Author: Sandra LarsonKarilyn Crockett, center, is flanked by longtime community activists Chuck Turner and Tunney Lee. The three participated in a March 11 forum at RCC on the 1960s fight to stop the extension of I-95 through city neighborhoods.

A recent Roxbury Community College forum brought together a newly-minted Yale doctor in American studies and two elder statesmen of local activism to discuss the victorious 1960s grassroots action to block an eight-lane highway that would have torn through Roxbury, Jamaica Plain, the South End and Cambridge.

Karilyn Crockett, Ph.D., whose 2013 doctoral dissertation “People Before Highways” covers the historic struggle, gave a presentation tracing the community-led fight against the extension of I-95 through city neighborhoods.

“As a person born after the Civil Rights Movement, I didn’t live these stories, but I certainly benefit from them,” Crockett began. The Dorchester native may be best known locally as the founder and long-time director of MYTOWN, or Multicultural Youth Tour of What’s Now, a nonprofit organization that hired and trained public high school students to research local and family histories and lead walking tours of their Boston neighborhoods. Over 15 years, MYTOWN created jobs for more than 300 teenagers. The organization was commended by the National Endowment for the Humanities in 2003 as one of the 10 best youth humanities programs in the nation. Crockett is currently a visiting scholar in urban studies and planning at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

For her dissertation, Crockett spent several years researching the anti-highway movement and interviewing key players, asking what happened, how it became successful and who was involved.

“This story deserves to be told,” she said. “There was a lot at stake for people. It wasn’t just about stopping a highway. It was about making decision-making and governance really reflect the will of the people.”

Though the highway was never built, hundreds of businesses and homes had already been demolished in its proposed path, leaving a wide swath of destruction, especially in Roxbury.

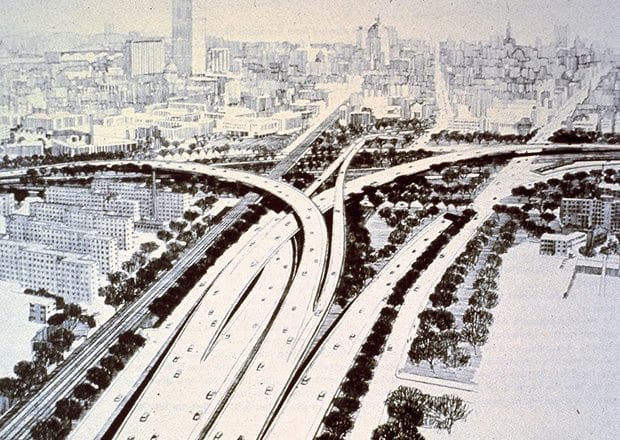

Her slide presentation included maps and photos of the road’s planned route and the land clearance that displaced residents and businesses. She showed a January 1969 gathering of thousands of people at the State House to push then Governor Francis Sargent to stop the plans. Resistance had been bubbling up for some time toward the “monstrous, large-scale project,” but 1969 marked a turn toward greater media and public attention.

Crockett traced three intertwined elements of the era: an urban planning field in crisis that began to question the trend of bypassing urban centers for suburbs; a multitude of 1960s Civil Rights and protest movements; and ordinary residents demanding the right to participate in processes involving their own neighborhoods.

All of these elements played a role in the successful fight, and in 1970, Gov. Sargent finally admitted the plan was wrong. He placed a moratorium on new roads inside Route 128, and by 1972, the I-95 urban extension plans were dead.

A 1973 provision of the Federal-Aid Highway Act (originally called the “Boston Provision” because of its origins in this project) allowed cities to use federal highway funds for public transit and open space projects when new highway plans were successfully opposed. This provision is why we now have an extended MBTA Red Line, new Orange Line/commuter rail tracks and stations, and the Southwest Corridor Park’s gardens, playgrounds and walk/bikeway, she said, though she noted that numerous cleared lots remain vacant, their futures still up for grabs.

A plaque outside the Roxbury Crossing T station honors those who participated in the struggle to protect their city, and she urged audience members to locate and read the plaque.

Crockett’s presentation was followed by responses from Tunney Lee and former Boston City Councilor Chuck Turner, both longtime activists who were players in the anti-highway effort, and whom Crockett interviewed during her research.

Lee, professor emeritus of architecture and urban studies and planning at MIT and an expert in Chinatown history, was part of a group of Cambridge planners in the 1960s who became alarmed at the I-95 plans, questioned their necessity and urged officials to give neighborhoods more power and choice in urban plans.

Lee spoke of parallel stories of neighborhoods victimized by urban renewal efforts, from the hundreds of Roxbury homes and businesses destroyed in the highway’s path, to a Chinatown nearly “swallowed up by Tufts Medical Center” to a demolished West End. Those events also gave rise to some important community-driven successes, including Tent City, Villa Victoria and the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative, he noted.

In 1968, Turner led the Boston Black United Front in demanding a halt to the highway and many other city governance changes. Stopping the highway was an important step, he told the forum audience, but was not sufficient to attain the larger goal of creating a strong and thriving black community. He pointed out that recent development projects along the Southwest Corridor, made possible by the doomed highway plans, include disturbingly expensive apartments, with a market price rent of $1,700 for a one-bedroom unit.

“Political democracy without economic democracy is hypocrisy,” said Turner. “The fight goes on to make America a living economic democracy. It’s a fight that has to continue.”

The March 11 forum was sponsored by the RCC/MIT Associate Campus Partnership Program. In this partnership, international visiting scholars in MIT’s Special Program in Urban and Regional Studies visit RCC to learn about Roxbury history and grassroots organizing, and RCC students have opportunities to connect with urban experts from across the globe and attend lectures on the MIT campus. The forum audience included SPURS Fellows, students in RCC urban economics and social science classes, and Roxbury area community members.

Concluding the program, RCC Associate Dean of Academic Affairs Jose Alicea emphasized that his aim in organizing such events is to showcase victories. While the same community that fought I-95 decades ago still faces acute problems, from violence to unemployment to homelessness, he said, its members can draw on the strength from that success to combat them.

“When people have victories in the past, they can confront problems in the future,” Alicea said. “If we can stop a federal highway through a poor community, we can get together and confront the problems of today.”