Museum of Fine Arts Boston turns focus on Latin America with contemporary art exhibit

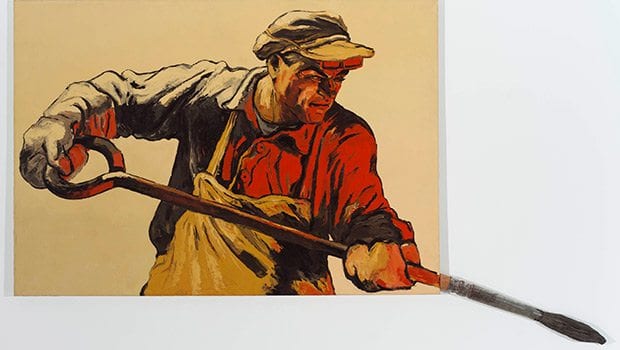

The exhibit “Permission to be Global/Prácticas Globales: Latin American Art from the Ella Fontanals-Cisneros Collection” at Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, features contemporary art from Central and Latin America. This includes “Reja Naranja/Dispositivo Cinético-Social” by Daniel Medina from Venezuela.

Real-world experiences that provoke humor, anger and grief mingle with such art world preoccupations as form, material and aesthetic trends in a bracing exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, “Permission to be Global/Prácticas Globales: Latin American Art from the Ella Fontanals-Cisneros Collection.”

On view through July 13, this joint exhibition of the MFA and the Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation presents 60 works by 46 artists from Central and South America and the Caribbean, including many who reside outside their native countries.

This is the first exhibition focused on contemporary artists of Latin America at the MFA, which aspires to represent all of the Americas — an ambition that drove the museum to create its Art of the Americas wing.

Drawn from the collection of CIFO founder and President Ella Fontanals-Cisneros, the show incorporates sculpture, painting, photography, video, installation and performance art from 1960 to the present by lesser-known artists, as well as A-list figures on the global art circuit.

MFA curators Jen Mergel and Liz Munsell developed this thoughtfully organized show and its bilingual Spanish-English catalog in collaboration with CIFO curator Jesús Fuenmayor. A larger version of the show premiered in December at Art Basel Miami Beach.

In the second half of the 20th century, dictators controlled many countries in South America, seizing power through violent suppression and civil wars. These events shadow many of the works in this show, which distill such experiences through the alchemy of art, transforming humble objects — including chickpeas, inner tubes and a mule hoof — into

Structuralist Study of Poverty by Sergio Vega from Argentina.

evocative images that trigger revelation and reflection.

Among the region’s dictators was Efraín Ríos Montt, who oversaw one of the deadliest periods of Guatemala’s 36-year civil war, which ended in 1996. Despite his brutal track record, he succeeded in securing court approval for his 2003 presidential candidacy.

In response, Argentinean artist Regina José Galindo staged a silent, riveting protest, shown here on a video entitled “Who Can Erase the Traces?” Carrying a basin of blood, she walks from Guatemala City’s constitutional court to the National Palace. Every 10 feet or so, she puts the basin down and dips her feet into the blood, leaving a trail of footsteps to commemorate those slain under Montt’s dictatorship.

Less political but also poignant is an installation by Brazilian José Damasceno, who cut countless pages of old phone books to compose a grove of columns in tawny gold and russet tones. The tree-like figures evoke the passing of lives.

Combining both dark humor and gravity is the video installation by Colombian artist Oscar Muñoz, “Sedimentations” (2011). Enclosed in a darkroom-like chamber, his tabletop projection shows faces submerged under water, as if in a photographic fixing solution, and then wash away to sound of gurgling drain.

The fragility of life and the tragedy of exile are undercurrents of a haunting video by Ana Mendieta (1948-1985), who left Cuba at age 13 and became a successful artist in New York. In “Untitled” (1975), the faint remnant of a childhood photograph shows her posing in a fantastical butterfly costume. The image gradually dissolves into a patch of green that suggests her island homeland.

Next to Mendieta’s video is a humorous tribute to homeland by Magdalena Fernández, whose animated video “1pm00 ‘Ara Ararauna’”(2006) displays a grid in blue, yellow and green, the colors of a macaw, a spectacular native bird of Venezuela. The cool geometric composition mimics a painting by Piet Mondrian. But every few seconds, it shatters with the sound of a macaw’s squawk.

Satire as a form of protest has a rich history in Latin America, ground that the MFA explored in its 2009 exhibition, “Vida y Drama: Modern Mexican Prints.” The show presented works by 20th century Mexican artists who built on their region’s tradition of caricature, a legacy still mined by contemporary artists.

Cuban Wilfredo Prieto’s droll “Untitled (Globe of the World)” (2002) maps all seven continents on a dried chickpea — a dietary staple for millions of people.

Born in Buenos Aires and living in Florida, Sergio Vega spoofs the gap between earnest, elaborate data gathering and the brute reality of poverty in his toy-size diorama, “Structuralist Study of Poverty (Potato, Onion, Garlic)” (2002). Miniature shanties stand on pedestals that resemble bar graphs. Atop each is a basic of rural food production — a potato, an onion and a garlic bulb.

One gallery shows artists recasting the notion of frames and borders. Some are utterly abstract — a ladder leading nowhere, a frame around empty space. But two of the exhibition’s strongest pieces merge aesthetic concerns with substance.

In 1979, while an exile in Brazil during Argentina’s “Dirty War,” Buenos Aires native León Ferrari (1920 – 2013) received confirmation that his son Ariel had been killed by the dictatorship. He then created an elegant, box-shaped sculpture of stainless steel wire, striking in its simple form and delicate interior — an intricate web of interconnecting wires. The structure gains added resonance with its title, “The Cage.”

A resident of both Caracas and London, Daniel Medina embeds social commentary within a handsome specimen of Optical art, “Orange Bars (Social-Kinetic Device)” (2012). Mounted in a corner, the wall sculpture unfolds in three parts. Vertical orange stripes are painted on adjoining walls. Its third element, a hinged metal panel, resembles a security gate — a common sight in upper class zones of Venezuela’s capital city.

Here and elsewhere in this adventurous exhibition, the most memorable works show artists who transcend global art trends to express specifics of life in their world.