Olivia Hamilton was pregnant and in prison. Serving a one-year sentence for stealing money from work to pay her bills — about $700 — the New Orleans resident was just three months shy of her due date when she was put behind bars.When her due date finally arrived, she was taken to a hospital, chained to an operating table and given a medically unnecessary c-section against her will.

“I think my medical treatment in prison was cruel, degrading, and shameful,” Hamilton said. “Being shackled, being forced to have that C-section — it was the worst feeling, mentally and emotionally, that I have ever been through.”

Less than 48 hours after her baby boy was born, he was taken from Hamilton. “Walking out of that hospital, knowing I was leaving my son — it killed me inside,” she said. “I just remember looking at my baby, and kissing him, and crying, and not wanting to go.”

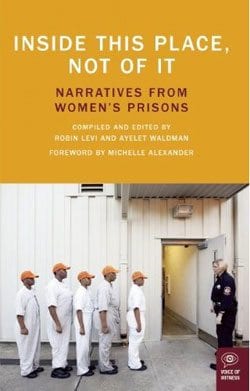

The harrowing story of Hamilton and other women imprisoned in the United States are the subject of Robin Levi and Ayelet Waldman’s new edited volume, “Inside this Place, Not of It: Narratives from Women’s Prisons.”

In it, Levi and Waldman chronicle not only the mistreatment and abuse women face in American prisons, but also the circumstances leading up to their incarcerations.

Although women comprise a small percentage of the American prison population — about 7 percent — they are the fastest growing group of inmates. In 1977, just 11,212 women were behind bars, and by 2007, that number ballooned to 107,000.

These prisoners face unique challenges as women, said Levi, human rights director at the Oakland, Calif.-based nonprofit Justice Now. “More than two-thirds of the women inside are primary caretakers of children,” she explained. “If they’re inside as primary caretakers, there is no one to take their child to see them, to make sure those connections are maintained.”

But more importantly, she continued, “They are in high danger of termination of their parental rights.” Under the Adoption and Safe Families Act, signed into law in 1997 under President Bill Clinton, the state will cut off parental rights if a child has been in foster care for 15 of the most recent 22 months. “For children three years or younger, it’s even more aggressive,” Levi adds. “In California, for instance, if you’re a child of three years or younger, in just six months your rights can be cut off. Those lengths of time are shorter than most people’s stints inside for what we consider low-level drug offenses.”

Women like Olivia Hamilton will also lose their children if they give birth in prison, usually between 24 and 72 hours of delivery. And others never get the chance to have children at all. “Because of these increased sentences,” Levi said, “women inside are in danger of spending their entire reproductive lives inside.” In addition to parental challenges, incarcerated women also face poor reproductive health (in particular, aggressive hysterectomies) and sexual abuse from prison guards and staff.

As with men, women of color are disproportionately represented among inmates, making up about half of the population — and over a third are black. An astonishing 90 percent of incarcerated women have suffered sexual and/or domestic abuse prior to being locked up, and 90 percent report annual incomes of less than $10,000.

“The result is that our women’s prisons are filled with people from the poorest, most vulnerable and marginalized segments of our society,” author and civil rights attorney Michelle Alexander writes in the book’s foreword. Their “offenses are often a consequence of their circumstances: lack of access to employment, familial stability, drug treatment, and protection from sexual and physical abuse.”

Teri Hancock, for example, was brutally abused by her stepfather growing up. He would slam her head through a wooden wall, beat her unconscious with a cast-iron frying pan, or make her lie on broken glass while he threw his boots onto her body — all while her mother did nothing except ask her not to call the police.

When she was 15, Hancock’s boyfriend, a drug dealer whom she met trafficking drugs for her stepfather, shot her mother and torched the family’s home. Hancock was charged with armed robbery, use of a firearm, arson and breaking and entering and was sentenced to four to fifteen years.

Emily Madison, meanwhile, was raised by a crack-addicted mother, and turned to sex work at the age of 16 in order to support her 13-year-old pregnant sister. Later, Madison had a child of her own, so she studied to become a medical assistant and landed a well-paying job as a health aide. But when one patient tried to rape her, Madison fought back, stabbed and killed the man, and was given a mandatory life sentence.

For Levi, understanding prisoners’ full stories should call into question the harsh sentences the courts frequently impose upon women. “We need to stop tossing people in jail for drugs or drug-related crimes, such as check forgery, or things related to survival — we need to start giving them real rehabilitation,” she said. “Many of these women are self-medicating because of previous childhood abuse, because it’s cheaper and easier to get heroin than it is to get real therapy.”

In the long term, Levi suggests models of restorative justice, in which victims and perpetrators work together to correct wrongdoing, as well as building stronger communities by creating greater support for childhood sex abuse and domestic violence victims, and a stronger educational system.

“I wanted people to see who these women are that we’re putting inside,” Levi said. “When people see them and hear their voices, they’ll ask — are we safer because they’re inside? Are our communities safer? What are we solving by doing this? These women deserve more from us and we deserve more as a community and as a society.”