The movie Selma is now playing to great critical acclaim at theaters across the country. However, people inconvenienced by the obstruction of the Edmund Pettus Bridge by protesters back then on Bloody Sunday, March 7, 1965 were undoubtedly not so understanding. Their response was similar to the angry reaction of commuters who expressed hostility over the disruption on Interstate 93 recently by those supporting the “Black Lives Matter” protest.

Critics have referred to the demonstrators as anarchists for having delayed by about one hour the privilege of an uncomplicated commute. During the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s, those campaigning for the elimination of racial discrimination were often branded as communists. That was a very powerful epithet during that era when America was in the Cold War conflict with the Russian Empire.

There is no indication as yet that the nation acknowledges the severity of the problem of police abuse of blacks. Criticism of grand jury decisions that exonerate the police for killing unarmed black men has been countered by the publication of complimentary news stories and op-ed pieces about the heroism and stellar performance of the police.

Except for the young, like those who dare to disrupt highway traffic in protest, public reaction is similar to the lack of interest in the anti-lynching laws. Before the Civil Rights Movement of the ‘50s, black leaders tried for decades to pass anti-lynch laws. The effort never succeeded because lynching was treated as a murder case to be tried in state court. Yet those who lynched black men were never convicted in the South.

Blacks argued that lynching victims were denied their constitutional rights, essentially those provided by the 14th Amendment, so such cases should have federal jurisdiction. However, since the lynching cases proceeded under the color of law in the state courts, most Americans had little interest in the matter, and no anti-lynch law was ever passed by Congress.

Even though an estimated 3,446 blacks were lynched between 1882 and 1968, members of Congress believed that the preservation of states’ rights was more important. It now appears that history repeats itself. The objective today is to protect the police and the grand jury system regardless of its flaws.

Public support for the grand jury system provides an unjust protection for abusive police officers. As in the general failure to support the anti-lynching laws, the color of law passivity about grand juries leads to injustice. The decisions of grand juries that favor the police cause one to wonder whether there are any reasonable limits on police conduct.

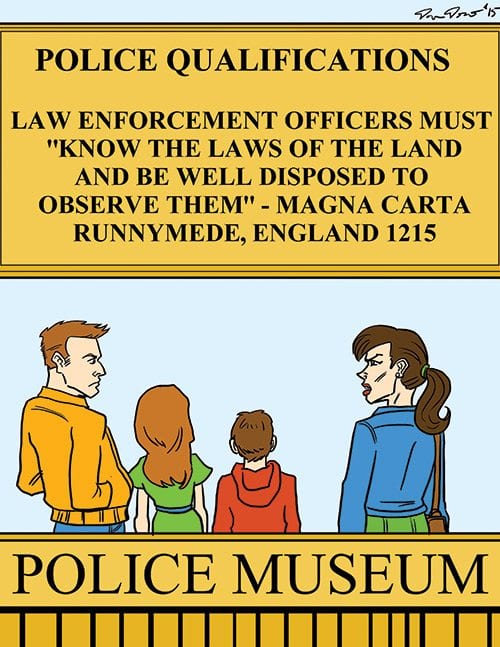

Police violence has been a perennial problem. When British noblemen challenged the authority of the crown 800 years ago, they included directives in the Magna Carta to mollify the conduct of law enforcement officers. That historic document stated “justiciaries, constables, sheriffs or bailiffs” in order to be appointed, must “know the laws of the land, and [be] well disposed to observe them.”

The Magna Carta, executed at Runnymede, England in 1215, was the precedent for the Bill of Rights and the right of judicial review that are so critical to Anglo-American jurisprudence. Yet protests against police violence in America continue 800 years later.