Before the NAACP, the Niagara Movement fought for equal rights, human brotherhood

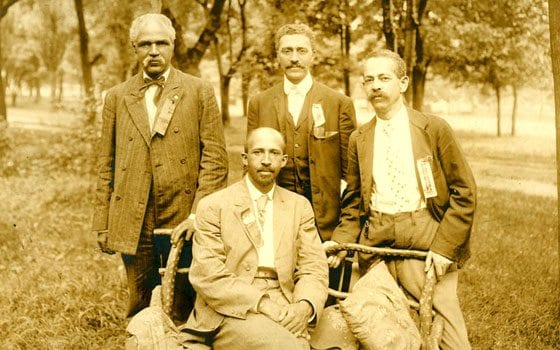

Author: University of Massachusetts at AmherstNiagara Movment members J.L. Clifford, L.M. Hershaw, F.H.M. Murray and W.E.B. Du Bois convened in Harper’s Ferry, W.Va., in 1906.

Author: University of Massachusetts at AmherstNiagara Movment members J.L. Clifford, L.M. Hershaw, F.H.M. Murray and W.E.B. Du Bois convened in Harper’s Ferry, W.Va., in 1906.

A little more than one hundred years ago, the civil rights organization that led to the formation of the NAACP held its largest gathering in Boston to help fight for racial equality in America.

By the time the Niagara Movement hit Boston for its annual conference in late August 1907, W.E.B. Du Bois was poised for battle.

The Movement had inched along the prior three years, and the strain of running an organization plagued with chronic infighting, limited resources and an almost insurmountable goal of attaining racial equality within turn-of-the-century America was a daunting task. Especially for an intellectual like Du Bois, more comfortable in academia than slapping backs and shaking hands.

But he tried. Lord knows, Du Bois tried.

“I was no natural leader of men,” Du Bois wrote years later. “I could not slap people on the back and make friends of strangers. I could not easily break down an inherited reserve; or at all times curb a biting, critical tongue. Nevertheless, having put my hand to the plow, I had to go on.”

And people, mostly African Americans, were willing to follow, largely because the other national black leader at the time, Booker T. Washington, the Wizard of Tuskegee, was considered part of the problem.

About 800 people showed up that day at Faneuil Hall — the largest gathering of the Movement — and listened to Du Bois try to stir the masses.

“We are not discouraged,” he declared. “Help us brothers, for the victory which lingers, must and shall, prevail.”

It would be a long fight, and the Niagara Movement did not make it to the end. In 1910, the all-black group gave birth to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and many of the members of the Niagara Movement dedicated their efforts to the new group. It was believed then that an organization of whites and blacks would be more effective in achieving goals of racial equality.

In his autobiography, published in 1940, Du Bois conceded that the Movement never really gained national traction.

“The Niagara Movement itself had made little progress, beyond its inspirational fervor, toward a united and constructive program of work,” Du Bois wrote in “Dusk of Dawn: An Essay Toward an Autobiography of a Race Concept.”

“It was therefore not without misgiving that the members of the Niagara Movement were invited into the new conference …”

It started with so much hope — and in direct opposition to Washington’s accommodationist policies. From where Washington sat, and that was frequently with U.S. presidents and titans of American industry, the “Negro problem” would disappear if the recently freed slaves would just learn to accept their role in society — at the bottom, in the fields, toiling still.

Making matters worse, Washington and his Tuskegee Institute controlled the lion’s share of money donated by liberal, well-intentioned whites for improving the lives and education of blacks.

“We shall not agitate for political or social equality,” Washington declared in his famous 1895 Atlanta Compromise speech. “Living separately, yet working together, both races will determine the future of our beloved South.”

That sort of thinking was abhorrent to Du Bois. Lynchings were prevalent in the Deep South, and the laws of the land, as evidenced by the 1896 U.S. Supreme Court Plessy v. Ferguson decision that legalized segregation, were as oppressive in black communities as armed vigilantes wreaking bloody havoc, first in Wilmington, N.C., in 1898, and then in Atlanta in 1906.

In June 1905, Du Bois circulated a call “for organized determination and aggressive action on the part of men who believe in Negro freedom and growth” and for those “opposed present methods of strangling honest criticism.”

Fifty-nine African Americans signed the statement, and in early June, 29 black men from 14 states caucused at a hotel in Fort Erie, Ontario. They decided to create a militant civil rights organization called the Niagara Movement.

Its stated objectives included: “Freedom of speech and criticism;” “manhood suffrage;” “the abolition of all caste distinctions based simply on race and color;” and “the recognition of the principle of human brotherhood as a practical present creed.”

Du Bois was elected general secretary of the organization, and in January 1906, the Niagara Movement was incorporated in Washington, D.C. Later that year, the Movement held its second annual conference in Harpers Ferry, W. Va., the site of John Brown’s attempted raid.

The message was the same as it was the first year: “We claim for ourselves every single right that belongs to a freeborn American, political, civil and social; and until we get these rights we will never cease to protest and assault the ears of America.”

Overall, the Niagara Movement was the most progressive faction of the Negro middle class, wrote Manning Marable in his 1986 biography, “W.E.B. Du Bois: Black Radical Democrat” — “the group most willing to jeopardize its material and political security in the effort to achieve democratic rights for the Afro-American people.”

One of the Movement’s founding members was William Monroe Trotter, like Du Bois, a Harvard man and the editor of the Boston Guardian. Together they drafted the Movement’s Declaration of Principles.

“Persistent manly agitation is the way to liberty,” they wrote in 1905. “ … We black men have our own duties … to respect ourselves, even as we respect others. But in doing so, we shall not cease to remind the white man of his responsibility. We refuse to allow the impression to remain that the Negro-American assents to inferiority, is submissive under oppression and apologetic before insults.”

Washington was not amused by the Niagara Movement or its members, whom he privately called “scoundrels.” Worse, Washington did everything he could to disrupt the meetings — and secure his position as preeminent Negro.

After discovering the initial proposed location for the first Niagara meeting, for instance, Washington sent two agents to the Buffalo, N.Y., area. One lieutenant, attorney Clifford Plummer, was able to get the Associated Press bureau in Buffalo to halt its coverage. After the Niagara Movement’s statements were circulated, another Washington minion ordered the National Negro Press Bureau to suppress any information about the group.

More troublesome, however, was the subtle racism of well-intentioned whites, many of whom agreed with Washington that blacks should not receive higher education and should start — and presumably finish — with vocational and industrial trades.

Four months after the Boston meeting of the Niagara Movement, Du Bois responded to Boston attorney Samuel May Jr., son of the staunch Garrisonian abolitionist, the Rev. Samuel J. May.

May Jr. had distributed a one-page leaflet appealing for funds for the Robert Hungerford Industrial School in Eatonville, Fla., “where,” the leaflet stated, “the population is comprised entirely of blacks.”

The circular went on to explain that “the best form of education for the negro — and the only one worthy of consideration at the present time — is industrial education.” It also urged “segregation of the races,” so that “the eternal discord arising from sectional differences over the negro, can be forever settled and silenced.”

In a letter dated Dec. 10, 1907, Du Bois wrote May and took him to task over what he characterized as May’s “extremely dangerous” and “unnecessary” beliefs on segregation and education.

“Segregation of any set of human beings,” Du Bois wrote, “be they black, white or of any color or race is a bad thing, since human contact is the thing that makes for human civilization, and human contact is a thing for which all of us are striving to-day.”

Du Bois saved his strongest argument for an attack against an over-reliance on industrial education.

“The second thing is the peculiar idea expressed that industrial education is the only education worthy of consideration for the Negro to-day,” Du Bois wrote. “… It seems to me that people who argue in this way, surely have forgotten that the College is the foundation of every system of education. And that in this respect the black men are no exception to the universal rule.”

May Jr. responded in kind. In a letter dated Dec. 14, 1907, May Jr. maintained his beliefs.

“I think the feeling quite generally is that it is best to bring to the front more prominently the industrial side of negro education and make the so-called higher education the next step forward,” May Jr. wrote. “Of course, there must be opportunities provided for the education of teachers, but it is impolitic to ask contributions for courses of education which are in advance of those which are open to the poor whites of the South, or even of the North.”

May Jr. went on to explain that “there has been, I think, too much discussion of the subject of higher education; it certainly has turned away a good many from giving on the theory that good artisans are being sacrificed to make way for preachers, lawyers, physicians, etc.”

As proof, May Jr. included a letter from a woman whom he described as “a prominent lady” of Boston that had refused to donate money to the school in Florida.

“In reply to yours I must tell that I no longer give to the blacks of the South,” the prominent woman wrote. “I think great trouble is in store for the poor whites from overdoing the education of negroes. They treat the poor whites so badly that in a few years the matter will have to be taken up. I give when I can to the education of the White Mountain boys and other whites. It is absolutely necessary to keep them up to the blacks. And the material is better to work on — they do not come to be so indolent as the colored.”

Du Bois was unmoved. In a subsequent letter to May Jr., dated Dec. 26, 1907, Du Bois wrote that it was “not a matter of offering exceptional opportunities for colored boys when the whites have no such opportunities.”

“Therefore in the teaching of teachers, and in the teaching of those who are to prepare teachers, there must be, not by and by, but now, higher institutions of learning,” Du Bois wrote.

“This has been proven again and again in the history of civilization. When those beneath are to be civilized it is not a matter of gradually raising them from beneath; it is a matter of putting ahead of them a group who can lift them up. The college is the foundation stone of the school system and not the cap-stone.”

Progress was indeed a long way in coming and Du Bois, for one, considered the Niagara Movement a start, a good start, but nowhere near a victory.

In his autobiography, Du Bois summed up the enemy in one word.

“Empire,” he explained, “… [is] the domination of white Europe over black Africa and yellow Asia, through political power built on the economic control of labor, income and ideas. The echo of this industrial imperialism in America was the expulsion of black men from American democracy, their subjection to caste control and wage slavery.”

“This ideology,” Du Bois sadly reported, “was triumphant in 1910.”