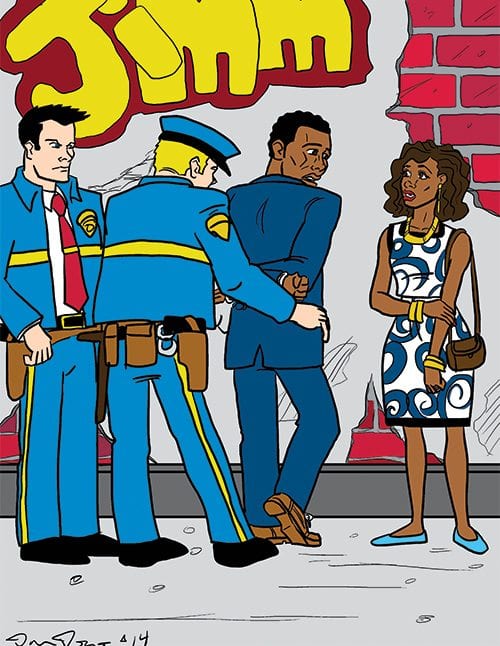

Many people have endured the agony of being aggressively accused of various offenses when they are actually innocent. That is how a young black man feels when he is the victim of the police stop-and-frisk routine. The policy requires that the police must believe the suspect has committed a crime or is about to do so in order to justify a brief, and often humiliating detention. Passersby tend to view such incidents as deserved apprehensions of law breakers.

However, a study by the American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts of such interrogations in Boston between 2007 and 2010 found few beneficial results. Of 204,000 stops recorded in the police department’s database, only 2.5 percent resulted in the seizure of illegal contraband or arrests. This is not a satisfactory success rate for a very invasive practice.

Some citizens insist that the stop-and-frisk procedure is an essential element of good police work. However, prior to 1968 the police in America lacked the legal authority to stop-and-frisk anyone without probable cause to make an arrest. In the case of Terry v. Ohio, the U.S. Supreme Court extended the right to stop and interrogate a person on the street if the police have a reasonable suspicion that the person has committed a crime or is about to do so. An external pat down is permissible only if the officer believes the person “may be armed and presently dangerous.” Only when a frisk reveals a concealed weapon is a search permissible.

As in New York, the ACLU study reveals that stop-and-frisk in Boston has not been a successful anti-crime deterrent. In fact, the disproportionate hassling of young black men by the police is destructive of satisfactory police-community relations. According to the ACLU report, 63 percent of its 204,000 interrogations were of blacks who constitute only 24 percent of Boston’s population.

Apologists for police policies assert that the greater number of stop-and-frisks occur in black high crime areas, so it is expected that blacks would be more frequently targeted. In 2004, three years before the period covered by the ACLU report, the Boston Police Department was sufficiently concerned about complaints of racial profiling that they conducted a telephone survey to determine citizens’ attitudes toward the police.

The issue was to inquire whether Boston police officers are viewed as fair and respectful. While residents of most neighborhoods responded in the affirmative — 71.7 percent — the results were quite different in the black areas. Only 41 and 54 percent respectively of the residents of Roxbury and Mattapan agreed. Reporters also found countless stories of alleged abusive behavior by the police.

The pent up anger provoked or energized by stop-and-frisk prevents the development of congenial police-community relations. Such cooperation is a useful relationship for fighting crime. Inadvertently, stop-and-frisk as now employed actually sabotages sound law enforcement.

The damage to race relations caused by stop-and-frisk is hardly worth the paltry arrests that result. Police departments on their own should reinstate the standard for stop-and-frisk that was the law before the 1968 Terry case. The police officer must have probable cause for arrest. A bulge in the pocket that appears to be a concealed weapon would still justify an external pat down.

The Supreme Court decision in the Terry case merely establishes that the easier standard for stop-and-frisk is constitutionally acceptable. However, the court does not require police departments to implement the new standard. African Americans are fed up with police harassment. Adoption of the standard before Terry would help to relieve the tension.