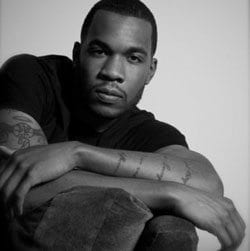

Chicago-born, Boston-bred director Jae Williams is flipping the script.

A product of the hip hop generation, the Emerson College film school grad came of age in an era when the excitement of movies and visual media that explored new aspects of the black experience eventually gave way to exploitative portrayals of African American life and culture.

“Growing up in the late ’80s and ’90s, when “Boyz N the Hood” and “Higher Learning” and “Menace II Society” and all those films came out… [they] highlighted or glorified an athlete or drug dealer,” Williams says. “That was the only way to become successful — at least that was what was depicted in those movies. We kind of got used to that.”

Since then, young African American filmmakers like Williams have struggled to bring new visions of African American life to the silver screen and have their work accepted by audiences.

“It’s tough,” he says, noting last year’s brief war of words between critically-acclaimed director Spike Lee and the Christian-leaning, blockbuster media monolith Tyler Perry. “Sometimes, I feel that we get pigeonholed into one genre. It’s either a Spike Lee movie or a Tyler Perry movie.

“I think we’ve been conditioned to think that’s all Hollywood is going to accept; they’ve filled their quota,” Williams says. “It encourages a lot of young African American filmmakers to copycat what’s already been done, and it limits the creativity and the types of films that come out.”

But rather than simply depicting the depravities of black life or glossing over them altogether, Williams’ films rewrite those stories, using subtle yet powerful characters to examine how society cultivates the experiences that cause people of color to hurt.

“I want to be able to explore gritty urban issues without the violence, without [making] the stereotypical sexual, drug-related, gang-related film,” he explains. “Although there are elements of that in film and life, there are other avenues that you can take to [explore those elements].

“I want to create characters who have this urban, sort of ‘real’ lifestyle, but give them charisma, give them academic success, and not just [have them be] an athlete or drug dealer, things we normally see growing up, especially growing up in the past 20 years or so. I definitely want to go against the grain in doing that.”

Williams seems to have no problem choosing the road less traveled, and picking and sticking to his own path has proven fruitful. His short film “Listen,” which was screened for the first time at this year’s Roxbury International Film Festival, earned him the Kay Bourne Emerging Filmmaker Award.

“Listen” puts viewers face-to-face with Saniya, a young mother suffering from post-partum depression. Played out in a series of flashbacks, monologues and extreme close-ups, the film is unsettling even from its first scenes. As the camera zooms in on Saniya’s eyes and face, viewers get a glimpse into a tortured soul whose perception of her parents’ taboo interracial relationship has influenced her thoughts and behaviors.

When Saniya reveals the harrowing act of desperation that will change her life forever, the moral of the story, the point of it all, comes into focus — racism and broken homes push many people of color to seek refuge in reckless behavior.

“Listen” demonstrates Williams’ thoughtful approach to crafting message-oriented movies that are as attractive to the eye as they are stimulating to the mind.

“My favorite part of creating the visual is really finding an issue and creating a concept and sticking to it,” he says. “I’m forced to be creative.”

“On the surface, post-partum depression is boring and depressing in and of itself,” he adds. “I think that’s where the challenge is for me. How do I take this concept, how do I take this issue and create a story around it that’s going to be compelling enough to where someone’s going to pay attention and learn something from it?”

Like many filmmakers, Williams is convinced that seeing is believing: Watching things develop or unfold with images deepens our understanding.

“It’s in our nature to visualize,” he says. “Anytime anyone tells you a story, you always sort of picture it in your head how it actually went down. And that gives [the story] more substance and value.

“When you entertain through television or film or music, people tend to have a conversation about it,” he says. “When you’re discussing how you felt about a particular song or movie or TV show with your spouse or your co-worker, that’s really when the ideas begin to spread. That’s when you really begin to make an impact.”

As he moves forward with screening his newest short, “La Armonia” and producing a feature length film titled “Forever Ink,” developing dialogue both on and off the page and screen continues to be his mission and mantra.

“If I can create conversation where someone feels comfortable talking about an issue such as post-partum depression or illiteracy, then I think that’s where I can leave my mark.”