spiritual “My Lord, What a Mornin’” has an undertone of tender yearning as well as peaks of blazing, apocalyptic fervor.

Both feelings are evoked in an exhibition that takes its title from the song’s refrain: “When the Stars Begin to Fall: Imagination and the American South,” on view through May 10 at the Institute of Contemporary Art Boston. The exhibition presents a sampling of works by 35 African-American artists inspired by a real or imagined American South.

Author: Photo courtesy American Folk Art Museum, New YorkBessie Harvey’s, “The World” (1993) is painted wood, glass and plaster beads, hair, fabric, glitter, sequins, shells and duct tape.

This thread wears thin as a unifying device in some of the show’s six galleries, which juxtapose works by renowned as well as so-called outsider artists, also referred to as self-taught or folk artists, and a few who defy these categories. What makes this show absorbing is that regardless of their maker—from men and women laboring at crayon and pencil drawings while in jails or mental hospitals to art-circuit notables — many works on view are ablaze with spirit.

Thomas J. Lax curated the show for the Studio Museum in Harlem, where it debuted before coming to the ICA in February. Ruth Erickson, ICA assistant curator, joined Lax in organizing the six-gallery presentation here, which includes works on paper, paintings, videos, sculptures, and assemblages.

Painter Kerry James Marshall, 59, has made it his business to correct the “lack in the image bank” of strong African Americans in the visual arts. A pair of small paintings by Marshall shows statuesque female and male figures that suggest potent mythical characters.

Accomplished, questing Carrie Mae Weems, 52, has for decades explored the experience of being female and black in photographs, text and videos. She is represented here by three photographs from her 1992 “Sea Islands” series, set in graveyards on islands off the coast of Georgia, where for centuries black inhabitants practiced African burial customs. Weems combines photographs with excerpts from the writings of author and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston, who documented these customs, and lines from the Willie Dixon blues standard “Hoochie Coochie Man.” In one of her arresting images, a metal box spring hangs from a tree, the sides of its drooping wire frame unfolding like wings.

A place for ‘place’

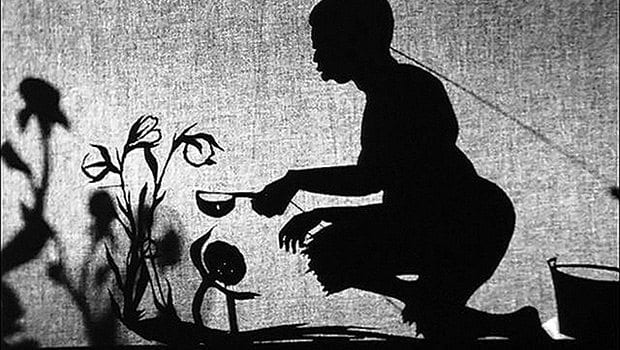

Kara Walker, 45, gained early renown with her inventive use of vintage story-telling tools such as cut-paper silhouettes and stick puppetry to recount the history of slavery, racial violence and sexual abuse. On view is her still potent 2005 video, “8 Possible Beginnings, or the Creation of African-America; a Moving Picture by Kara E. Walker,” which makes sardonic use of figures from the tales of Uncle Remus and Br’er Rabbit to recall bitter truths of the African-American diaspora, including lynchings.

The mission to reconnect with place or community and conjure an elusive rootedness drives storytellers in all media, from music and dance to the visual arts. In this exhibition, some claims of shared heritage are more convincing than others.

Among the most memorable conjurers represented here is Marie “Big Mama” Roseman (1898-2004), a herbalist, midwife and seamstress who migrated from Mississippi to Michigan in the ‘60s. All three of her trades are apparent in her luscious fabric works, an appliquéd pillow and quilted comforter, each adorned with an irresistible, baroque excess of colorful sequins, beads, and fabric flowers.

They are kin in spirit to the painting “Heaven” (1997), a hallucinatory dream of a burgeoning spring by artist-activist Benny Andrews (1930-2006) of Georgia.

Author: Photo courtesy American Folk Art Museum, New YorkBenny Andrews’ “Heaven” (1967) is oil on canvas.

Some works are curiosities, more interesting as anthropological specimens than as works of art. Yet several deeply curious works span both worlds. Take the tempera and ink drawings by JB Murray (1908-1988) of Sandersville, Georgia. Inspired by a vision of the divine, in his ’70s, he began making thousands of these small images. The row of 18 stirring, delicate drawings displayed here creates a visual progression that builds in intensity. They evoke automatic writing of the early European Surrealists in the ‘20s, who sought to express the spirit by making spontaneous marks on paper, and the seemingly random hieroglyphics of A-list abstract expressionist Cy Twombly.

A number of artists with strong academic credentials share the preoccupation with matters of spirit associated with self-taught artists. Rudy Shepherd, an assistant professor at the Penn State School of Visual Arts, makes small sculptures that he calls “Healing Devices,” and “Negative Energy Absorbers.” More impressive is his grey-on-white, stark rendering of the New Orleans Superdome (2011), evoking its harrowing days in 2005. During Hurricane Katrina thousands sought shelter in its cavernous space, where water, food and bedding were in short supply.

Chicago-based artist and activist Theaster Gates and his musical collective, the Black Monks of Mississippi, filmed their 13-minute video ,“Billy Sings Amazing Grace” (2013-14), at Project Row Houses, an arts organization in Houston’s Third Ward. Accompanied with restraint by Gates and his ensemble, Billy, an elder, delivers a simple moving rendition of the old Quaker hymn.

Sculptor Bessie Harvey (1928-1994) combined a variety of woods to represent different peoples and homelands in “The World” (1993), which she created late in life. Composed of gnarled branches, beads, hair, fabric, glitter, sequins, and duct tape, with shells for its jewel-like eyes, the exuberant figure resembles a whirling priestess. With human heads popping out from the folds of her skirts, she courses with fierce, apocalyptic energy.