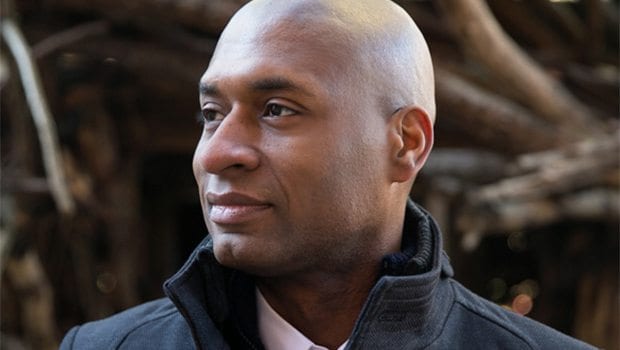

The New York Times columnist Charles Blow came out with “Fire Shut Up In My Bones,” in late September, and in this book he tells the riveting and harrowing story of a childhood spent in rural Louisiana. Raised in poverty, Blow went on to attend Grambling State University and achieve a level of recognition as a journalist with few peers.

In the book, he describes in frank detail his sexuality, race matters, and a family and environment in which guns were often used to settle disputes. How he went on to have a career and a family is a unique narrative of resilience, intellect, faith, and luck.

Blow’s contribution to the national debates taking place on race, sexuality, and poverty is better understood through his very explicit and unflinching look at his childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood. The book is inspiring, as it compels readers to examine their own lives and think long and hard about possibility and its alternative: failure.

He is currently on a national book tour, and took time to speak with the Bay State Banner about his work and what led to its creation.

Why now?

I’ve been working on the book for nine years, and in 2009 I had read that two little boys, eleven years old, had committed suicide, just ten days apart, and that there was homophobic bullying involved. I knew that story intimately. I had also thought of suicide at an early age. I realized I knew how to write that story. They cannot express the magnitude of their sorrow, but I could, and I wanted to write as well that you can still have a life.

The title of the book is from the book of Jeremiah: “But if I say, ‘I will not mention his word or speak anymore in his name,’ his word is in my heart like a fire, a fire shut up in my bones. I am weary of holding it in; indeed, I cannot.” Who is the “he” in reference to your book?

For me the “he” is the truth. I am speaking of “the fire” as the truth. Telling the truth, being honest.

Have any family members reacted with surprise or anguish or anger to the book? Your kids who are now teenagers?

I still talk to my mom and my brothers! Look, it was a lot for them to swallow all at once. I’ve had 44 years, it took them by surprise. With my kids? We have family meetings, and I gave them the first draft to read, and told them the broad outlines of the book. They were nonplussed by the whole thing. And then we had another family meeting, I wanted to be sure that they were OK. I gave them each a printed copy a year later. I’m not sure the younger ones read it. But the older one read it in one night, and his only comment was, ‘Why not develop my mother’s character more?’ I thought, ‘Are you editing me?!’”

Your writing in The New York Times benefits enormously from your use of evidence in charts. You write of developing charts back in the day when you were starting out as a visual journalist at the Shreveport Times. How did you develop the idea to use evidence to support your opinions?

It’s a fluke that I became a columnist. The Times was using freelancers for opinion charts, and I said to my editor, ‘Take that money and make me the guy who does that stuff.’ He suggested I add 400 words to each chart, and that was it. The focus shifted to the writing with the chart as evidence.

Where does your resilience come from? You write that you were “fortified by trauma.” Can you say more about that?

James Baldwin said, ‘Anyone who has ever struggled with poverty knows how extremely expensive it is to be poor.’ It builds a certain level of resilience. For me, too, the example of resilience was my mom. I didn’t think she ever slept. She was constantly working. Then she went to school to better herself and became a teacher, and the benefit of education was no longer an abstraction—we had more material goods. Her grit and blood made that possible. It’s like this: Some may have more advantages than you, but no one has more hours in the day. My mother thought that anything was possible. Her grandparents who raised her—she got it from them.

Did you ever consider a novel rather than a memoir?

No, novels scare me to death. I recognize the protective quality they offer a writer, but I’m not afraid of sharing. There is no fear in this for me. The only fear is completely literary: Will people like the writing?

When did you realize you wanted to be a writer? You write about a professor at Grambling who encouraged you. How about before college?

I never thought of writing as a profession you could do to feed yourself. Even when I got older, I thought more of graphic design and would not say I was a writer. I had to learn to relax and remember my voice, and that I could hear the music. It’s like swimming, you have to have confidence to do it.

How do you control your space and what is your self-identify at the NYT?

It has to be comfortable for me. Sometimes I think I’m ‘the black guy’ in the room, but then I remember I’m also the only southern guy, and that I have a southern aesthetic. I think about the kid I was, and write about the disenfranchised, the working poor, teachers who were important to me in school and my family.

Given your phenomenal achievements, how do you maintain your humility? At one point in the book you describe wanting to mimic Prince Charles when you were in college.

You don’t write in front of a crowd, you don’t have an audience. For me it’s easy to hide from all that hoopla. I go out and do my laundry, fold clothes. I’m a regular guy in the neighborhood in a sweatshirt with his coffee.

Finally, what words of wisdom—what road map—can you offer youth these days who grow up in urban poverty, like here in Boston, so that whatever it is you did is something a person wanting to see himself or herself as you or like you in five or ten years can do?

I like to say to people that life is a hill. You can climb this hill or stay at the bottom. You have to make a choice. Waiting, sulking—those aren’t options. You have to make an action.