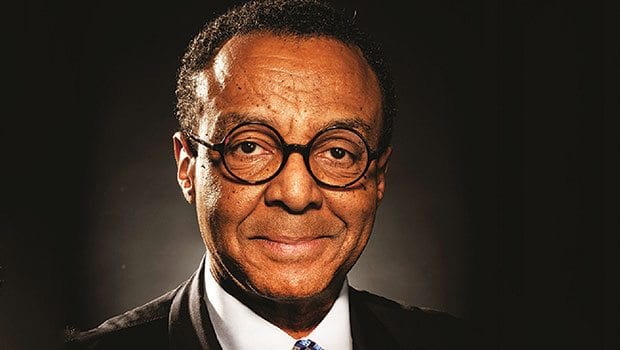

Clarence Page is a nationally-syndicated columnist and member of the Chicago Tribune editorial board. Besides those duties, the Pulitzer Prize-winner makes frequent TV appearances, including on The McLaughlin Group as a regular member of the show’s panel of political pundits.

Page makes his home in the Washington, DC area with his wife, Lisa, and their son, Grady. Here, he talks about his life, career and his best-selling collection of essays, Culture Worrier.

Kam Williams: How much of a connection do you still have to Chicago? You write for the Tribune, but live in DC.

Clarence Page: That’s right. I work out of our Washington bureau. My column is syndicated nationally, anyway. I have more of a Washington perspective than the other Tribune columnists, but I still love the place and try to get back as often as I can. And I occasionally do a locally-oriented blog item which is only printed in the Tribune.

KW: I think of you as the black Mike Royko. How would describe your style?

CP: I think every Chicago columnist considers himself to be a Mike Royko. His office was next door to mine at the Tribune Tower for a number of years. I always admired his strong voice … a very ordinary Chicagoan sitting at the bar after work going back-and-forth with his buddies about politics and this or that from a working-class point of view. I really appreciated his ability to do that so flawlessly, and in such a strong voice. So, I always tried to cultivate a voice assessing what was good for the average members of the public, and sometimes I succeeded.

KW: You always do a great job. Tell me a little about why you decided to publish a collection of essays?

CP: It occurred to me that after doing this for 30 years, from the Reagan Era to the Age of Obama, that if there was ever an appropriate time for me to publish a collection of columns, this would be it. So, I went back and reread my pieces, and I began to notice the strong trend toward social commentary interwoven with politics played in most of them, and the phrase “Culture Worrier” just jumped out at me.

KW: How do you enjoy appearing on the McLaughlin Group with John, Eleanor Clift, Mort Zuckerman and Pat Buchanan?

CP: I’ve been doing the show since about 1988. McLaughlin’s been a remarkable talent scout over the years when you think about how people like Chris Matthews, Lawrence O’Donnell and Jay Carney used to be regulars on the show.

KW: What was the most interesting and the most challenging aspects of being an army journalist back in 1969?

CP: Oh, that’s an interesting question! I will say that the difference was that when you’re an Army journalist, as opposed to a civilian correspondent covering the military, you’re very often either a public relations agent or expected to perform that role, with a few exceptions, such as reporters for Stars and Stripes. I would say that one of the most unexpected benefits of that job was being taught to never try to cover anything up, but rather to get any bad information out right away, so that there would be nothing more to come out later. This was a wonderful lesson to be taught because often the effort to cover up a story becomes a bigger story than the original one.

KW: You suffered from ADD, but it obviously didn’t prevent you from having a very successful career as a journalist. How did you overcome this difficulty or turn it into a strength?

CP: I didn’t know I had ADD, because it hadn’t been invented back then. For what it’s worth, like a lot of others with ADD, I’ve been able to succeed simply by trying harder.

KW: What did winning a Pulitzer mean to you?

CP: One thing about winning a Pulitzer, it means you know what the first three words of your obituary will be: Pulitzer Prize-winner. [Chuckles] After winning the Pulitzer, I couldn’t help but notice how people suddenly looked at me with a newfound respect, and would say, “He’s an expert.” On the negative side, I developed a terrible case of writer’s block for awhile, because I felt like readers would expect every one of my columns to be prize worthy. I spoke to a number of other Pulitzer winners who had the same problem, a creative block that had them hesitating. How do you get past the writer’s block? Nothing concentrates the mind like a firm deadline, and a little voice in the back of my mind reminding me that, “If you don’t write, you don’t eat.” Listen, we all want to be respected and appreciated, but when you get a big honor like that, people start to look for your work in a new way with higher expectations. Today, the best thing about having won is when I get a nasty comment from some internet troll I can remind myself of the Pulitzer and say, “Well, somebody appreciates me.”

KW: What, in your view, is substantially culturally different in the U.S. today versus say March 3, 1991, Rodney King Day? And what do you believe is the single greatest piece of evidence that progress is being made toward a society that provides equality of opportunity and treatment under the law, regardless of race, ethnicity or gender?

CP: Good question. First of all, I would say that our cultural divides are less racial and more tribal. We’re trying to reduce racial barriers to opportunity while at the same time not creating artificial quotas in regards to race. Today’s tribal politics is more attitudes and values-based than back in the olden days when it was something we strictly associated with ethnicity.

KW: What do you see as the most critical domestic concern that needs to be addressed by our national government?

CP: I would say environmental protection is our most important long-range issue. In the shorter term, as well as the longer term, I’ve always said our biggest challenge is in education, which has become even more challenging because of income inequality and wage stagnation. We haven’t confronted the fact that people who get their income from capital investments have benefited while ordinary workers who rely on salary have not. So, the income gap is getting worse. But Washington is in gridlock, politically, and I’m pessimistic about our making any major improvements over the next couple years.

KW: When you think about your legacy how would you like to be remembered?

CP: When I posed that question to retiring Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, he looked up as if he were surprised, but he quickly responded, “That he did the best he could with what he had.” It was remarkably humble, but to the point. That’s how I’d like to be remembered, too.

KW: Is there any question no one ever asks you, that you wish someone would?

CP: What would I have done, if I had not become a political writer? I wanted to become an entertainment writer. I’ve always been fascinated by showbiz as much as I was by politics.