New York — Last year, the late pioneer D.J. Dewey Phillips (who died of heart failure in 1968 at the age of 42) was rewarded with a brass note on famed Beale Street in Memphis. A white disc jockey who loved all music, Phillips — also known as “Daddy-O-Dewey” — played an eclectic mix of blues, RandB, country and dance records on WHBQ radio and WHBQ-TV/13 that helped to integrate American radio and television music in the late 1940s and all through the 1950s.

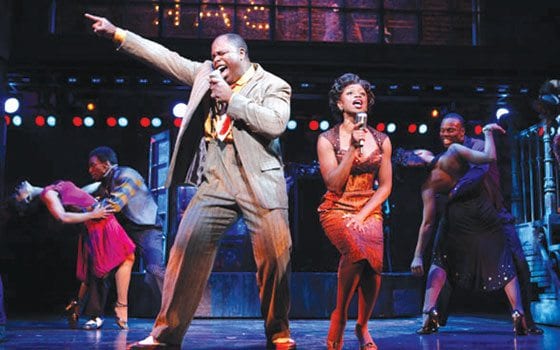

Now the Broadway show “Memphis” is bringing the important story of the struggle to integrate American music and popular culture to exuberant life at the Sam S. Shubert Theatre in New York. While both the Joe DiPietro book and the David Bryan-Di Pietro score need more of Phillips’ own boldness, the high-stepping and big-voiced cast supply the kind of fire and soulfulness such a well-intentioned musical demands.

There are two reasons why “Memphis” may seem familiar to savvy theatergoers. First of all, DiPietro and Bryan first tried out their collaboration at Beverly’s famed North Shore Music Theatre (with Theatre Works) under the artistic direction of Jon Kimbell back in 2003 — with leads Chad Kimball (a Boston Conservatory graduate), Montego Glover and featured performer J. Bernard Calloway (who earned a master’s degree in acting from Brandeis) — all in the Broadway production as well.

Second, several of the show’s themes should call to mind earlier award winners. “Hairspray” already spoke about racism (although in a campy John Waters-based show) and “Dreamgirls” railed against the exploitation of African American musicians and performers by white label heads. Quite frankly, both shows possess more hummable scores than “Memphis” and “Dreamgirls” takes a much more envelope-pushing stand for black empowerment.

If “Memphis” still compels attention much of the time, Kimball’s knockout work as Dewey-based Huey and Glover’s big-voiced performance as the plucky DJ’s black girlfriend and ambitious singer Felicia provide a large part of the reason. Both performers demonstrated Broadway-big voices and talent back at the North Shore. Kimball continues to sing with rich phrasing and sport the right combination of Tennessee drawl and off-beat stage moves that help to define an undaunted iconoclast like Huey.

This critic saw Glover bring affecting vulnerability and strong determination to the role of Felicia at the North Shore Music Theatre. Tracee Beazer, stepping in for Glover at the performance I saw on Broadway, sang with nearly as strong resonance on Felicia’s impassioned solo “Colored Woman” and brought similar forcefulness to the heroine’s high and low moments on the way to stardom and validation.

The third “Memphis” original, Callaway, once again makes a strong impression as Felicia’s gutsy brother and black club owner Delray. Calloway finely balances Delray’s sibling defensiveness — especially with Kimball on “She’s My Sister” — and his gradual acknowledgement of Huey’s authenticity.

Big talents aside, the flaws in DiPietro’s book remain. The character of “Mama” in Huey’s first act inexplicably makes a complete turnaround in the second act — so much so that the peppy song “Change Don’t Come Easy” finds her actually leading the gospel-propelled number — with Cass Morgan doing well trying to make Mama’s turnaround convincing.

If Huey and Felicia are severely roughed up by white bigots, the general racist climate of the 1950s South does seem relatively understated throughout the musical. A different kind of liberty with the facts involves Huey losing his television show for kissing Felicia in what is actually a romance created for “Memphis. “

Kimball, Glover (and Beazer) and Calloway go far in covering over these weaknesses in strong numbers enhanced by Sergio Trujillo’s fast-paced and sharply synchronized choreography — most notably in the funky club opener “Underground” and the very rousing finale “Steal Your Rock and Roll.”

Rounding out strong supporting work are Derrick Baskin as a high-principle black bartender with a personal moment of truth and James Monroe Iglehart as a black janitor whom Huey befriends. David Gallo’s sets and Paul Tazewell’s vividly complement the musical’s worthy if sometimes simplistic contrasts of hateful whites and beleaguered African Americans.

When Huey is dismissed from his television show, he is flatly told “You are through here. You are nothing special anymore.” By contrast, “Memphis” is far from through with Broadway. Although the story of the trail-blazing effort of Huey (read Dewey Phillip) and Felicia’s rise ought to be even more special, the soaring ensemble at the Shubert does catch fire with 1950s soul.

For ticket information, call 212-239-6200 or visit http://memphisthemusical.com.