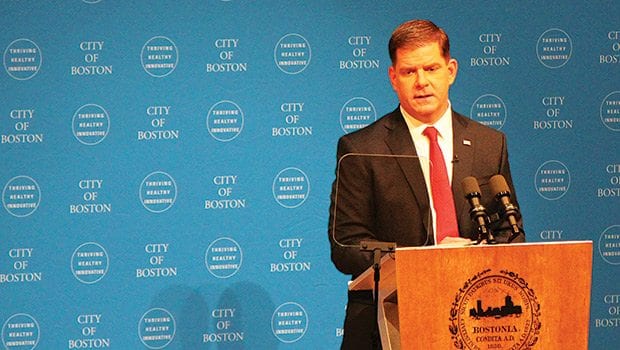

Mayor Walsh touts gains in diversifying city leadership, pledges to work on education, housing issues

Author: Mayor’s Office Photo by Isabel LeonWalsh tours the city’s new homeless shelter on Southampton Street. Currently the shelter can house 100 guests each night and upon completion will house upwards of 400 individuals.

Mayor Martin Walsh came into office last January with promises to make government more transparent and more diverse, and has largely fulfilled those promises, with actions that include appointing a cabinet and police leadership that are 50 percent people of color, auditing the Boston Redevelopment Authority and conducting a public process to establish criteria for the next school superintendent.

Walsh has earned praise from many in the black community for his more inclusive cabinet appointments and for what some see as a focus on issues that affect blacks, Latinos and Asians in Boston.

His first year has not been without controversy and challenges. His decision to close the structurally deficient bridge to the Long Island homeless shelter left many without services and set in motion a contentious battle over siting of a new shelter and services.

Now entering his second year in office, Walsh is mapping a course to combat some of the city’s most intractable problems: unequal schools and a high cost of living that has many Bostonians struggling to maintain a toehold.

“For too many of our neighbors, quality schools, affordable housing and a living wage remain out of reach,” Walsh said in his State of the City address, delivered at Symphony Hall last Wednesday.

Education

Walsh earned high marks earlier this month with his announcement that Boston elementary and middle schools will lengthen the school day by 40 minutes — a change that will add the equivalent of a month of learning time to each school year. He also created an advisory council to strategize the implementation of universal pre-kindergarten in Boston.

He has received mixed reviews for his process of selecting a new school superintendent to replace interim Superintendent John McDonough. While public meetings have been held to solicit community voices in the selection process, that process has dragged on for more than a year.

“The community wanted to have input into who would be the next superintendent,” Walsh commented. “We went around and met with community groups and student activists and parent groups to find out what they want to see in the next superintendent.”

His overarching goal with the schools, he says, is to raise the performance level in all city schools so that all children have access to good quality schools.

“I think we have more work to do around underperforming schools,” he said. “I think we have more work to do around school buildings and facilities. I think we’ve done some things really well. I think there’s a lot of room for improvement in other areas.”

Another area in which Walsh says he wants to see improvement is in the number of African American teachers in the Boston school system. Despite a desegregation court order mandating that blacks make up 25 percent of the city’s teachers, just 22 percent of the city teachers are black. Blacks and Latinos make up 89 percent of the school system’s students. Walsh told the Banner his administration will do better.

“I think the city’s done a terrible job in diversifying the school department,” Walsh said in a recent interview with the Banner. “I think it goes back years. First of all, we shouldn’t have a court order telling us we need to have teachers of color. There’s just something fundamentally wrong there. I’m looking to go beyond the 25 percent.”

Affordable housing

Walsh’s housing plan, released in October, revolves around producing 53,000 new units of housing in Boston over the next 15 years to keep pace with an expected population increase of 91,000. While Walsh says there’s no certainty that the increased housing supply will make homes in Boston more affordable, the mayor is planning to make 250 parcels of publicly-owned land available for the development of affordable housing.

“The housing plan was really focused on creating more opportunities for affordable housing and workforce housing, but also, there’s a component of it for low-income housing,” he said. “As the federal government cuts funding for affordable housing, we’re not going to have that housing stock. We have to come up with ways of creating new affordable housing stock.”

Criminal justice

One of the more challenging areas Walsh has had to contend with in recent months is the increased focus on strained relations between the city’s police force and black teenagers, many of whom complain of frequent stops and harassment by Boston officers.

A study of police data on pedestrian stops found that blacks were more likely than whites to be stopped, questioned or observed by police, who record data on their interactions with the public in a Field Intelligence Observation database. As the Black Lives Matter movement has been increasing awareness among the general public of inequalities in policing, Boston police practices have come under increased scrutiny.

Walsh says that police relations with black youth are better here than in cities like New York and Ferguson, Missouri, where police killings of unarmed blacks have made national news, but acknowledged that there are challenges to building better relations.

“There are clearly tensions between young people and the police,” he said. “How do we get that trust back on both sides? I think that’s going to be the biggest challenge for us in the coming year — building that trust.”

Walsh said his administration’s My Brother’s Keeper initiative, coordinated with the national initiative launched by President Obama, will create an opening for tough conversations about race. The city also has been approved for a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to facilitate conversations around race. (The dollar amount of the grant has not yet been finalized.)

“The police will be part of that conversation,” Walsh said. “There are other pieces of the conversation we need to have around race. When you look at board rooms, you don’t see enough people of color. When you look at government offices, you don’t see enough people of color. In positions of development, there aren’t enough people of color. We certainly don’t have enough people of color as teachers in the city. So there’s a lot of room to grow. And I think we’ve laid a good foundation down this year.”

Cabinet diversity

Early in his administration, Walsh drew fire from some in the black and Latino communities for a perceived slow start in building a diverse cabinet. But by the end of the year, half of his leadership team members were people of color: Chief of Economic Development John Barros, Chief of Health and Human Services Felix G. Arroyo, Chief of Staff Daniel Koh, Chief of Education Rahn Dorsey, Chief of Civic Engagement Jerome Smith, Chief of Innovation and Technology Jascha Franklin-Hodge and Chief of Arts and Culture Julie Burros.

In many ways, Walsh’s approach to filling cabinet posts is indicative of his leadership style. It took a while, but he kept his word.

“People were frustrated by the timeliness of how we ramped up the cabinet, but by taking our time and doing it correctly we got to the goal we wanted to get to,” Walsh commented. “We took our time and made sure we went through the process and brought people in. You can see the benefit of that now in the city.”