For those possessing any insight into the sort of fiction that details the utter bitterness of being young, black and male in a large American city, Johnnie Peterson — the protagonist of Robert Johnson’s play, “Stop and Frisk” is reminiscent of Richard Wright’s character Bigger Thomas in the novel “Native Son.”

As the play begins, main character Johnnie is depicted as an aspiring poet in his early 20s. He is black, poor and fatherless. These hard realities set the stage for his unfortunate collide into the justice system — producing a cautionary tale about white privilege and the advantages possessed by the rich, powerful and protected.

Johnson’s play is an astounding look at the American criminal justice system, giving a cutting perspective to claims that the police and the courts disproportionately abuse the rights of black men through harassment, indiscriminate searching practices and harsh prison sentencing.

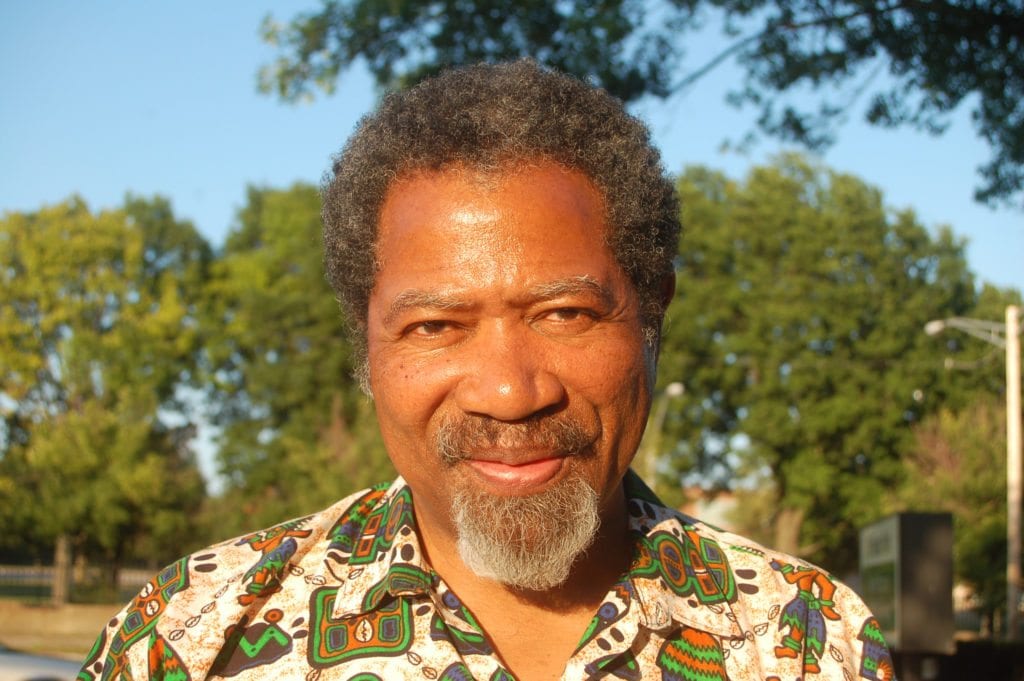

The play — set in Roxbury — will be performed from Feb. 13 at 7:30 pm until March 1 at Boston Center for the Arts, 539 Tremont Street, Boston . Johnson is a professor of Africana Studies at UMass-Boston who has written other noteworthy plays, including “The Train Ride” and “Mama’s Boy,” which was produced at Kenya National Theatre in 1972.

“Stop and Frisk” fictional character Johnnie lives with his mother, Emma, in the Orchard Park projects in the early 1990s — the same run-down projects that Professor Johnson was raised in before leaving for college and earning degrees in law and African studies at Cornell University.

Johnnie’s experiences of facing prison time are cast around Boston history where real life Charles Stuart murdered his white, pregnant wife and blamed the killing on a black man from the Mission Hill projects.

Those events set the city on a racially charged edge, which remains today.

In the play, Johnnie — viewed as a menace to society — is arrested one afternoon by Boston police, charged with assault and battery against the officers and accused of selling crack cocaine to his neighbors.

The ostensible tragedy of Johnnie’s plight is that none of the charges are true. But they stick to him with a frightening tenacity because of Johnnie’s race.

Trying to walk straight, Johnnie is associated only by proximity with friends from his housing project who have sadly waxed cynical — turning to drugs, guns and misogyny.

Mike and Darrell are the two holding crack cocaine when the police descend on them one fall afternoon.

Johnnie’s experiences with the judicial system are searing, forcing — in his mind — a hard-edge realization about how law enforcement can turn sadistic: “They beat us all the time. If you wrote a book about all the brothers around here beat up by the cops for no reason other than being black, you would have a book of stories long enough to stretch from here to the moon. And you know how far the moon is from here?” he says to Copeland, a fellow artist who is also a corporate lawyer.

Indifference to the conditions that young black males confront daily is not only on display by whites in this play. When a black middle-aged judge rules over Johnnie’s legal charges, he shows equal callousness.

Unlike the plight of Bigger Thomas in “Native Son,” relief and realization comes to Johnnie in the end. The recognition of systematic violence comes into clear view.

“Stop and Frisk” possesses a power to convey the icy hopelessness that binds young black men in urban communities.

It is a tale of sound and fury signifying hard-earned revelation.