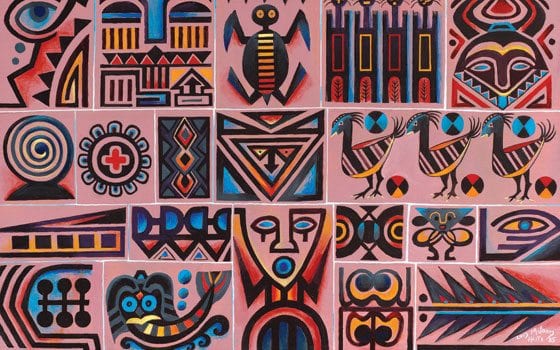

Author: MFALoïs Mailou Jones’ “Glyphs,” a 1985 acrylic on canvas on display at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Author: MFALoïs Mailou Jones’ “Glyphs,” a 1985 acrylic on canvas on display at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Born and raised in Boston, Loïs Mailou Jones (1905 – 1998) overcame obstacles she faced as a woman and an African American to become an artist recognized as an individual rather than an exemplar of her gender or race. During her distinguished 70-year career, Jones created a body of work that ceaselessly incorporated what she learned and experienced along the way.

Her paintings draw the eye with their warm colors, strong design elements and African American motifs. Although some would look at home in a show with early 20th century Modernists, her paintings are seldom entirely abstract. You can detect the presence of the artist and her lived experience.

Building from her classical education in the fine arts at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where she majored in textile design and graduated with honors in 1927, Jones wove the myriad threads of her teaching and art-making into a rich and unique body of work.

“Being basically a designer,” Jones said to fellow African American artist Romare Bearden, “I am always weaving together my research and my feelings — taking from textiles, carvings, and color — to press on canvas what I see and feel. As a painter, I am very dependent on design.”

A compact and alluring survey of her art and life entitled “Loïs Mailou Jones,” is on view at the Museum Of Fine Arts, Boston, through Oct. 14, 2013. Installed in the Bernard and Barbara Stern Shapiro Gallery on the second floor of the Art of the Americas Wing, the mini-retrospective presents nearly 30 works in various media and styles. The show presents the MFA’s entire collection of 21 paintings and drawings and illustrated books, as well as her illustrated books and works on paper lent by the Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists in Roxbury.

“Jones is a major 20th century artist,” says Elliot Bostwick Davis, John Moors Cabot Chair of the Art of the Americas Department. “This mini-retrospective gives a sense of her career unfolding, her muses and what it takes to develop a voice.”

Jones regarded the MFA as her home, notes Davis. In 2005 and 2006, Jones bequeathed eight paintings and eight works on paper to the MFA through the Loïs Mailou Jones/Pierre-Noël Trust and established a scholarship at the Museum School. The artist’s bequest has been a catalyst, observes Davis, who oversaw the recent expansion of the MFA’s works by African American artists to nearly 450 objects, among the largest such holdings by any museum in the U.S.

Jones was encouraged to achieve by her parents, Carolyn Dorinda Adams Jones, a cosmetologist and milliner, and Thomas Vreeland Jones, the first African American graduate of Suffolk Law School. Jones found mentors both at the MFA and among the African American intellectuals who frequented Martha’s Vineyard, where her family had a summer home.

Driven to make a name for herself, Jones turned obstacles into opportunities.

Well into her first year as a successful freelance textile designer, Jones spotted her work on display in an interior decorator’s shop. When she introduced herself as the artist, the proprietor said, “How could you have done that? You’re a colored girl.”

Not only stung, Jones also felt thwarted by the anonymity of textile design. She turned to painting and to support herself, applied for a teaching post at her alma mater. Its director, Henry Hunt Clark, advised her to instead go South and “help her people.”

Jones decided that moving ahead meant moving away. Soon after she began teaching fine arts at Palmer Memorial Institute in Sedalia, N.C., she was recruited by Howard University in Washington, D.C. In 1930, she joined its art department faculty. Almost three decades later, in 1977, she retired as an honored professor emerita.

“Howard was a crucible for her,” says Davis. “She met the foremost African American intellectuals of the era. Her colleagues were leading lights of the Harlem Renaissance.”

They included African American intellectuals such as Alain Locke, known as the father of the Harlem Renaissance, who urged Jones to bring her African heritage into her work.

Perhaps in response, in 1932, Jones created one of her greatest paintings, “The Ascent of Ethiopia” (not on view), which unleashed a visual vocabulary she would return to in later years. A surging Afro-American rhapsody in blue, black and gold, the strongly geometric composition integrates images of Africa — a mask-like profile of a pharaoh and pyramids — with the silhouettes of skyscrapers and a jazz combo.

Photos of Jones at various stages of her life accompany introductions to the four sections of the exhibition: her refined copies of MFA works as a student; her teaching career at Howard; her 1937 sabbatical in Paris and later travels to Haiti and Africa. The section on her teaching career displays a variety of works on paper, including commanding charcoal portraits of her young students.

Among her Howard colleagues was the pioneering African American historian Carter Godwin Woodson, who founded The Associated Publishers, Inc. Jones illustrated its children’s history and literature books, which cast African Americans as protagonists, encouraging racial pride.

Her exquisite pen and ink drawing for Gertrude Parthenia McBrown’s poem “The Paint Pot Fairy,” shows a dainty fairy with an Afro painting autumn leaves.

A life-changing sabbatical year at the Académie Julian in Paris in 1937 is the subject of the show’s third section. In Paris, Jones felt “shackle free.” She was inspired by the sensational African American dancer Josephine Baker and captivated by the Impressionist paintings of Mary Cassatt and Edgar Degas as well as Post-Impressionist works of Paul Cézanne and Émile Bernard.

While in Paris, Jones formed a lifelong friendship with fellow art student Céline Tabary, who later helped Jones win a prestigious award from the Corcoran Gallery of Art by submitting a work by Jones as her white surrogate. In 1994, the Corcoran hosted a birthday party in honor of Jones to open its exhibition, “The World of Loïs Mailou Jones,” and made a public apology for its past racist policies.

The influence of Degas is visible in the oil painting “My Mother’s Hats” (1943), but so are stylistic elements true of her later work: an interplay of rectangles and ovals, strong oranges and reds, and a richly textured surface that crackles with energy.

Contemplative but animated, her watercolor and pencil drawing, “Portrait of Céline Tabary” (1940) is a luminous rendering that frames Tabary’s delicate face with her jaunty hat, wide lapels and the paintings behind her.

The exhibition’s fourth section, entitled “Further Travels,” shows how visits to Haiti and Africa transformed Jones’s paintings, injecting bolder color and a return to pared-down, sculpted forms.

In 1953, Jones married Haitian graphic artist Louis Vergniaud Pierre-Noël and together, they often frequented the island. She absorbed its lively palette and its spiritual icons rooted in Africa. In 1970, traveling on a Howard research grant, Jones made the first of four trips to Africa. Like so many other Western artists in the 20th century, Jones drew from its masks, sculptured forms and cultural symbols.

In her most abstract painting on view, “Glyphs” (1985), based on African hieroglyphics, striped birds with saucy tail feathers are kindred in spirit to Josephine Baker’s costumes.

Her acrylic and collage tribute “La Baker” (1977) reigns in the gallery. The riveting image sets Baker, her fellow pioneer, within her own self-made iconography as well as African and Afro-American imagery. Delicate tufts of handmade paper evoke the dancer’s jaunty feathered skirts. The sleek, minimalist rendering of her body, in brown and white, conveys unbridled joy that transcends race.

Another of the show’s most arresting works is the latest on view, an illustration from her 1996 collaboration with the first president of Senegal, “The Poems of Léopold Sedar with Silkscreens by Loïs Mailou Jones.” Displayed in a glass case, the large book is open to his poem, “À New York,” an ode to the city’s verve. Like heirs of Baker, chorines in white feather headdresses and tutus move to a jazz band. Jones surrounds her ebony figures of dancers and musicians with a fuchsia backdrop with a green palm tree.

The composition is an angular convergence of line and color brimming with life. Here was Jones, at age 91, two years before her death, still experimenting, and still rendering the richness of her colorful life.

LECTURE: Loïs Mailou Jones as Pioneer and Friend

Wednesday, Feb. 20, 7 p.m.

Remis Auditorium, Museum of Fine Arts, 465 Huntington Ave., Boston

Tickets: $10 for members, seniors, students; $13 for non-members

Edmund Barry Gaither, Director of the Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists in Boston, in a conversation with exhibition curator Elliot Bostwick Davis, will reflect on his friendship with Jones and discuss her role as a pioneering 20th-century artist and teacher. Gaither and Davis will expand the discussion to the artist’s place in the broader context of American art, exploring how her style influenced many during the Harlem Renaissance and beyond.