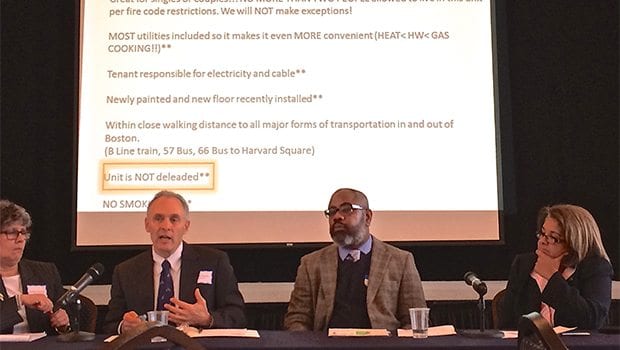

Mayor Martin Walsh and Health and Human Services Chief Felix G. Arroyo at a summit on lead poisoning held by the city’s Office of Fair Housing and Equity. (Banner photo)

Massachusetts law dictates that any housing unit inhabited by children under age 6 must be safe from lead-based paint hazards. That means that if the building was built before 1978, the year lead paint was banned in the U.S., the owner must have it inspected and deleaded if children or pregnant women live there, or provide certification that there is no lead present.

In addition, fair housing laws prohibit owners from refusing to rent to families just because they have young children.

While the laws are aimed at both protecting children and guaranteeing families equal access to housing, results are not always as intended. Not only are children continuing to be exposed to lead, families are illegally steered away from apartments that may contain lead.

The health and discriminatory impacts of lead paint were addressed at a city-sponsored daylong “lead summit” last week that drew together city and state officials, academic experts and stakeholders from the public health, housing and nonprofit sectors. The summit, titled “Childhood Lead Exposure and Housing Discrimination: Both Bad for Your Health,” was organized by the city’s Office of Fair Housing and Equity and timed to coincide with National Lead Poisoning Prevention Week 2014.

In Boston, lead is a particularly acute problem because ninety percent of the city’s housing was built before 1978. Lead still lurks today in many of these older homes.

If lead paint is cracked and peeling or if home renovations are done without proper precautions, lead can be released in paint chips and dust and easily absorbed by toddlers and children as they crawl and play near floors, walls and wood-framed windows. Ingestion of lead or inhaling of lead dust poses a hazard to anyone, but especially young children, whose bodies and brains are still developing, and pregnant women who can pass lead poisoning to their fetuses. Lead exposure can damage the brain, kidneys, nerves and blood, and has been shown to lower IQ and cause academic and behavioral problems.

In addition to covering housing discrimination and deleading resources and training for contractors, renovators and homeowners, the summit included academic and medical experts who outlined some alarming data on the harmful effects of even low levels of lead exposure.

“We’re doing better, but don’t be fooled,” said Dr. Sean Palfrey, clinical professor of pediatrics and public health at Boston University School of Medicine and as run lead poisoning prevention programs in Central Massachusetts and in Boston since the late 1970s.

Palfrey said that while only a handful of children are severely poisoned and hospitalized each year, far more are affected by lower levels of exposure that can cause lower IQ, difficulty paying attention and language acquisition difficulty.

His lead poisoning prevention programs work to educate the public on simple measures such as washing surfaces with Spic and Span or liquid soap to remove dust from window wells and corners — anyplace children’s hands may touch. While there are other sources of lead exposure, paint is still the cause of about 80 percent of lead poisoning, Palfrey estimated.

Current state law requiring home inspections when a child’s lead level is found to be above 25 micrograms is based on “old science,” Palfrey said in an interview. He believes the level should be lowered, but changing the law is resisted by landlords and real estate agents.

“It’s a problem we know how to solve. We just haven’t had the gumption to do it,” he said.

A panel on lead-related housing discrimination featured Nancy Schlacter, executive director of the Cambridge Human Rights Commission; Barbara Chandler, senior advisor on civil rights and fair housing at the Metropolitan Boston Housing Partnership; William Berman, clinical professor of law and director of the Suffolk University Law School Housing Discrimination Testing Program; John Smith, enforcement and compliance manager at the Fair Housing Center of Greater Boston; and Jamie Williamson, chair of the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination.

Panel members discussed both the legal requirements landlords must keep in mind about lead paint and the barriers to actually getting apartments deleaded.

“This is the most intractable area of discrimination we see,” said Berman, whose HUD-funded program sends pairs of “testers” to inquire about apartments, one who mentions a child under 6 and one who does not. Discrimination against families because of lead paint is the most common problem they find.

Technically, families are supposed to be able to view and select any apartment on the market that they can afford, deleaded or not. If they choose an older apartment, the landlord must present a certificate of deleading — or undertake the deleading process immediately, before the tenants move in.

In reality, many landlords balk at the expense and labor of deleading. Owners often advertise apartments as “not deleaded” or “great for singles or couples” to alert families with children to not inquire. Real estate agents may simply tell families the units are not available. If they are aware this is illegal, they won’t say outright that no children are allowed, but instead will discern whether apartment-seekers have children by asking seemingly innocuous questions, like “How many people will be living in the unit?” and then quietly deny them the chance to view units that may have lead paint.

The upshot is that families have far fewer rental options, and lead paint issues remain unabated.

There is a significant financial incentive for landlords to discriminate, Berman explained, and a “permissive culture” that makes it seem okay for property owners to say out loud that they don’t intend to rent to families with children.

Berman’s group also inspects posted apartment ads, and finds that at least 57 percent contain wording that is meant to discourage families with children, a practice that violates fair housing laws.

Chandler said another important factor is that most apartment-seekers need to find housing quickly. People using Section 8 vouchers, for instance, often have a limited search time and may not be able to wait for an apartment to be deleaded, even if landlords are willing to do it.

Williamson added that even housing authorities sometimes advise clients to “keep looking, because time is of the essence” if they’re told a landlord can’t accept Section 8 because of lead paint. This is patently illegal and clearly irks Williamson.

“Information is power,” she said. “We need to educate people. If you ask about deleading and they say no, don’t just hang up.”

Politicians and the general public may be unwilling to push for stronger enforcement, finding small landlords sympathetic parties, as evidenced by the popular support for repealing rent control in 1994, a movement bolstered by ads featuring “mom and pop” landlords fretting about expenses.

Chandler expressed little patience with the homebuyer who acquires a triple-decker, counting on rental income to pay their mortgage, but does not treat it like the small business it really is, with rules and regulation that come along with business ownership.

“Sometimes landlords will say, ‘I’m a grandfather, and I’d really hate to endanger a tenant’s child,’” she said. “But if they really cared about children, they’d delead.”

As for solutions, panelists suggested a combination of enforcement, stronger laws and greater financial assistance to property owners who delead. Some myths about the costs and effort of deleading need to be dispelled as well.

“What people don’t understand is, it’s not a $30,000 job anymore. The average is less than $8,500,” Berman said. He noted that property owners in Boston can receive forgivable loans of $8,500 from the city. There are also a number of other grants and credits at the city, state and federal level for deleading.

Williamson supports adopting a law to require any housing rented to anybody to be lead-compliant. The law could allow some time, for instance a three-year phase-in, she said, and some financial incentives — but would have to be pushed hard to overcome political resistance.

“It’s a public health risk. I don’t know if you’ve seen what lead paint does to a child,” she said, adding, “As long as it’s only affecting the poor, it’s not going to be a priority. We have to make it a priority.”

The Walsh administration is introducing actions to reduce lead hazards in Boston. Mayor Martin Walsh made a brief speech at the lead summit and announced a five-point plan involving several city agencies. The plan includes deleading of 400 housing units over the next five years; educating 2500 at-risk residents on fair housing and lead awareness; conducting 325 lead inspections in high-risk units; training and licensing 500 contractors in lead safety during renovations; and training 250 homeowners in do-it-yourself moderate-risk deleading.

“We will use data to focus our efforts on most at-risk neighborhoods,” Walsh told the audience. “This issue is important for so many reasons. It’s an education issue, it’s a jobs issue, it’s an environmental justice issue, it’s also a health and housing issue. It affects our shared progress. So we need to have a hand in the solution.”

For information from the Boston Public Health Commission about lead poisoning prevention, see http://bit.ly/1wywseR. For information on grants available to help pay for deleading, see the Department of Neighborhood Development’s Lead Safe Boston brochure at http://bit.ly/1w7BTQD. To read about National Lead Poisoning Prevention Week, see http://www.cdc.gov/features/leadpoisoning.