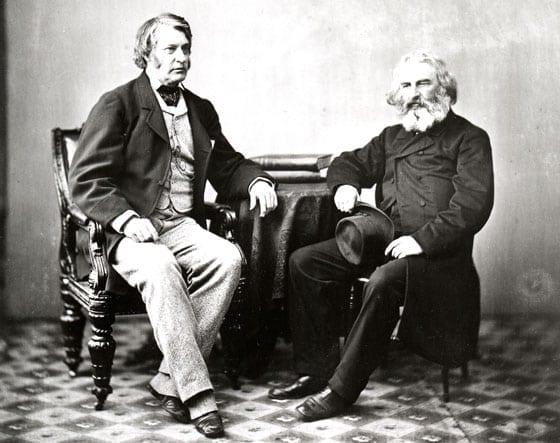

Author: courtesy of Longfellow House-Washington’s Headquarters National Historic SiteCharles Sumner is pictured here with Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, a famous poet, Harvard professor and Sumner’s best friend.

Few people may realize that the statue seated on the traffic island on Massachusetts Avenue in Harvard Square is a replica of Charles Sumner. Even fewer may know who Sumner was or appreciate his contributions to the abolition of slavery.

Two hundred years after his birth, the Charles Sumner Bicentennial Committee is attempting to revive Sumner’s historical celebrity by promoting his work and educating the public about his civil rights activism.

Since Jan. 6, Sumner’s actual birthday, the committee has held various events to celebrate the life and historical significance of the Harvard-educated abolitionist and Massachusetts statesman. The most recent gathering was the forum held last month at the First Parish Universalist Unitarian Church in Harvard Square.

Spearheaded by the National Park Service, the Bicentennial Committee is comprised of the Boston African American National Historic Site, Cambridge Forum, Friends of the Longfellow House, Friends of Mount Auburn Cemetery, Harvard University, Longfellow National Historic Site, Massachusetts Historical Society and the Museum of African American History.

A week before the forum, dozens of supporters gathered in front of the church in the rain for the preliminary dedication to Sumner. Several students from the Haggerty School recited the poem “Charles Sumner,” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, the famous poet, Harvard professor and Sumner’s best friend.

Nancy Jones, a park ranger from the Longfellow House-Washington’s Headquarters National Historic Site, in Cambridge, led a ceremony rededicating the Sumner statue, and placed a bouquet of flowers next to the seated figure.

The statue in Harvard Square was designed by Anne Whitney in 1875, but was not installed until the 20th century.

The Boston Art Committee held a national competition for the design of the Charles Sumner memorial statue. All entries were made anonymously and the committee did not realize that a woman sculpted the figure.

When the committee discovered Whitney’s identity, it denied her the award, claiming that “a woman could not properly model a man’s legs.” The prize then went to Thomas Ball, whose statue of Sumner is located in Boston’s Public Garden.

Whitney resumed her project 25 years later and produced a full-size bronze cast statue, which was eventually installed in its current Harvard Square location in 1902.

After the dedication, the crowd poured into the church to hear the panel’s presentation. Three speakers shared biographical information, anecdotes and opinions about Sumner and the political issues dominating the political and social climate of his time.

During the second half of the forum, audience members asked questions about Sumner and his contemporaries.

John Stauffer, Harvard professor of African American studies and Chair of the History of American Civilization, moderated the discussion. The other two panelists included Daniel Coquilette, a Harvard Law School visiting professor, and Beverly Morgan-Welch, executive director of the Museum of African American History in Boston and Nantucket.

The three shared detailed information about Sumner, who was born in Boston and grew up in a multiracial neighborhood in Beacon Hill. Sumner’s father, Charles Pinckney Sumner, was the sheriff of Suffolk County and an ardent anti-slavery activist.

“This is one of the greatest men in U.S. history,” said Coquillette. “Why is he not regarded as such like Lincoln?”

Answering his own question, Coquillette claims that race relations over the years have continued to keep Sumner a divided figure. “Even after nearly two centuries, Sumner is still constantly under attack and his causes are, as well,” he said.

“The Civil War was not about states’ rights,” Coquillette continued. “It was about slavery. And if anyone wants to take me on about this, I am ready.”

The half-joking statement invoked chuckles from the pews. However, no one challenged his claim.

Coquillette went on to describe the notoriously violent altercation between Sumner and South Carolina congressman Preston Brooks. Sumner had made outspoken and insulting remarks about Brooks’ cousin, Sen. Andrew Butler, and his proverbial “mistress,” slavery. In 1856, Brooks severely beat Sumner with his cane on the floor of the United States Senate.

Sumner took three years to recover from his injuries and returned to the senate in 1859. Despite the setback, he resumed his efforts in the anti-slavery movement, garnering the reputation as a rude, outspoken, shrill extremist with radical views on civil liberties.

“The division of North and South was evident that day in the senate,” said Coquillette. “Preston Brooks never went to jail for his violence … he was a coward through and through.”

When asked about the influence of Sumner’s upbringing on the rest of his life, Morgan-Welch underscored the connection between the two.

“Growing up in that integrated community really formed him,” she said. “Blacks in Beacon Hill knew whites of great prominence and helped put them in those very positions of power.”

Coquillette added, “[Sumner] was true to his upbringing and neighborhood. He had exposure to high society, traveled around Europe and spoke many languages, but he never forgot his roots.”

An audience member reiterated the issue of Sumner’s obscure reputation, asking why the public isn’t as familiar with him as with other historical figures.

Coquillette replied, “Charles Sumner is not a household name because what the argument was then continues today. We haven’t confronted it yet. His greatness is tied up in the problems we face today as a divided nation.”

Morgan-Welch agreed, likening the North and South during The Civil War to modern day “blue” and “red” states. “There are still many people who argue how brash and rude the abolitionists were, as though slavery were a good idea. There is still a lot of debate about it.”

Stauffer summed up the discussion by adding, “The respect afforded [Sumner] in Congress contradicts the image of a shrill, unbending, difficult person. He was demonized by many historians, particularly in the South, and is still a controversial figure.”