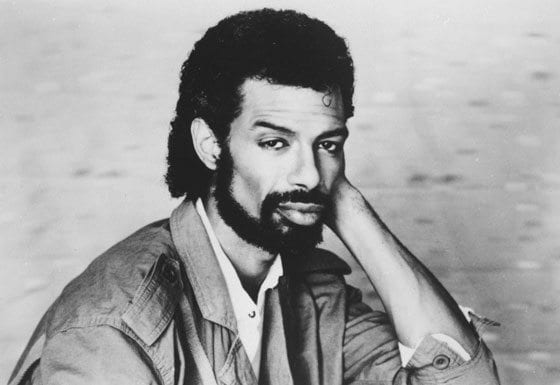

NEW YORK — Musician Gil Scott-Heron, who helped lay the groundwork for rap by fusing minimalistic percussion, political expression and spoken-word poetry on songs such as “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” but saw his brilliance undermined by a years-long drug addiction, has died at age 62.

A friend, Doris C. Nolan, who answered the telephone listed for his Manhattan recording company, said he died Friday afternoon at St. Luke’s Hospital after becoming sick upon returning from a trip to Europe.

“We’re all sort of shattered,” she said.

Scott-Heron was known for work that reflected the fury of black America in the post-civil rights era and also spoke to the social and political disparities in the country. His songs often had incendiary titles — “Home is Where the Hatred Is” or “Whitey on the Moon” — and through spoken-word and song he tapped the frustration of the masses.

Yet much of his life also was defined by his battle with crack cocaine, which led to time in jail. In a 2008 interview with New York magazine, he said he had been living with HIV for years, but he still continued to perform and put out music; his last album, which came out this year, was a collaboration with artist Jamie xx, “We’re Still Here,” a reworking of Scott-Heron’s acclaimed “I’m New Here,” which was released in 2010.

He also was still smoking crack, as detailed in a New Yorker article last year.

“Ten to fifteen minutes of this, I don’t have pain,” he said. “I could have had an operation a few years ago, but there was an 8 percent chance of paralysis. I tried the painkillers, but after a couple of weeks I felt like a piece of furniture. It makes you feel like you don’t want to do anything. This I can quit anytime I’m ready.”

Scott-Heron’s influence on rap was such that he sometimes was referred to as the Godfather of Rap, a title he rejected.

“If there was any individual initiative that I was responsible for it might have been that there was music in certain poems of mine, with complete progression and repeating ‘hooks,’ which made them more like songs than just recitations with percussion,” he wrote in the introduction to his 1990 collection of poems, “Now and Then.”

He referred to his signature mix of percussion, politics and performed poetry as bluesology or Third World music. But then he said it was simply “black music or black American music.”

“Because black Americans are now a tremendously diverse essence of all the places we’ve come from and the music and rhythms we brought with us,” he wrote.

Nevertheless, his influence on generations of rappers has been demonstrated through sampling of his recordings by artists, including Kanye West, who closes out the last track of his latest album with a long excerpt of Scott-Heron’s “Who Will Survive in America.”

Politically outspoken rapper Michael Franti said in a statement Saturday that Scott-Heron’s talent was his ability to “make us think about the world in a different way, laugh hysterically about the ironies of American culture, anger at the hypocrisy of our political system, all to a beat that kept us on the dance floor, with a voice and flow that kept you waiting with anticipation for the next phrase.”

Scott-Heron recorded the song that would make him famous, “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” which critiqued mass media, for the album “125th and Lenox” in Harlem in the 1970s. He followed up that recording with more than a dozen albums, initially collaborating with musician Brian Jackson.

Throughout his musical career, he took on political issues of his time, including apartheid in South Africa and nuclear arms. He had been shaped by the politics of the 1960s and black literature, especially the Harlem Renaissance.

Scott-Heron was born in Chicago on April 1, 1949. He was raised in Jackson, Tenn., and in New York before attending college at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania.

Before turning to music, he was a novelist, at age 19, with the publication of “The Vulture,” a murder mystery.

He also was the author of “The Nigger Factory,” a social satire.

Associated Press