More than 50 years ago, noted sociologist Kenneth Clark detailed the sense of racial inferiority in a landmark study involving black children’s characterization of black and white baby dolls. That study was pivotal to the success of the 1954 Brown decision of the U.S. Supreme Court that brought an end to public segregation.

Left unanswered in that visceral debate were questions on the role of modern day advertising and marketing campaigns in perpetuating racial stereotypes. In recent years, similar doll tests — where some blacks still choose white dolls as “prettier” — have echoed Clark’s results from the early 1950s. How should the black community counter these psychological obstacles?

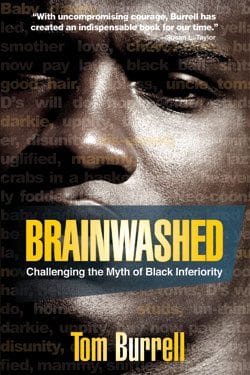

In his book “Brainwashed: Challenging the Myth of Black Inferiority,” Tom Burrell, a nationally respected media and advertising expert, charts a strategy which identifies the myths of inferiority, separates fact from fiction, and reconditions the black mind. Burrell, who with a partner launched Burrell Advertising in 1971, helped pioneer a firm which designed commercial campaigns aimed at black consumers of popular brands.

This experience gave Burrell unique insight into the genius of successful propaganda and its effects. He learned how and why corporations expected him to spin their products toward his people. In “Brainwashed,” the author dissects the well-worn stereotypes surrounding black Americans, traces their origins and offers alternate mindsets.

Though black nationalists, Pan-Africanists and separatists have long labored to heal the black mind, or mental “slavery,” Burrell’s approach is unique in its analysis of a centuries old, deliberate campaign intent on convincing both black and white America that blacks are sub-human, and innately immoral.

The book takes on all of the myths and introduces lesser-known truths. Chapters include “Relationship wrecks — Why can’t we form strong families?”; “Studs and sluts — Why do we conform to sexual stereotypes?”; “Buy now, pay later — Why can’t we stop shopping?” and “D’s will do — Why do we expect so little of each other?”

Burrell connects relationship woes to families torn apart by slavery, then unemployment and outlandish consumerism to a disproportionate need for status and the live-for-today sentiment fostered by oppression. In Burrell’s view, academic under-achievement is residue from our ancestors being punished for reading, our belief that we were mentally inferior, as we were told, and buying into separate categories, or tokenism, for black and white achievement.

To support his case, the author quotes authorities whose programs have overcome obstacles created by harmful preconceptions.

Burrell cites slave owners, mass media, J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI and commercial advertisers as historic purveyors of the black inferiority myth — each with its own motives. True to his advertising roots, he presents the existing propaganda in the form of charts and his suggested solutions under bold headings.

Exercise and nutrition should be commended in the black community. Purchases of bling should not be a salve for emotional wounds or a substitute for status. Community leaders and clergy should be held more accountable. Once black Americans are aware of the hidden agenda behind their conditioning, stereotypical habits will become unattractive.

“Brainwashed” is a provocative read. Burrell believes the only way to eliminate self-destructive behavior is to create a national campaign of positive messaging. He hopes this initiative will be both a counterattack and his legacy.

In the film “The Godfather,” mafia leader Don Zaluchi is a minority of one, opposed to illegal narcotics trafficking because drug abuse destroys families. When The Don voices his objections at a national meeting of mafia leaders, he offers the condition that the dope distribution be limited to the colored community, on the grounds, “They’re animals anyway, so let them lose their souls.”

In Burrell’s ideal world, there would be no demand for the mobsters’ illicit supply.

Bijan C. Bayne is a frequent contributor to the Bay State Banner.