Editor’s note: The federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) agency regulations rule that projects that create segregated housing, even unintentionally, violate the Fair Housing Act.

Federal laws passed in the 1960s were supposed to eliminate racial discrimination in America. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 made it unlawful to discriminate because of race in education, employment and places of public accommodation. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 eliminated impediments to black suffrage, especially in the South. And the Fair Housing Act of 1968 was supposed to end racial segregation in housing. Conservative judges have been trying to rescind these civil rights protections ever since they were instituted. The Fair Housing Act has now become a special target, and has been accepted for review by the U.S. Supreme Court.

In the early days, intent to discriminate was relatively easy to establish. Landlords would violate the law by publishing “for rent” advertisements with discriminatory code words. In many cities, interracial test teams would determine whether an apartment that was already rented, according to the landlord when the applicant was black, suddenly came on the market again for a later white applicant. As housing proposals became more complex, the issue of intent became more difficult to prove.

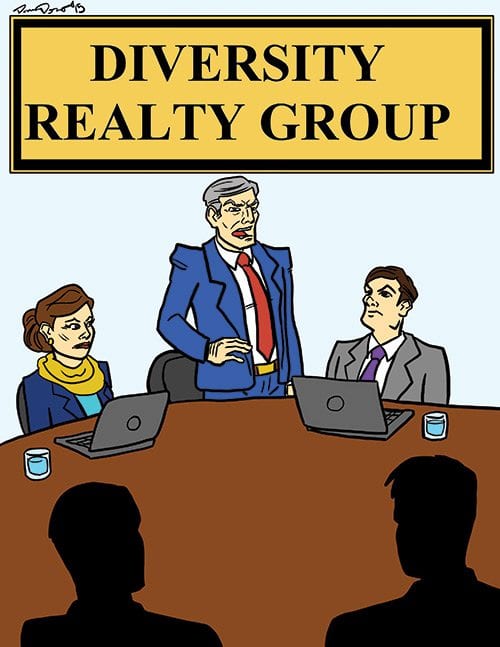

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, responsible for administering the Fair Housing Act, resolved the problem quite simply. They ruled that the law was not intended to bar only intentional discrimination. Any policy that unjustifiably perpetuates housing segregation, regardless of the intent, is a violation of the Housing Act. HUD has held this to be true whether the perpetrator is a bank, a real estate developer or a government agency. This is referred to as the “disparate impact” standard.

Discriminatory intent issues usually arose in the rental or acquisition of existing properties. Disparate impact disputes usually resulted from proposed real estate projects that depended on financing under special HUD investment programs that benefit the developers. For decades the federal courts have sustained HUD’s disparate impact standard.

According to ProPublica, a non-profit organization in Texas with the objective of achieving integrated housing has sued the state’s housing authority over providing tax credits for affordable housing primarily to projects in black neighborhoods. As a result, blacks seeking affordable housing would have to live in segregated neighborhoods. The Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs lost in the lower court and has appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court which has taken up the case.

It is rare for the U.S. Supreme Court to accept a case on appeal. The court accepts only about 80 of 7,000 cases appealed every year. One of the ways to beat those odds is for the federal appeals courts to have conflicting legal opinions. However, according to ProPublica, all 11 of the federal circuit courts of appeal have accepted the principle of disparate impact. There is no judicial conflict. It is reasonable to conclude, then, that conservatives on the bench feel strongly about the issue of disparate impact and want to reverse the law.

HUD provides financial benefits to developers who agree to build racially integrated communities. Those who challenge that objective should then willingly surrender the benefits. It would be truly oppressive for the Supreme Court to rule that the government cannot establish incentives to achieve the goal of racial integration in housing. The nation recognized in 1968 that segregated housing is contrary to the principal of equal rights. The Fair Housing Act would be an unacceptable remedy if it failed to curtail the further implementation of segregated housing, even if it was inadvertent.