It was called “the New Bedford Annex for Boston Radicals,” and at the dawn of the 20th century, the well-appointed house on Arnold Street was one lively place.

Owned by African American lawyer Edwin Bush Jourdain, the house in the West End section of New Bedford saw the likes of W.E.B. Du Bois and William Monroe Trotter debating strategies that challenged the accommodationist policies of Booker T. Washington.

To this day, Jourdain’s descendants confirm that at one time their ancestor’s house had been frequented by the black intelligentsia, who exchanged ideas, rehearsed speeches and executed plans for curing the ills facing black Americans.

Jourdain was a prominent member of a thriving community of color that had been living in New Bedford for decades. His middle-class status and education were nothing new to this community. Coming from a long line of established small businessmen, Jourdain was the nephew of Andrew Bush, who founded Bush Cleaners in 1885.

After graduating from the Boston University School of Law in 1888, Jourdain opened law offices on William Street, just across from New Bedford’s Custom House, still the nation’s oldest continuously operating custom house. Jourdain balanced a legal career with an ever-growing public career.

It wasn’t long before Jourdain found himself among a steadily growing circle of black professionals and equal rights activists in residence or in council in New Bedford. By 1900, his Arnold Street house had become a critical gathering place for the black intellectual elite of the Northeast.

“Boston Radicals”

Born between 1855 and 1875, this generation of so-called “radicals” came up against unrelenting barriers and obstructions based on race.

Nonetheless, by accident of birth or by personal meritocracy, many of these radicals had life-altering experiences. Travels abroad, entry into prestigious schools and exposure to unexpected resources were advantages many in these circles had that other blacks did not enjoy.

Such advantages made these circles conspicuous, but it also obliged them to network and congregate with one another. They soon became representative leaders for a segment of America’s population that desperately needed agendas for public policy and political action.

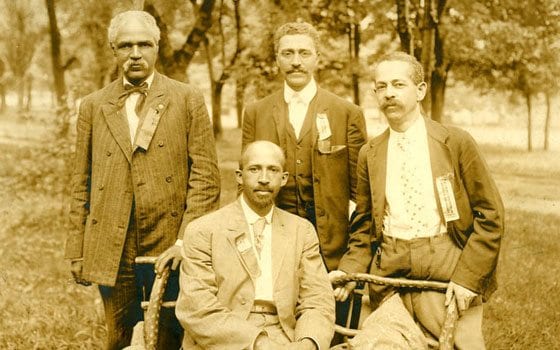

By the turn of the 20th century, these circles were participating in and witnessing the birth of grassroots civil rights meetings and organizations in black America. One of the more famous of these gatherings took place in Niagara Falls, Canada, in 1905.

It was not by chance that E.B. Jourdain was one of the “original twenty-nine” who attended the first meeting of what became known as the “Niagara Movement.” In fact, he was typical of these original founding members who were often politically motivated and unabashedly opinionated when it came to the topic of equal rights for African Americans.

Jourdain and his guests debated the issues of their day in the seclusion of the New Bedford Annex. Back then the list of problems was extensive, and cloaked under concepts such as “separate but equal” or “Jim Crow.”

But it was clear where Jourdain stood on the equal rights issue. According to prominent historian Louis Harlan, Jourdain admired the work of Booker T. Washington at Tuskegee, but was critical of Washington’s conservative public utterances and his failure to be more outspoken on matters of civil rights.

“We respect Mr. Washington’s devotion to the educational interests of his race; we admire his genius in rearing such a beacon light as Tuskegee, in the dismal swamp of ignorance and degradation, the great black belt,” Jourdain wrote one of Washington’s confidantes on Aug. 19, 1902. “But we cannot follow his lead when he counsels ‘nolo contendere’ in the matter of manhood and citizenship rights.”

Jourdain went on to describe the situation in New Bedford, where some residents understood fully the value of “material advancement.”

“… For while we number only about 1,700, we pay taxes on real estate the assessed valuation of which is about $330,000.00; and our percentage of men in business for themselves averages well with other races,” Jourdain wrote.

But as Jourdain rightly pointed out, industrial training and high moral values were only part of the solution.

“Love of personal history, a jealous defense of their rights and liberties have been the dominant traits of every people who ever achieved anything admirable, and we believe those traits to be prime essentials of the Negro American today,” Jourdain wrote.

New Bedford: The host city

In spite of its size, when it came to meeting places for the black elite, New Bedford was in the company of cities like Boston, Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, Atlanta and New York City.

The roster of Niagarites that either frequented Arnold Street, or knew of it, expanded to include Mr. and Mrs. Clement G. Morgan of Boston; Archibald Grimke of Boston; Dr. Rebecca Cole, a physician and graduate of the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania; and Mrs. Ida Gibbs Hunt, a graduate of Oberlin College.

The male-dominated Niagara Movement charged men a $5 fee for full membership and a $1 associate membership fee for women. Nonetheless, the membership anxiously listened to the platforms and campaigns of men such as W.E.B. Du Bois, William Monroe Trotter and Booker T. Washington.

Washington included New Bedford on his national lecture tour. He traveled with a secretary and aides who meticulously recorded the impact of manual skills, apprenticeship and personal initiative training in black communities up and down the East Coast. Perhaps to a fault, Washington was overly optimistic about the future of black enterprise and its place in America’s free marketplace.

As early as 1895, Washington had speaking engagements in New Bedford churches such as United Pilgrim Methodist Church and the New Bedford Unitarian Church. The college he founded, the Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, Ala., received philosophical and financial support from wealthy philanthropist Warren Delano III, a nephew of Franklin D. Roosevelt and resident of Fairhaven, Mass., just across the Acushnet River from New Bedford.

In addition to Washington, Du Bois, a born and bred Massachusetts resident, was also making a name for himself as a candid, often opinionated intellectual with academic credentials that included Fisk and Harvard universities, as well as extended study at the University of Berlin and the University of Paris.

Like Jourdain, Du Bois was one of the “original twenty-nine” organizers who met in Niagara Falls, Canada, in 1905. He frequented Jourdain’s Arnold Street residence and was known to draft speeches, position papers and essays during visits.

Du Bois had a very personal connection to New Bedford. His grandfather, Alexander Du Bois, had been a resident of New Bedford since 1873.