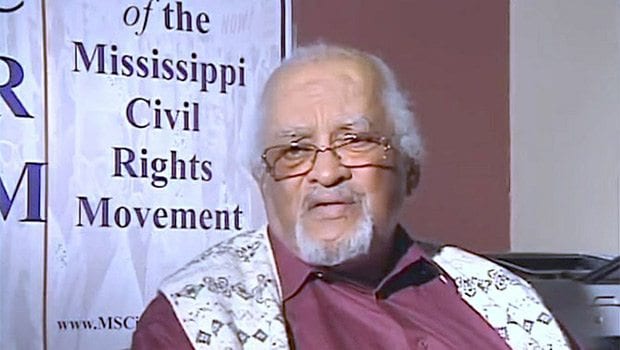

Veteran civil rights activist and leader in Mississippi’s Freedom Movement, Owen H. Brooks died in Jackson on Sunday July 27, 2014. He was 85.

Born in New York City in 1928 to Jamaican immigrant parents, Thelma Ione Brooks (neé Delgado) and Owen H. Brooks, Sr., Brooks was raised in Roxbury and lived for a time in Jamaica with his older sister Millicent and the only mother he and his sister knew, his maternal aunt Ceciline L. Barrow (neé Delgado).

He and his mother and sister returned to Townsend Street in Roxbury, and completed his schooling. Brooks graduated from high school at the age of 16, served in the army during the Korean War, studied at Boston and Northeastern universities and eventually completed a program in the rapidly developing electronics industry of the mid-1950s. He was employed for many years as a draftsman specializing in circuitry at the Laboratory for Electronics in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

However, Brooks never felt very enamored of pursuing a career in electronics. Rather, from a very young age, he was more interested in the history of black people and in the politics of their acquiring full freedom and economic independence. At the age of 13, Brooks joined the Youth Council of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. He joined the Progressive Party in 1948 to support Henry Wallace’s campaign for president, read voraciously and attended the lectures and concerts of W. E. B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson.

A small group of mostly black intellectuals in Boston continued their activist work and coalesced around progressive issues that appealed to Brooks’ developing political consciousness. By the beginning of the early ’60s, student lunch-counter sit-ins and freedom rides culminating in the massive white violence those actions precipitated, Brooks knew he must respond with his whole person to the urgency of the Movement’s call.

By 1963, Brooks had committed to local integration efforts, while working to help organize a national support system for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee operating in the Mississippi Delta and in other locations across the South. Brooks met Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer in Boston on fund-raising trips. He marched with Martin Luther King, Jr. for integrated public schools, participated in the March On Washington and grew closer to the organizational links of Movement people and campaigns.

He was particularly drawn to the ongoing work in the Mississippi Delta. Through his longstanding friendship with Warren McKenna, an Episcopal minister in the Boston area, Brooks was recruited to work for the Delta Ministry, an organization of progressive church and laymen and women dedicated to helping poor Black people empower themselves.

Begun in the spring of 1964, DM, as it was often known, was a program established under the auspices of the National Council of Churches’ Division of Church and Society, later known as the Commission on Race and Justice. Brooks joined the staff in the early summer of 1965 and became DM’s director in 1967.

There is no question that in the heat and humidity of the Mississippi Delta, Brooks found himself at home. His political philosophy led him to believe that only in the South, not in the North, could black people realize the potential of their economic and political strength. In spite of a long period of out-migration, Brooks felt that black people’s best hopes lay in how well their numbers — often large majorities in certain Black Belt counties — could work toward their political and economic interests. Putting his shoulder to the wheel, using all his intellectual, material, spiritual and human resources, Brooks pledged himself to work on behalf of the people most in need.

Brooks’ nearly 50 years of experience working in the Delta and around the state, meant that he witnessed and was a part of countless numbers of political and economic initiatives. That experience also meant that he faced violence often, lived through many, many disappointments, if not tragedies, as well as helped strategize important victories. School desegregation in Greenville and other parts of the Delta, the establishment of the Child Development Group of Mississippi and Head Start, as well as the political campaigns to elect the most number of black elected officials of any state were among the victories.

Brooks played a major role in establishing and supporting the work of the Mound Bayou Community Hospital and Health Center. He also assisted Mrs. Hamer’s efforts to establish and sustain a cooperative farming venture in Sunflower County. He was in Atlantic City for the Democratic National Convention in 1964 and again in Chicago in 1968 in order to assist in holding the Democratic Party accountable for the promised changes in party participation.

Brooks marched with King, Kwame Touré and many, many others in the 1966 Meredith March, and was in Selma in 1965. In 1972, he was in Gary, Indiana for the founding meeting of the National Black Political Convention, which was a kind of precursor to the 1984 and 1988 Jesse Jackson presidential campaigns on which he also worked. On these and many other projects, Brooks collaborated with a wide variety of people, politics and egos proving remarkable in his ability to effectively bring people together.

In 1980, Brooks took a one-year hiatus to attend the Community Fellows Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The Community Fellows Program, convened by former Massachusetts state Rep. and friend, Mel King, came under the auspices of the School of Architecture and Planning’s Urban Studies and Planning Department.

Later in his career, Brooks served as field representative to former Congressman Mike Espy from 1987 to 1992. From 1993 to 1995 Brooks served as Congressman Bennie Thompson’s field director. Between 1995 and 1997, Brooks also worked as a field director for the Delta Oral History Project, a collaborative effort between Tougaloo and Dickerson colleges.

In addition, Brooks worked for the city of Jackson in several capacities, including supervisor of the GED Program and employment coordinator with the Department of Human and Cultural Services.

Brooks refused to ever be sidelined from the on-going struggles to achieve social justice. With other movement friends and colleagues, in 2004 Brooks helped found the Veterans of the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement, Inc. He became the organization’s first chairman and served on the Board and as the executive director until his retirement in 2012.

He also served as the organization’s oral historian, traveling the country with digital recording equipment in order not to miss the testimony of another Mississippi vet.

Owen Brooks loved his family and paid special attention to the youngest members. He loved to play poker with the vets, and engage in a good argument just to keep others’ feet to the political fire. He loved music, especially many sacred hymns, freedom songs and the bebop-era jazz of Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk.

Owen H. Brooks is survived by his wife of nineteen years, Mrs. Lescener Harris Brooks, originally from Indianola, Mississippi. Survivors also include his daughters and son Pamela E. Brooks, Frederick Owen Brooks, Angela Y. Brooks-Adams (Terence), and Gail A. C. Brooks. In addition, survivors include Joseph Harris, Leneesa Harris, Millicent Harris and Chauncey Harris. Brooks is predeceased by his daughter Dianne L. Brooks (Robert Kells) and sister Millicent Brooks Broadnax. Nephews Marc Paul Broadnax and Jay Brooks Broadnax survive Brooks as do granddaughters Ronni Brooks Armstead and Deona Brooks, five more granddaughters, three grandsons and one great granddaughter.