Spellbinding from the start, “In the Red and Brown Water,” the play now at the Plaza Theatre, Boston Center for the Arts, opens with a view of its nine-member cast in silhouette. Humming in a low rhythm, they come forward on the tiny stage in unison, like dancers. When they stop, they resemble a pantheon of deities.

As the lights come up, all the actors leave the stage but two. The tall figure who was in their midst, a sprout of curly hair in a ponytail atop her head like a crown, is Oya, a slender beauty in red track shorts who is about to run a race. Her mother, broad of build, teases and bids good luck to her daughter.

“In the Red and Brown Water” is the first in a trilogy of plays by African American playwright Tarell Alvin McCraney. A companion production combining the other two plays, “The Brothers Size” and “Marcus; or the Secret of Sweet,” will join it in repertory from Nov. 10 through Dec. 3.

Presented by Company One, this staging is only the second production of the entire trilogy since its sensational U.S. premiere in 2009 at the Public Theater in New York.

McCraney, 31, currently playwright in residence at the Royal Shakespeare Company, has already received multiple prestigious awards, including the 2009 New York Times Outstanding Playwright Award for “The Brothers Size.” A 2007 graduate of the Yale School of Drama, McCraney was raised in a Miami housing project.

He sets his trilogy in public housing in the fictional bayou town of San Pere, La. While each character remains an entirely believable member of a family and community, he endows San Pere’s inhabitants with epic undertones as they go about their daily life.

Directed by Megan Sandberg-Zakian with simple and evocative sets (Erik D. Diaz), costumes (Sarah Patterson Nelson) and lighting (David Roy), the staging and utterly believable acting mine the interplay between the every day and the mythic in McCraney’s luminous script, which freely blends raunchy comedy and stirring poetry. As in life, the play makes quick turns between humor and joy as well as tension and loss.

While Oya (Miranda Craigwell) and her Mama Moja (Michelle Dowd) converse, the other actors watch behind the slatted walls that form the simple stage set. Also adding a stylized twist to the naturalism, the characters describe what they do as if observing it, a technique that expresses the character’s interior state.

While she and her daughter exchange a loving gaze, Mama Moja says, “They stand for each other.”

Oya is the axis around which the other characters turn as they interact with each other and her. A young woman with great self-possession and heart, she must reckon with her life. What will she do? What does she want? She has the blues. Although she suffers great losses and may long for a baby and a man, the playwright doesn’t entirely account for the depth of her melancholy.

Yet right away, Oya and her family and neighbors become important to us.

The prodigiously talented Hampton Fluker, a junior at Boston University’s School of Theatre, plays Elegba, a boy whose dream of blood and water gives the play its title. Elegba comes in to beg Mama Moja for candy and describes his dream, in which Oya floats, bleeding but not in pain. Mama Moja gives him the candy and tells him, “It mean you becoming a man lil Legba, my Oya a woman.”

Taking his leave, Elegba says, “Lil Legba begins to walk away like the half moon in the morning.”

In the course of the play, Fluker is alternately ferocious and tender as he portrays Elegba morphing from a bawling child and a crazed, candy-obsessed kid into a joyful father and at times, an oracle.

In a later scene, seconds after sassing Oya’s aunt, he says, “A spell comes o’er Legba.” His face turns pious and, his white hoodie growing translucent in the light, in a near-falsetto voice he sings a prayer for Oya.

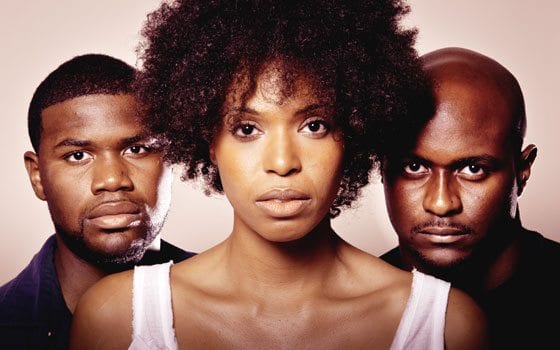

Nine actors perform the play’s 11 parts. All members of the terrific cast are black except Jerem Goodwin, who plays the shopkeeper and the Man from State, who offers Oya an athletic scholarship.

Michelle Dowd’s magnificent Mama Moja lingers as a presence long after her act one appearance. And Aunt Elegua (Juanita A. Rodrigues) is a Mardi Gras inside a plus-size dress.

Sizing up the coupling of Oya and the handsome Shango, Aunt Elegua says, “So yall sweet strong on each other or is this a bitter honey suckle yall sipping on.”

The playwright also has fun with a pair of mean girls, the glamorous Shun (Natalia Naman) and her pal Nia (the versatile Michelle Dowd), whose clichéd pettiness offers comic relief.

As the slick, womanizing Shango, Chris Leon injects enough sincerity and sweetness into his character to make him a believable candidate for Oya’s desire.

In the role of Aunt Elegua’s nephew Ogun Size, Johnny McQuarley embodies a good guy who only wants to take care of Oya. His Ogun stammers but then finds his voice and with the eloquence of a true heart speaks of having “a home inside me” for her.

McCraney gives each character her or his own language in body and speech. Shango’s signature caress of Oya’s ear, and phrases like “How could she not?” repeat and build, and at times take devastating new turns of meaning.

Only after the performance did I read in the program that McCraney draws the names of some characters from the Orishas, dieties in the Yoruba mythology that slaves brought from West Africa to America. So powerful is the interplay of myth and daily life on stage that this information amounted to an interesting footnote.

Performing briefly as a DJ in this production, James Milford joins Fluker and McQuarley in the three-man play that comes next, “The Brothers Size.” The entire cast minus Goodwin performs in the final play, “Marcus; or the Secret of Sweet.”

After Company One’s superb introduction to McCraney’s trilogy, I can’t wait to be back in San Pere, La., as it is conjured once more on the tiny stage of the Plaza Theatre.