Conventional wisdom holds that Barack Obama’s stunning electoral victory ushered in a new era of “post-racialism” and “colorblindness.”

With the ultimate glass ceiling shattered for African Americans, the wisdom goes, race is no longer a problem in America — and no longer matters.

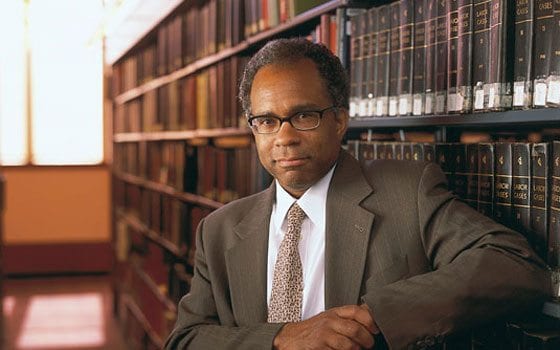

But Harvard Law School professor Randall Kennedy adamantly disagrees. Race, he contends, still means something. In “The Persistence of the Color Line: Racial Politics and the Obama Presidency,” Kennedy becomes the latest writer to contest post-racialism and colorblindness and to offer up his own vision of what it means to be black in the age of Obama.

For years Kennedy has written about controversial racial issues of the day. A graduate of Princeton and Yale Law School, a Rhodes Scholar and a law clerk to Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, Kennedy has also authored “Nigger: The Strange Career of a Troublesome Word” and “Sellout: The Politics of Racial Betrayal.”

Kennedy’s latest work, well written and thoroughly engaging, reconstructs Obama’s rapid ascent from little-known state senator to first-term president and offers fresh analysis of the president’s treatment of race, as well as the racial climate that surrounds him.

Examining the president’s famous speech on race, “A More Perfect Union,” Kennedy observes that Obama uses the passive voice when discussing racial wrongdoing — “blacks were prevented,” “loans were not granted,” “black homeowners could not access,” “blacks were excluded.” “In his narrative,” Kennedy writes, “slavery and segregation happened without enslavers or segregationists.”

“Obama’s use of the passive voice here is no accident,” he continues. “It is part of an effort to discuss racial affairs without being accusatory, without hurting feelings, without affronting the sensibilities of the white audience.”

Kennedy’s analysis stands at odds with the lavish praise of other black commentators. He quotes journalist Joan Morgan, who said, “A More Perfect Union” would “take its rightful place in the prestigious canon of seminal American speeches — right up there with ‘I Have a Dream’ and the Gettysburg Address.” Washington Post veteran Eugene Robinson similarly applauded the speech, calling it “stunning.”

His criticism of “A More Perfect Union” signals Kennedy’s critique of Obama in general. Although the author openly acknowledges his great admiration for the president, he notes that in his years on the national stage, Obama has “consistently attempted to evade racial issues … This is the Obama way.”

While acknowledging his contributions to the diversification of the government, like his appointments of Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Attorney General Eric Holder, as well as the first black administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, Lisa Jackson, and the first black administrator of NASA, Charles Bolden, Kennedy points to the president’s silence on affirmative action and mass incarceration, two important issues for people of color.

Kennedy recognizes the politics behind this avoidance, but concludes, “Obama’s cautiousness has prompted him on occasion to cede excessive ground to the right.”

While Kennedy is thorough and nuanced in his critique of Obama, he is surprisingly reserved in his criticism of the racial climate surrounding the president, particularly the John McCain and Hillary Clinton campaigns in 2008.

Kennedy inexplicably skips over any discussion of vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin’s barb that Obama has been “palling around with terrorists” and the racial epithets and violent threats frequently voiced by audience members at McCain-Palin rallies. Instead, he commends McCain for not “playing the race card,” especially his refusal to revisit the Rev. Jeremiah Wright scandal.

“In retrospect, a striking feature of the campaign of 2008 was not the presence but the paucity of racial misconduct,” he writes.

Similarly, Kennedy analyzes Geraldine Ferraro’s comment, “If Obama was a white man, he would not be in this position,” by saying there was “considerable truth” to Ferraro’s claim that blackness helped Obama in some ways.

While many liberal commentators were quick to slap the “racist” label on Ferraro’s comments, her controversial insult points to a larger theme in Kennedy’s work. Although the color line persists, he argues, it is not the same as it once was. Blackness, once an insurmountable obstacle, can now be an advantage. “But blackness matters now in ways that are not always detrimental,” he writes. “Identifying as black can also ‘assist’ a candidate.”

Reflecting on John F. Kennedy, who in 1960 became the first Catholic to win the American presidency, the author observes that Obama, like his Democratic predecessor, succeeded in large part because he was able to turn “a social stigma into political capital.”

But this momentous turn in race relations that President Obama represents is not cause for excessive celebration, Kennedy warns. “Americans should not be boastful about learning that lesson at this late date; it should have been taken for granted long ago.”