As she walked through her office building one day, Caroline Hunter noticed something strange — a mock-up of a South African passbook.

At the time, Hunter knew little about South Africa, a country on the other side of the world from her workplace in Cambridge, Mass. But she knew about apartheid, and understood that this enlarged photo identification card meant something was not right.

Hunter, a 21-year-old chemist working for the Polaroid Corporation, stumbled upon evidence that her employer supported apartheid. But unlike anyone else at the time, she and her colleague, photographer Ken Williams, decided to do something about it.

The year was 1970, decades after the apartheid regime took hold of South Africa, but many years before the international community would realize and rally against its brutality.

South African passbooks, which Nelson Mandela described in his autobiography as “the hated document,” was a photo identification booklet used by the apartheid regime to control and monitor the movements of the country’s 21 million blacks.

The Pass Laws Act of 1952 required black males over the age of 16 to carry their passbook at all times — and to present it to white officials upon request.

Failure to do so resulted in jail time.

Although various pass laws had been in effect since the eighteenth century, passbooks became a powerful symbol of apartheid and cause for widespread protest.

In March of 1960 — a decade before Hunter found the mock-up at Polaroid — thousands of South Africans gathered in front of the police station in Sharpeville, a township outside Johannesburg. Protesting the pass law, the crowd of 7,000 refused to carry their passbooks and presented themselves to law enforcement officials for arrest.

However, police shot at the crowd, killing 69 and injuring 180 in what became known as the Sharpeville Massacre.

Polaroid had been doing business with South Africa since 1938, a decade before apartheid became a formalized legal system. The company sold its products to the government and military. Most important was its ID-2 system — which consisted of a camera, instant processor and laminator.

This new system could generate a photo identification card in just two minutes and more than 200 in an hour — exactly the technology the South African government needed to enforce its Pass Laws Act.

“Polaroid was unique in that it was the only company that could fulfill South Africa’s need for instant identification systems — whether passbook or race identity card,” Hunter later testified to the United Nations’ Special Committee on Apartheid.

After finding the mock passbook, Hunter and Williams got to work. They distributed fliers around their workplace to alert their colleagues: “Polaroid imprisons black people in 60 seconds.”

They also demonstrated in front of the company’s headquarters in Technology Square and formed the Polaroid Revolutionary Workers Movement (PRWM).

Although Hunter was only working at Polaroid for about a year, she was no stranger to “causing a stir” at the company’s headquarters. Before the PRWM, Hunter fought for the same salary as her white counterparts. She also led an organized effort to support a dishwasher burned by cleaning chemicals.

The PRWM presented Polaroid with three demands: disengage from South Africa, publicly denounce apartheid in both the United States and South Africa, and donate all profits made from South Africa to recognized African liberation movements.

Up until that point, Polaroid had enjoyed its reputation as a liberal company, and boasted itself as an “equal opportunity employer.”

But Polaroid executives did not take well to PRWM protests. According to a 1971 article in Ramparts magazine, Polaroid Vice President Arthur Barnes said, “We don’t deal with demands from the street.”

While Polaroid denied its role in apartheid, Hunter and Williams were not satisfied — Polaroid still sold its products to and had factories open in South Africa — so the PRWM launched an international boycott of Polaroid products until the company completely withdrew.

As PRWM protests grew, Polaroid made a controversial donation of $20,000 to Roxbury’s Black United Front, an organization supporting the boycott. Black groups saw this gesture as an attempt to buy off the movement, and refusing to back down, gave the money to South African liberation groups and a Black United Front branch in Illinois.

Hunter and Williams were the first American activists to stand up and challenge their employers’ South African investments. Their Cambridge-based protest quickly became a national story.

Facing such intense media pressure, Polaroid responded, this time buying a full-page ad in the Boston Globe to explain its position on South Africa, and to announce its sending a multi-racial envoy on a fact-finding mission in South Africa to understand the “complexities of the situation.”

“Because, if a corporation has a conscience it must be considered to be the collective conscience of the people who manage the company and those who work there,” the ad said. “Injustice to blacks in South Africa concerns many black people and many white people no matter where they live.”

The envoy returned with the conclusion that it should not withdraw — simply improve working conditions there. The group claimed its decision was based on the wants of black South Africans, but didn’t acknowledge that at the time, openly calling for foreign divestment was a crime punishable by death in South Africa.

Hunter and Williams were not convinced. “Then, as now, Polaroid responded with empty public gestures and a cover-up of its continued trade with the South African pass system and government,” she testified to the United Nations in 1977.

After her testimony, Polaroid fired Hunter, citing the contradiction that “ [she] accepts the benefits of employment by the Polaroid Corporation while [striving] to hinder or counteract the effectiveness of its operations.” By that time, Williams had also quit his job.

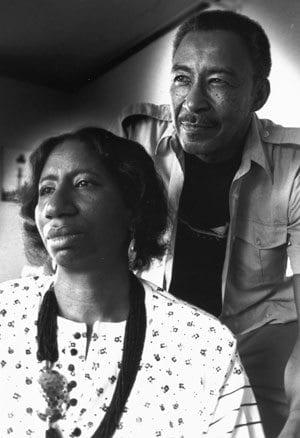

But amidst their struggle Hunter and Williams also found love in each other, married, and together endured the personal sacrifices of their activism. Hunter was jobless for two-and-a-half years and lived off $69 in weekly unemployment checks, according to a Banner article from 1990. “I taught kitchen chemistry at Roxbury Multi-Service Center, got involved in community activities and eventually found my way into education, working with adults going for their high-school diploma,” she said.

But their hard work and sacrifices paid off. By 1977, Polaroid completely pulled out of South Africa, and the international divestment movement — which eventually crippled apartheid — was on its way.

Hunter and Williams’ efforts have recently been featured in the documentary “Have You Heard from Johannesburg: The Bottom Line.” This film, produced by Connie Field, chronicles the international South African divestment movement.