Before the opera came the drama. Some fans of “Porgy and Bess” may be surprised, but DuBose Heyward and his wife Dorothy adapted his own story about the titled Charleston, S.C. couple into a play eight years before the 1935 collaboration with George and Ira Gershwin.

Even that historic folk opera, which premiered at the Colonial Theatre, was produced by the Theatre Guild. Now the often-evolving work — with 1942 and 1953 stage revivals as well — is being re-imagined by American Repertory Theatre artistic director Diane Paulus with a new adaptation by Pulitzer Prize-winning African American playwright Suzan-Lori Parks (“Top Dog/Under Dog”) and new arrangements by OBIE-award-winning musician Diedre L. Murray (“Eli’s Coming.”)

No matter how you like “Porgy and Bess” — operatic or theatrical — you will want to make up your own mind about “The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess,” which officially opens at the Loeb Drama Center Aug. 31.

One thing is very clear: The five actresses who recently spoke to the Banner about the current revamping are totally enthusiastic about this theater-centered version. While this theatrical edition heads for Broadway in December (with a January opening), the women were sufficiently excited about the A.R.T. world premiere by itself to devote their answers and comments to the Cambridge run alone.

The African American quintet — Nikki Renee Daniels (Clara), NaTasha Yvette Williams (Maria), Heather Hill (Lily) and ensemble members Andrea Jones Sojola and Alicia Hall Moran — are very much women of “Catfish Row,” the vivid waterfront area of Charleston that serves as the early 20th century setting of the drama.

Daniels may be familiar from North Shore Music Theatre runs of “Ragtime” and “Beauty and the Beast” and Williams from the Boston run of the musical “Abyssinia.” Some theatergoers may give most of their attention to physically challenged beggar Porgy (here Norm Lewis) and striking seductress Bess — (here four-time Tony Award winner Audra McDonald of “A Raisin in the Sun,” among others).

Others may be fascinated by stylish gambler Sportin’ Life, here David Allen Grier. Yet the characters played by the interviewed women and their counterparts in the sizeable A.R.T. cast are the real foundation of the show’s vibrant African American community.

That sense of community is a major area of the two and a half hour production’s re-imagining. Hill spoke of “this production’s focus on dialogue” as a key part of that sense, and Daniels observed, “Suzan Lori [Parks] has strengthened [Heyward’s] book. Some of the scenes have added dialogue.”

Also instrumental to the show’s attention to community are the back-stories of the actresses’ respective characters. As Sojola explained, “We were asked to come up with a presentation of our character. We all had to come up with answers to five questions.” Those questioned ranged from each character’s greatest strength and weakness to a signature prop or object, a brief self-description and something nobody knows about her.

Take Clara for example. Daniels spoke of her “loving others unconditionally” as the strength and “acting without thinking things [through]” as the weakness. She described Clara as “the one who always puts others’ needs above her own.”

For her part, Hill knits onstage as an ongoing activity. Moran noted another supplement to the sense of community — the benefit of the actors’ own family members. Referring to children backstage during rehearsals, she remarked, “The tenderness we feel backstage [toward them] translates onstage.”

That tenderness is most personal for Williams: Her daughter McKenzie Christina is playing Clara’s daughter, and son Nile Christopher serves as an alternate.

“There are many husbands [of performers] at rehearsals,” she added. Moran also summed up the backstory efforts of Parks. “Suzan Lori has given one of the characters a parent, a mother,” she noted. “It kind of humanizes. We didn’t spring from nowhere.”

Hill concurred. “There are siblings,” she said. “There are changes.”

Williams praised the “collaboration of Parks, Paulus and the cast.” “The work that we’re supposed to do at home together [about our respective roles], we did together,” she submitted. “We don’t usually have the luxury of this kind of character work,” she stressed.

Hill added that back story is provided even for a pivotal character like murderous stevedore Crown (played by Phillip Boykin) with whom Porgy vies for Bess. “He’s more than just a bad boy,” she offered. “’You have a backstory.

Considerable care has been taken with dance as well. Here noted choreographer Ronald K. Brown, Moran observed, “put a psycho-physical overlay on the men protecting aspects of the characters’ manhood.”

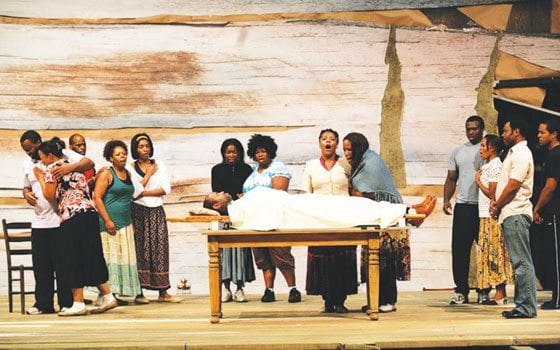

She credited him for expressing parts of the women and the men’s roles in their stage moves. There is even dancing at a funeral to go along with a tradition of reverential music. Daniels pointed as well to a sparseness of movement quite often as characters speak — unlike in opera, where performers often pass many people in a scene.

“This is drama-driven,” Hill concluded approvingly.