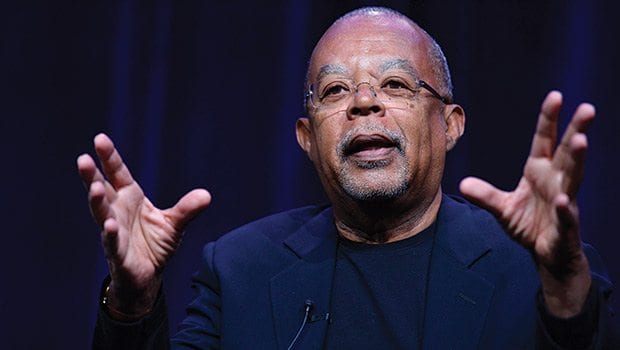

Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr., is the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and Director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University. Emmy Award-winning filmmaker, literary scholar, journalist, cultural critic and institution builder, Professor Gates has authored 17 books and created 14 documentary films, including Finding Your Roots, season two, now airing on PBS.

His 6-part PBS documentary series, The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross (2013), which he wrote, executive produced, and hosted, earned the Emmy Award for Outstanding Historical Program — Long Form, as well as the Peabody and NAACP Image Awards. Having written for such leading publications as The New Yorker, The New York Times and Time, Dr. Gates now serves as editor-in-chief of TheRoot.com, while overseeing the Oxford African American Studies Center, the first comprehensive scholarly online resource in the field.

Professor Gates’s latest book is Finding Your Roots: The Official Companion to the PBS Series, released by the University of North Carolina Press in 2014. Here, he talks about Finding Your Roots: Season Two, now available on DVD.

Kam Williams: Congrats on another fascinating season of Finding Your Roots. How did you pick which luminaries to invite to participate in the project? Did you already have an idea that they might have an interesting genealogy?

Henry Louis Gates: No, we picked them cold. I have a wonderful team of producers. To tell you the truth, first, we just fantasize. Then, we sit down in my house with a big peg board with the names of all the people who said “Yes.” So, we never know whom we are going to get in advance.

KW: How do you settle on the theme of each episode? For instance, you did the one on athletes with Derek Jeter, Billie Jean King and Rebecca Lobo, and the one on chefs with Tom Colicchio, Aaron Sanchez and Ming Tsai.

HLG: Usually, we first do the research and film everybody, and then organize the episodes internally. For instance, Episode One was called, “In Search of Our Fathers.” You might wonder, what does Stephen King have in common with Courtney B. Vance? Well, Stephen King’s father left when he was 2, and Courtney never knew his father. He was put up for adoption. And frankly, that’s my favorite kind of story, when it’s counter-intuitive. That’s why we’ve organized the episodes around those two principles.

KW: The subject of our roots is fascinating, as shown in your television program on PBS. I’m wondering what you found to be the singularly, most-interesting discovery in your research for Finding Your Roots 2?

HLG: That’s tough to say, because each story has something dramatic and interesting. Take when Ming Tsai’s grandfather fled China after the revolution, all he took besides the clothes on his back was one book, the book containing his family’s genealogy. Isn’t that amazing? He was willing to flee to a whole new world, learn a new language, and start over in a new culture only if he had his family tree with him. That’s heavy, man! It’s like he was saying, “I can do anything, as long as I have my ancestors with me.” I really admire that. And consequently, we were able to trace Ming’s ancestry back to his 116th great-grandfather.

KW: Whose roots were you able to trace back the farthest?

HLG: Ming Tsai’s, without a doubt. We’ve traced several people back to Charlemagne, but Ming’s goes back to B.C., because of the Chinese penchant for keeping fantastic genealogical records.

KW: It seems that your guests have a variety of reactions as each story and new facts are revealed. Whose reaction to an uncovered story surprised you the most?

HLG: Anderson Cooper, without a doubt. I told him that his 3rd great-grandfather, Burwell Boykin, was a slave owner. First of all, Anderson was very saddened and disappointed that he descended from a slave owner. But his ancestors were from Alabama, so I told him that was very common. I don’t think you inherit the guilt of your ancestors. We merely reveal whatever we find, without making any sort of judgment. What your ancestors did is what they did. That’s not on you. Anyway, Burwell Boykin had a dozen slaves, according to the 1860 Census. And one of them kept running away. To punish him, he locked him in a hot and humid cotton house. Can you imagine? When Burwell let Sandy “Sham” Boykin out the next morning, the slave grabbed a hoe out of his master’s hands before beating him to death. We found the story in a diary kept by one of Anderson’s ancestors, and then we verified it in the court records which showed that, sure enough, a slave named Sandy Boykin had been hanged in 1860.

KW: Are you aware of the research work of Professor/Researcher Roberta Estes and her research into accurate testing for Native American genetics?

HLG: No, I’m not. I would love to learn about what she’s doing. We’re always fascinated with Native American ancestry, and we’ve found two surprising things about our guests. First, that very few have any significant amount of Native American ancestry, black or white, although Valerie Jarrett did have 5 percent, and we found her 6th great-grandmother, by name, and the Native American tribe that she was part of. But rarely do we find an African American with even 1 percent Native American ancestry.

KW: Has anybody ever tried to disagree with their DNA analysis?

HLG: No, but some people were shocked, particularly African Americans who believed they had Native American ancestry. They’re always disappointed. [Chuckles]

KW: Did any of your subjects ask you not to reveal something you found out about their family?

HLG: No, although I’m sure a few people would like to do so, if they could. But we’re PBS. We’re independent.

KW: Do you ever answer queries from everyday people who need help with genealogical puzzles and other obstacles to fleshing out their family trees?

HLG: Yes I do, in two forms. At TheRoot.com, we answer a question a week for African Americans who have a genealogical quandary. That’s co-written with the New England Genealogical Society. And at Ancestry.com, the genealogist there and I write a weekly column that’s on the Huffington Post.

KW: What would you say carved out this path for you?

HLG: The fact that when I was 9-years old, on the day that we buried my grandfather, Edward St. Lawrence Gates, my father showed my brother and me a picture of Jane Gates, the oldest Gates we’ve ever traced, then or now. It blew my mind! She was born in 1819 and she died in 1888. I’m looking at her picture right now. She was a slave and a midwife. I was just so amazed. Between looking at my grandfather in the casket, which was very traumatic, and seeing my father cry for the first time, which was also very traumatic, and trying to figure out how in the world someone who looked like me could have descended from someone who could have passed for white, and then finding out that my great-great grandmother was a slave, intrigued me. So, the next day I interviewed my parents about my family tree. And I’ve been hooked ever since. [Laughs] And that’s a true story.

KW: What surprised you the most about your own genealogy?

HLG: The fact that I was 50.1% white and 48.6% black.

KW: Do you go about gathering genealogical information about African Americans very differently from the way you do for other ethnicities? How do you get past the obstacle of slavery?

HLG: Yes, we do, because African Americans generally weren’t identified by name in the census prior to the abolition of slavery. So, we start with the 1870 census, which is the first in which blacks appear with two names. Then you go back to 1860, and see whether there were any slave owners with the same surname, since, more often than not, most emancipated slaves kept the surname of their former owners. Ironically, the key to finding one’s black ancestry during slavery often involves finding the identity of the white man or woman who owned your ancestors. That’s quite a fascinating paradox.