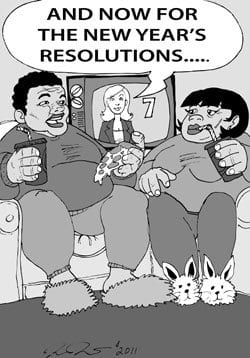

Resolutions forgotten

This is the time for those annual efforts at self-improvement, fragile though they may be. Human nature demands a personal recognition of one’s many faults. The alternative is to insist upon the attainment of perfection — an uncomfortable idea for most people.

Once the flaws are acknowledged, there is then a duty to correct them. But that is not so easy to do. The faults have become embedded in habits, and for many people, our habits are who we are. The elimination of some flaws takes on an unpleasant undertone. One asks, “Who will I be when it’s gone?”

In order to maintain their identity, people tolerate the most egregious anomalies, and redefine them as normal. Consider obesity, for example. Just being a bit overweight does not count. One must have attained physically distending dimensions to be considered. Absent a special medical condition, the only way to become obese is to overeat.

During the process of enlargement, men might comment that they are becoming more robust, manlier. Women might insist that they are becoming more curvaceous and more feminine. Both genders will tend to assert that they are more appealing to the opposite sex, now that they have more avoirdupois.

The diet battle provides a clear example of the conflict between the human psyche and a real commitment to New Year’s resolutions. Every January health clubs become overcrowded. By March the number of patrons thins. There are numerous other examples to indicate that despite the popularity of the idea of New Year’s resolutions, most people are really unwilling to change.

As Popeye the cartoon character said, “I am what I am.”

A standard of correction

Progressive penal systems call themselves euphemistically “Department of Corrections.” However, the rate of recidivism indicates that few inmates are really corrected. According to a 2006 study by the Commission on Safety and Abuse in America’s Prisons, 67 percent of former prisoners are arrested again within three years of their release and 52 percent are sent back to prison.

Despite those unfavorable statistics, enlightened prison systems establish educational programs and personal counseling to enable inmates to overcome the inadequacies that contributed to their conflicts with the law. Prisoners with long sentences would have little motivation to participate in these programs if it was unlikely that they would ever be released.

The parole system provides an opportunity for inmates who have demonstrated their rehabilitation to be released before completion of the term of their sentences. They must come before the parole board to state their case and their fate is then determined. Whenever a parolee commits another crime, the public is outraged.

Some citizens want prisoners to serve the full term of their sentences, regardless of any indication of their rehabilitation. However, others support a policy of early release, but they question whether the parole board has a sound standard that petitioning inmates must meet.

Ben LaGuer has been imprisoned since 1983, and he is serving a sentence for rape of life with the eligibility of parole after 15 years. Because he has consistently proclaimed his innocence, he has been denied parole primarily because the insistent assertion of his innocence is considered to be a lack of remorse.

There is little likelihood that LaGuer would rape a 59-year-old woman if released, as he was accused of doing 27 years ago. It was far more likely that Dominic Cinelli, a lifer with a record of armed violence, would revert to crime. He was paroled in 2009 and he gunned down a police officer less than two years later while trying to escape from a robbery.

Where is the justice for LaGuer?