A comprehensive and effective approach for Boston’s overall economic development requires that discourse about this topic not be limited to the board rooms and meeting places of downtown corporations and elite institutions. Thus, it is impressive that Mayor-elect Marty Walsh has appointed members to his transition teams reflecting the demography — and democracy — of Boston.

The traditional thinking about local economic development is bounded by the notion that if we can help the bigger economic players first, then trickle down benefits are sure to follow. This is an outdated strategy. Through sobering social and economic consequences we know that this strategy has been an utter failure for many of our children and youth and neighborhoods.

There are at least four critical components for enhancing the quality and impact of economic development in ways which moves everyone forward: focused attention on the continuing crisis of poverty and its social and educational manifestations; support for small local businesses and micro-enterprises; support for community-based nonprofits — those organizations on the front lines of our societal safety-nets; and building and strengthening multi-layered linkages between public schools and local communities.

First, a serious and direct anti-poverty strategy is essential for the future well-being of Boston. Boston will never be a Great City — no matter how pretty or sleek the waterfront, or select neighborhoods, might look — if it does not tackle this challenge head on. The observation by Neil Peirce in a Washington Post column (Aug 15, 2008) is still most relevant: “Poverty places a huge drag on the economic output and productivity of states and communities…those who spend their first five years in poverty will face daunting odds — first lagging school performance and then as adults, 40 percent less income, 70 percent more poor health conditions … small wonder that by some estimates, childhood poverty is draining a massive $500 billion a year out of the U.S. economy.”

The latest American Community Survey census reports that close to one-fifth of all persons living in Boston are officially impoverished; for black and Latino persons and families the figure is much, much, higher.

A second key component for comprehensive and equitable economic development includes focus on the well-being of our smaller, local neighborhood-based businesses.

It is interesting that in 2009 approximately 2,400 businesses were counted by InfoUSA in some of Boston’s poorest neighborhoods of Roxbury, Mattapan and Dorchester. More than half of these businesses — about 1,600 — employed between one and four workers; another 400 or so, employed between five and nine workers. While individually small in terms of employees, the workforce represented by this sector totals thousands of employees; local businesses in our neighborhoods also help to generate hundreds of millions of dollars in disposable income.

Furthermore, local businesses, including micro-enterprises, represent an integral part of a neighborhood’s social infrastructure. They tend to reflect the racial and ethnic, and linguistic, diversity of residents of the city to a far greater extent than the much bigger corporations and institutions.

A third key for effective local economic development is supporting and enhancing the capacity of community-based nonprofits. This sector is on the front lines of helping people and children. Many community-based nonprofits have been left to swim on their own under a “survival of the fittest” mentality that ignores the key contributions and role that this sector has played and can continue to play in some of the most vulnerable areas of the city. Not working with this sector to expand its capacity, especially in working-class, low-income and communities of color means, ultimately, that the problems they are trying to address will get worse.

A fourth component of comprehensive economic development should involve the deepening of partnerships among parents, students and schools, and community. Our economic future is directly linked to the quality of public education, of course. This is precisely why we need to move from being satisfied with “pockets of excellence” to community-wide academic achievement.

There are a lot of good ideas for improving our public schools. But simply calling for more charter schools as panacea, or highlighting how this one school or two schools passed the high stakes testing screens, or blaming teachers, all miss the boat of the future. The discourse on education reform and how to improve the quality of public schools has been silo-ed with piecemeal reforms that can be disconnected from a bigger picture, including what might be in the best economic development interests for Boston.

An overall economic development strategy which does not pay adequate attention to some of these missing links in traditional economic development — the challenge of poverty; the significance of small and neighborhood businesses; the critical role of our community-based nonprofits and utilizing public schools as venue for partnering with neighborhoods — does not reflect smart economic development for the future of Boston.

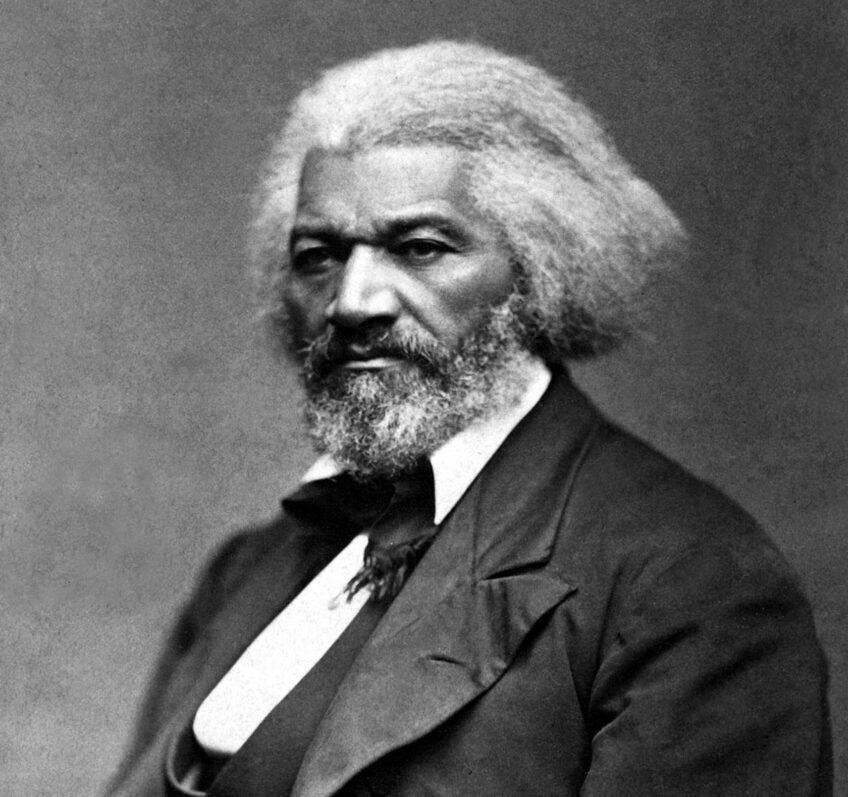

James Jennings, Ph.D., is professor of urban and environmental policy and planning at Tufts University.