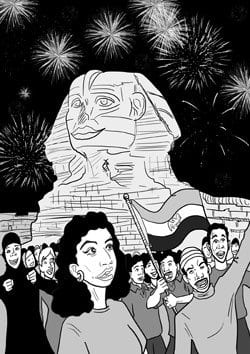

An Egyptian revolution yet to come

|

February 11, 2011 |

It is not a revolution in Egypt, at least not yet anyway, even though Hosni Mubarak has finally decamped from the presidential palace after nearly 30 years of autocratic rule. Much more must be done to install a new democratic order.

Mubarak’s departure was foreshadowed by a series of concessions to the masses of angry Egyptians who filled the streets for almost three weeks. First, he pledged not to run in the September election and then that his son Gamal, the handpicked successor in waiting, would not either. The president dismissed his cabinet. His government opened negotiations with protest leaders, and promised to reform the constitution.

None of that was enough for the protesters, nor should it have been.

After abuse after abuse of power, Mubarak had lost the trust of the country’s long-suffering people, a quarter of whom live in poverty. His regime had only responded to popular will, grudgingly and fitfully, when doing so served to extend his rule. The government knew nothing of transparency or accountability.

The civilian bureaucracy he leaves behind remains populated by members of his party. That is a good reason the apolitical military is the best choice to run the interim government, even though that transfer of power does not follow the niceties of the constitution. That hardly mattered before.

Egyptians have a high opinion of the military. However, little is known about it because the Ministry of Information has prohibited the media from independent reporting about military affairs. An institution with a chain of command is not naturally democratic, so the country’s public should temper hope with wariness.

The head of the military high command, and thus the interim government, is Mohamed Hussein Tantawi, a Nubian who has been defense minister for 20 years and holds the lofty rank of field marshal. His age, 75, may make Tantawi less tempted to cling to power.

The important check, literally, to ensure that Tantawi permits Egypt’s first fair election and then hands power to civilians, comes from Washington. That $1.3 billion a year in U.S. military aid gives President Barack Obama leverage.

As soon as Egyptians have resumed normal life, the interim government must repeal the emergency law, which prohibits protests of more than a few people on public property and authorizes indefinite detentions without charges. The military should also rein in the hated security police, slash their bloated ranks and narrow their duties to legitimate ones identifying and pursuing violent subversives.

The diffuse groups of protesters also have much work to do to make it more likely the election will produce the open, responsive and freedom-loving government they desire.

The protesters have to organize into a political movement. Has anyone started collecting an e-mail list of the protesting masses, Obama-style? Holding the election sooner, as some protesters want, would actually undermine their cause. Others want to bar the Muslim Brotherhood from fielding candidates; that would be undemocratic.

Egyptians also need time to have a full debate about the kind of democratic nation they want, in particular spelling out Islam’s role, minority rights, civil liberties and media freedoms.

It will not be known until the fall if the popular uprising concludes in a new democratic order. If so, then it will be a revolution.

Kenneth J. Cooper is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and a former Fulbright Scholar at Cairo University.