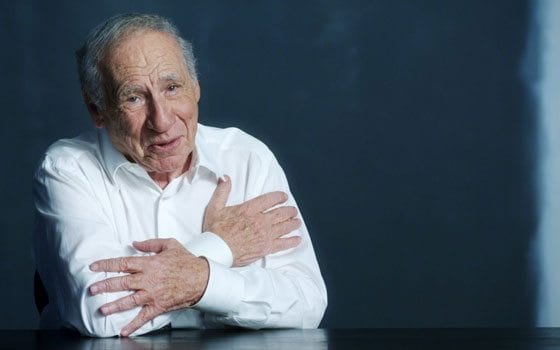

Mel Brooks — director, producer, writer and actor — is in an elite group as one of the few entertainers to earn all four major entertainment prizes — the Tony, Emmy, Grammy and Oscar. His career began in television writing for “Your Show of Shows” and together with Buck Henry creating the long-running TV series “Get Smart.”

He then teamed up with Carl Reiner to write and perform the Grammy-winning “2000 Year Old Man” comedy albums and books. Mel won his first Oscar in 1964 for writing and narrating the animated short “The Critic,” and his second for the screenplay of his first feature film, “The Producers,” in 1968.

Many hit comedies followed, including “Blazing Saddles,” “Young Frankenstein,” “Silent Movie,” “High Anxiety,” “Spaceballs,” “Life Stinks” and “Robin Hood: Men in Tights.”

From 1997-1999, Brooks won Emmy Awards for his role as “Uncle Phil” on the hit sitcom “Mad About You.” Brooks received three 2001 Tony Awards and two Grammy Awards for “The Producers: The New Mel Brooks Musical,” which ran on Broadway from 2001 to 2006.

“The Producers” still holds the record for the most Tony Awards ever won by a Broadway musical.

In 2009, Brooks received The Kennedy Center Honors, recognizing a lifetime of extraordinary contributions to American culture. His most recent projects include the Emmy-nominated HBO comedy special “Mel Brooks and Dick Cavett Together Again” and a career retrospective DVD box set titled “The Incredible Mel Brooks: An Irresistible Collection Of Unhinged Comedy.”

Here, he talks about “Mel Brooks: Make a Noise,” an American Masters profile chronicling his illustrious career. The PBS show premiered nationwide on Monday. And in June, Brooks will be honored with a Lifetime Achievement Award by the American Film Institute (AFI) at a gala tribute airing on TNT.

Hello, Mr. Brooks. I’m honored to have this opportunity to speak with you.

Thank you, Kam. Hey, what the hell is Kam short for?

It’s short for Kamau, an African name.

I’m so sorry to hear that. I thought it might be short for my last name, Kaminsky. I was hoping you just took my last name and shortened it to become part of the family.

[Chuckles] No, I took the name back in the ‘70s during my brief career as a jazz musician. You started out as a jazz musician, too, right?

I did, I did. We were both jazz musicians, so it’s like we already know each other. In the early ‘40s, before I went off to World War II, I was in a little five-piece group that played at those Borscht Belt resorts in the Catskill Mountains. One night, the comic at the Butler Lodge got sick, and his boss, Pincus Cohen, begged me to perform in his place. I told him, “That name is redundant. Pincus and Cohen, you don’t need ‘em both. We know you’re a Jew.” [Laughs] He said, “I’ve watched you doing rehearsals. I can tell you’re a funny guy.” I knew all those dopey jokes, so I went up on stage, and that’s how I got into comedy. I was only about 15 at the time.

What was the hardest film to shoot because of laughter breaking out on the set?

“Blazing Saddles” was pretty damn funny. The crew was constantly cracking up and ruining takes. So, finally, I sent my assistant to Woolworths to buy a thousand white handkerchiefs. I gave one to everybody on the set. I told them, “If you feel like laughing at something, you stick one of these in your mouth, bite on it and laugh through it.”

Anytime I wasn’t sure whether a scene was working or not, I’d look over my shoulder, and if I saw a lot of white handkerchiefs, I’d know it was funny. That became my litmus test. The crew’s laughing could’ve ruined the picture, but we saved it with the white handkerchiefs. It also turned out to be a great way to test to see if something was funny.

Why do you think “Blazing Saddles” remains as fresh as ever?

What makes it last so long is that there’s a black sheriff that everyone in that world of 1874 wants to see dead right away. But he endures and gains the respect of the townsfolk, especially the Waco Kid [played by Gene Wilder]. That’s the engine that drives it, and that’s why it’s still around. It’s around because there’s a tremendous amount of focused emotion in that movie.

When I interviewed Quentin Tarantino about “Django Unchained,” he attributed the demise of the Western to “Blazing Saddles.” He said that you had parodied the genre so effectively that no one could take them seriously anymore.

[Laughs] I don’t know. Maybe he’s right. But I wouldn’t take credit for that.

One of my favorite comedies is “Young Frankenstein.” The casting was sheer inspiration. What could you tell us about your collaboration with Gene Wilder? With such a brilliant cast, was it a collaborative effort, or primarily carved out by you and Wilder?

It actually came from Gene Wilder’s head. One day when we broke for lunch out in the desert during the shooting of Blazing Saddles, I saw him scribbling on a legal pad and on the top it says “Young Frankenstein.” And I said, “What the hell is that? What’re you doing?” And he explained to me his idea and asked me if I’d collaborate with him on it. I said, “Sure.” As far as the casting, there was a guy named Mike Medavoy who had in his stable of actors Gene Wilder, Peter Boyle and Marty Feldman. The only ones he didn’t have were Madeline Kahn and Teri Garr.

For better or worse, how do you see comedy changing on the screen over the past half-century?

That’s a good question. I wish I could answer it. Comedy is too vast a subject. I don’t know what it is. It’s reaching a place in us that is unrestrained. That place where we can no longer be a proper part of society, and just have to laugh. If you have the ability to reach it in yourself, you’ll reach it in others. But how it’s changed, I don’t know. All the sitcoms have gotten very sexual, but not necessarily funnier.