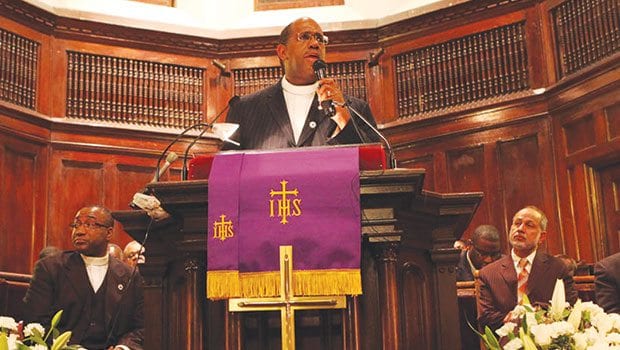

Rev. Gregory S. Groover admits to misusing $850,000 in grants to pay for expenses at Charles Street African Methodist Episcopal Church

Saying he was “wrong,” Rev. Gregory S. Groover Sr. admitted on the first day of his church’s bankruptcy trial that he used $850,000 in restricted grant money to pay for day-to-day expenses at the historic Charles Street AME church over the last five years.

Groover’s startling testimony underscored the pattern of financial mismanagement that has been revealed over the last year of motions, depositions and hearings before U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Frank Bailey.

At issue is whether the court will accept the church’s proposed plan to repay nearly $5.2 million in loans to OneUnited bank, the nation’s largest black-owned bank, as well as additional funds to outstanding creditors.

Charles Street attorneys have argued that once the bankruptcy hearings are completed, the church can then finish building its Roxbury Renaissance Center and start generating money by holding weddings receptions and community meetings to repay its debts over a 30-year period.

OneUnited attorneys have opposed such repayment plans in large part because of what they have discovered are significant problems with the church’s financial statements that are being used to determine the repayment plan.

Those financial statements, coupled with the testimonies of Rev. Groover Sr. and Rev. Opal Adams, the woman who kept the financial books and authored Groover’s annual reports, demonstrate what bank attorneys characterized as “a false portrayal of its financial circumstances and purposefully [overlooking] its obligations.”

At the center of the Charles Street AME Church bankruptcy hearing is the uncompleted Renaissance Building.

The litany of financial problems goes on and on, the most recent involving the use of Lilly Foundation funds which were designated for use only to support the church’s pastoral program.

Since 2003, Charles Street has received nearly $3 million in grants from Lilly to run a pastor in residence program.

But on Monday, Groover explained after a thorough review of the church’s financial records, they improperly transferred $850,000 from the Lilly funds to pay for expenses.

In 2007, Groover said, without telling senior members of the church or the congregation, he transferred $145,000 for “other purposes.” In 2008, the amount was $163,000. In 2009, $80,000 was used; in 2010 $162,000; in 2011, $194,000; and in 2012, $147,000.

Groover insisted that he was only “borrowing” the money and had every intention of repaying “every cent.” When asked who authorized such transfers, Groover said, “I did” and then explained that the money was used to pay for “pressing obligations,” including repaying OneUnited as well as for construction related expenses.

Groover testified on Monday that he wrote a letter to the Lilly Foundation earlier this year to explain “his mistakes” in the use of their grant money. Groover said Lilly officials were “disappointed” and that he had “violated the spirit” of the grants. But Groover testified that a high-ranking Lilly official told him that they had “every confidence” that he would repay the money in full.

The relationship between OneUnited and Charles Street started on Oct. 3, 2006, when Groover agreed to borrow $3.6 million to build a 22,000-square-foot community center on church-owned land near Grove Hall, featuring a grand ballroom, multi-purpose meeting space, conference rooms, prayer and meditation space and sound proof musical practice rooms.

The OneUnited construction loan became due on June 1, 2008, and despite a total of five extensions, the church was unable to satisfy its debt by Sept. 1, 2009. A year later, on Aug. 17, 2010, OneUnited then sued in Suffolk Superior Court for breach of contract.

Also named in the suit was Charles Street AME’s co-signer, the First Episcopal District of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, based in Philadelphia. At the time, the First District, based in Philadelphia, claimed it had $65 million in cash and nearly $500 million in assets, and had pledged its assets as collateral for the loan.

Charles Street had also borrowed another $1.1 million, separate from the $3.6 million construction loan. That loan is also in default.

To forestall the pending foreclosure of its property by OneUnited Bank, Charles Street filed for bankruptcy in March 2012 in a move to keep the church operating as it has for nearly the last two centuries. In addition to its debts to OneUnited, Charles Street owes about $630,000 to Thomas Construction Co., the Dorchester firm hired to build its proposed community center; another $450,000 is owed to Tremont Credit Union for a loan to repair the church’s roof.

Groover now says the church is “upgrading its financial management” by creating a new “atmosphere of transparency,” keeping better financial records and ending the church’s policy of cash withdrawals from church bank accounts.

Groover also testified that the he has cut expenses at the church and pointed out that he had not received a raise in his salary of $70,000 since 1998.

In documents filed last year, OneUnited bank rejected a repayment plan offered by Charles Street to repay its outstanding loans — a payment plan of $27,000 a month over the next 30 years.

Based on financial statements submitted by Charles Street, OneUnited attorneys remain unconvinced that the church would make such payments. Charles Street even asserted as much.

“Our operations,” Charles Street financial documents state, “are dependent on individual donations for substantially all of our revenues, and there is no guarantee that donations made from such sources will remain at levels comparable to present levels or that they will be sufficient to cover all operating and fixed costs.”

In fact, the church argued, “increased unemployment or other adverse economic conditions in our community might decrease our congregation’s ability to contribute to the church.” According to the proposed Charles Street plan, none of the smaller creditors — the 28 companies owed amounts ranging from $370.18 to $17,790.88 for a total of about $115,000 — would receive any money.

But the plan would pay Thomas Construction. That money, targeted to repay an outstanding $250,000 to the construction company and “complete” the project, would come from what Charles Street described as “generous assistance” from the First District — a $1.5 million “donation.”

In court documents, OneUnited lawyers described the Charles Street plan as “disgraceful” and called its financial management “a failure.”