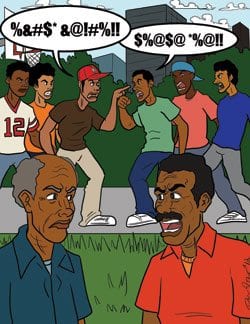

Several generations ago it was customary for African American adults to greet one another with respectful formality. That practice created a spirit of self-confidence even though bigots addressed blacks with blatant disrespect.

The natural etiquette that sustained the camaraderie of the community has devolved over the years into a vulgar informality that often fails to acknowledge another’s humanity. As a result, many people have lost the support from others for their self-respect and even their human dignity.

As cultural mores have changed, African Americans do not see the decline of their own values. Perhaps it will be helpful to assess a political conflict in another community to understand what could happen subtly closer to home.

A political battle is now raging in Selma, Ala. over whether a new monument to Nathan Bedford Forrest should be constructed in the city’s Live Oak Cemetery. State Sen. Hank Sanders, an alumnus of Harvard Law School, is leading the opposition. Surprisingly, some blacks are on the other side.

Forrest was a Civil War general who commanded the massacre of hundreds of prisoners of war who were black or white southerners who had joined the Union army. A native of Tennessee, Forrest led the Confederate troops defending Selma.

After the war, Forrest became the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. It was that function that endeared him to the segregationists. Sanders asserts that it is white supremacy to support raising “… a monument on public property in honor of one who killed black women and children, killed black Union soldiers who had surrendered and the white officers who led them, and after the war built the Ku Klux Klan into a force that attacked, terrorized and murdered black people for a hundred years, it is just freedom of speech. It is preserving their culture. It is recognizing their history.”

Forrest’s career is infamous and he is unworthy of any special recognition anywhere, especially in Selma, whose population is now 66.4 percent black. Selma became famous on March 7, 1965 with the police attack on the march of freedom fighters over the Edmund Pettus Bridge. It is singularly inappropriate for a monument to Forrest to be established there.

Sanders objects to the white criticism of his opposition. He declared, “When those whose forbears were attacked, terrorized and murdered protest such a monument, it is rabble rousing, hurting the city, destructive to the image of the city and not at all freedom of speech.” He identifies that attitude as white supremacy.

Strangely enough, according to Sanders “some black people do not see anything wrong with the monument to Nathan Bedford Forrest. We are so used to symbols of our own oppression that we cannot see the damage to ourselves and our children. Moreover, we see no harm in following an admitted disciple of Nathan Bedford Forrest and proud white supremacist. That’s … black inferiority forged by white supremacy.”

Acceptance of a monument to a racial oppressor is not the only symptom of black inferiority and the slave mentality. Far more damaging is the failure of blacks to treat one another with respect and courtesy. This indignity often leads to the hostility and violence that plagues urban neighborhoods.

A major task of African Americans is to supplant the sense of inferiority created by white supremacy with a spirit of self-confidence that will enable and inspire a high level of achievement.