A troupe of six young actors decides to stage a theatrical presentation — not quite a play — about a little known historical event: the extermination of a tribe in Namibia by the country’s German occupiers.

All they have to go on are letters from a German soldier. How do they bear witness to an event with little testimony other than what is kept by one side, the German occupiers?

This dilemma is central to the play, “We Are Proud to Present a Presentation About the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as Southwest Africa, From the German Sudwestafrika, Between the Years 1884-1915,” a study in articulating the unspeakable.

As its title suggests, the play employs time-honored tools to expose outrage: parody and satire, forms that mingle humor and horror.

A co-production of ArtsEmerson and Company One Theatre, the play is on stage through Feb. 1 at the Emerson/Paramount Center’s Jackie Liebergott Black Box Theatre.

The brick-walled performance space suits the raw, unfinished air of this widely acclaimed play by Jackie Sibblies Drury. Like the Boston production’s director, Company One’s Summer L. Williams, Drury is a young black woman known for fearless, challenging work.

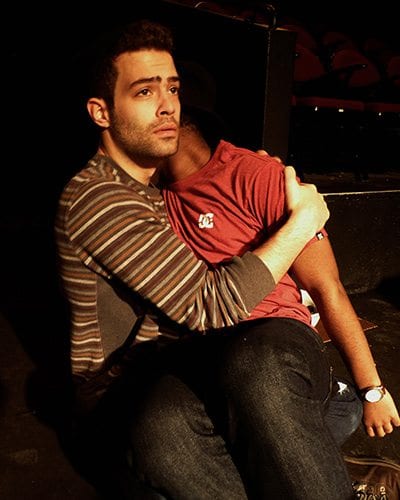

Through a hardworking ensemble of six actors, the production explores both the art of theater and the corrosiveness of power when those who wield it deny the humanity of others.

Scripted and staged as a semi-improvisational performance, its play-within-a-play structure mimics and questions the traditional elements of theater.

But the production’s use of traditional techniques — skillful improvisations, poignant acting, satire — account for its most compelling moments. When the production feigned earnest and sincere directness, denying illusion and blurring the boundaries between acting and life, it lost its edge.

Surrounding the performance space on three sides, audience members face each other as well as the actors.

Set designer Jason Ries has strewn the floor with a few backpacks and cushions and installed an ominous-looking ladder as well as a board showing a crudely drawn timeline of the events in Namibia. Christopher Brusberg’s lighting keeps the space operating-room bright as the actors begin and darkens as their increasingly fraught efforts build to a harrowing finale.

Meredith Magoun’s costumes also echo the play’s transitions, varying from T-shirts and jeans to a hooded cloak that evokes photos of the tortured prisoner at Abu Ghraib.

The performance begins with exciting, unpredictable and fast-moving momentum.

In the role of Actor 6/Black Woman, Elle Borders, a petite powerhouse, introduces herself as “the creative director.” With manic, lightly self-mocking energy, she delivers a wacky, classroom style lecture — “a presentation about the presentation,” complete with a vintage slide projector. Her terrific parody makes the terrible facts all the more chilling.

In 1884, Germany occupied the African country now known as Namibia and quelled the rebellious Herero tribe with brutal suppression and military attacks. The Germans forced the Herero into labor camps, sent them into exile in a harsh desert and ordered the extermination of any Herero remaining in their homeland.

Then the actors prepare to dramatize this harrowing story. Carrying on like seasoned colleagues, they start with a group huddle and a few games to warm up their improvisational skills.

Actor 3/Another White Man, Joseph Kidawski, boasts that he can become the beloved grandmother of Actor 6/Black Woman. Despite his linebacker build, he then melts into the role and she as well as the audience are momentarily spellbound. Their delicate duet demonstrates the transporting, rabbit-out-of-a-hat wonder of acting.

But as the ensemble grapples with their elusive material, the play’s humor dissolves into tension and frustration. “Let’s do this!,” Black Woman commands her fellow actors.

Impressive and never shrill as the ensemble’s dissenting voices were Brandon Green as Actor 2/Black Man and Marc Pierre, Actor 4/Another Black Man. As the group starts reading from the German soldier’s letters and acting out scenes, Green’s character objects, “Where are all the Africans?’’

The actors play roles within roles. As Jesse James Wood — Actor 1/White Man — portrays the soldier, his face shows him slowly waking up to the horror he is bringing to life.

Only one character has a name, Actor 5/Sarah, performed by Lorne Batman. A shadowy figure, Sarah is the wife back home who receives the soldier’s letters.

Blurring the boundaries between group improvisation and an encounter group, this segment of the play went on too long, adding a half-hour to a production billed as 90 minutes with no intermission. Worse, its overindulgence weakened the play’s impact.

After the final scene, the actors survey the audience with searching eyes. They seem to be seeking empathy—a response not earned by the play’s heavy-handed finale.