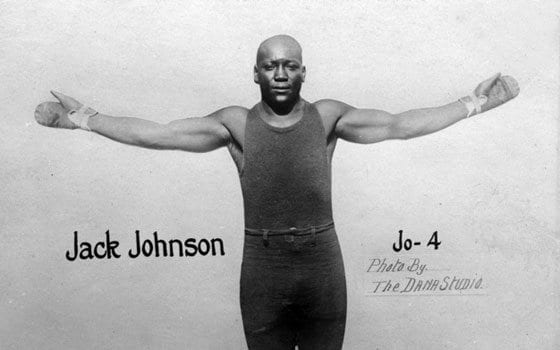

How Jack Johnson became boxing’s first black heavyweight world champion

The news from Down Under reached New York on Christmas night, speeding there in just 24 minutes through the modern miracles of land and sea cables.

Most Americans got the word the next morning in their newspapers. Just as well, because the news was sobering to a nation still divided by race less than a half-century after the end of the Civil War.

A black man was the heavyweight champion of the world.

As the year 1908 was drawing to an end, and Jack Johnson reigned supreme. After years of chasing reluctant white champions for a fight, he gave Tommy Burns a beating in Australia that reverberated half a world away.

Almost immediately, a frantic search began to find someone to wrest the crown from his freshly shaved head. Just as quickly it settled on Jim Jeffries, the former champion who had retired unbeaten to his California farm four years earlier.

“Jim Jeffries must emerge from his alfalfa farm and remove the golden smile from Jack Johnson’s face,” author Jack London wrote.

It wouldn’t be easy. Jeffries had ballooned to over 300 pounds in retirement and was a reluctant warrior, at best. He had little interest in fighting again, and even less interest in bearing the weight of an entire race on his broad shoulders against a champion who flouted society’s mores with his love of fast cars and white women.

Jeffries also knew something most of white America refused to acknowledge: Johnson was not only a fine physical specimen, but possessed perhaps the finest skills of any heavyweight since the Marquess of Queensbury rules turned boxing into a somewhat respectable sport.

Still, the drumbeat intensified. Promoters dangled riches in front of Jeffries, and newspapers campaigned for him to save his race.

The Chicago Tribune ran a cartoon in April 1909 of a little girl in blond curls asking, “Please Mr. Jeffries, are you going to fight Mr. Johnson?”

Finally, Jeffries acquiesced. The former champion, his hairline receding at the age of 34, was in.

They would meet on July 4, 1910, in a scheduled 45-rounder that was immediately dubbed the Fight of the Century. For once, it wasn’t just hype, because a lot more was at stake than just the heavyweight title.

The fight was to take place in San Francisco, until California’s governor stepped in with less than three weeks to go. Boxing was still banned in many states, and church groups had pressured him to stop it on moral and religious grounds.

Politicians and civic leaders in the dusty, high desert town of Reno had no such qualms. They quickly convinced promoter Tex Rickard they could host the fight and could quickly build a 20,000-seat arena on the eastern edge of town.

And so, Rickard and the fighters boarded a train for Nevada.

Soon they would share a 22-by-22 stretch of canvas for a moment so big it intrigues historians to this day. There would be other big fights, other big sporting events, but none that could match the Fight of the Century for what it meant to America 100 years ago and for many years afterward.

Two days before the fight, one newspaper account described Johnson as carefree and cool, saying he appeared to have taken his preparations for the fight seriously.

Jeffries, meanwhile, was reported to be in shape, though the correspondent said the challenger “undoubtedly possesses the worrying qualities of the white race.”

The same day, New York City politician Big Tim Sullivan arrived to declare himself as the official stakeholder for the fight. He would hold the $101,000 purse, which would be split 75-25 in the winner’s favor. For the first time, the two fighters would also get $50,000 each for movie rights.

The fight

The day the sporting world had been waiting for was a hot one, and there was no shade in the arena from the blistering sun. Workmen were still busy sawing and hammering on the temporary arena and two hoses were stretched inside in case all the fresh pine caught fire.

The arena, built in just two weeks, had 18,000 seats ranging from $10 to $50 at ringside. Another 2,000 people would pay $5 for standing-room-only spots.

With racial tensions on edge, there would be no liquor sold or allowed in the arena, and no drunks allowed inside. Women could come, one paper said, as long as they could put up with the heat.

As fight time neared, a line of people a half-mile long waited to get in the single entrance. Included were several hundred women, who would be seated in their own private section, where they draped pieces of cloth together for a makeshift sun shield.

Guns were checked at the gate, and fans were searched for cameras. A brass band played to warm up the crowd.

The fight started late, causing rumors to sweep through the crowd that Johnson had chickened out. Finally, at 2:31 p.m., he walked into the ring wearing a black and white striped robe, his head freshly shaved. Jeffries followed a few minutes later in street clothes under a fan his wife insisted he use as a sun shield.

The fight finally went off at 2:44 p.m., with both men smiling at each other as they made their way to the center of the ring, though Jeffries refused to shake Johnson’s hand. The first round was uneventful, but it didn’t take long to realize that Jeffries would have trouble imposing his will on the younger champion, as he had done with all his previous opponents.

Johnson used counterpunching early to stop the onslaughts and, as the rounds went on, he began landing punches almost at will to the challenger’s reddened face. Corbett roamed about at ringside shouting insults at Johnson and imploring Jeffries on, but Johnson was just too slick.

Age and inactivity were taking their toll on Jeffries as the fight progressed. By the 13th round the challenger’s nose was broken, his eyes were nearly swollen shut and he was gasping for air. Years later, Johnson would write that he knew the fight was over in the fourth round when he landed a left uppercut that seemed to paralyze the side of Jeffries’ face.

“I knew what that look meant,” he said. “The old ship was sinking.”

The end came in the 15th round when Jeffries, his face puffy and bloody, went down for the first time in his career from a flurry of punches. He was able to get up at the count of nine, but Johnson sent him through the ropes with a right hand to the jaw. His seconds and reporters had to help him back into the ring.

Jeffries then staggered across the canvas where a combination put him down for the last time. His seconds jumped into the ring to stop the fight, even though there was no doubt Jeffries was not getting up.

The Associated Press reported the outcome:

“John Arthur Johnson, a Texas Negro, the son of an American slave, tonight is the heavyweight champion of the world.”

John L. Sullivan wrote for the Times that there had never been a championship contest so one-sided. Even more impressive, he said, was how it was done.

“He played fairly at all times and fought fairly,” he said.

In Chicago, some 10,000 people, mostly white, gathered outside the Tribune building to listen to a man on a megaphone read bulletins from the fight. Black fans, meanwhile, went to the Pekin theater where Johnson’s mother, Mrs. Tiny Johnson, got updates on the fights.

Another 30,000 people stood in Times Square on the nation’s birthday to watch the newspaper’s new automated device spit out the news. They cheered when the first bulletin announced a Jeffries left to the head, but quickly went quiet as it became apparent the fight was not going the white man’s way.

“It was the greatest bulletin service I have ever seen,” police inspector Richard Walsh said. “But I do wish it could have told a more pleasant story.”

So did the crowd in Reno, which wasted no time exiting the arena and little more in getting out of town.

The aftermath

Things quickly got ugly as news flashed around the country on this Fourth of July that a black boxer had not only beaten the “great white hope,” — a label some have attributed to London — but had given him a beating in the process.

Some black fans decided to celebrate publicly. Some whites decided that wasn’t such a good idea.

In New Orleans, a black man who shouted “Hurrah for Johnson” was severely beaten by whites before police came to his rescue, and in Houston, a black man named Charles Williams had his throat slashed ear to ear by a white man for cheering for Johnson on a streetcar.

A mob of 200 whites chased blacks off the sidewalks in Washington, and in Cincinnati several hundred whites ran after a black who made a comment they found offensive. In Clarksburg, W. Va., whites were so angry at the triumphant shouting of blacks that they formed a 1,000-man posse to chase all blacks off the streets, including one who was led about with a rope around his neck.

Scattered rioting occurred in most major cities, and in some cities blacks fought with blacks.

The next day the Chicago Daily Tribune counted at least 11 dead around the country, with scores of others injured. The New York Times listed 10 deaths.

In a day of new technology, there was another issue. Promoters had planned to show films of the fight in theaters, but a black man winning complicated things.

The powerful Christian Endeavor Society campaigned for a ban and mayors in Cincinnati, Atlanta and Boston quickly agreed. The police chief in Washington also banned the films, fearing “the display of pictures would affect the minds of children and also renew the hostile feeling on the part of many white men.”

The Pastors Federation in Washington went further, asking authorities not to permit Johnson in the city limits.

Former President Theodore Roosevelt even weighed in, writing in Outlook magazine that he hoped people were so enraged that there would never be another prize fight in the United States.

Johnson left Reno on the evening train hours after the fight, heading home to Chicago where a big celebration was planned.

White America wasn’t as welcoming. The realization that not only was there a black heavyweight champion, but one with the skills to be champion a long time was unsettling.

It hardly mattered that outside the ring, Johnson was a man of culture who played music on his Renaissance-era viol — a type of violin — was conversant in several languages and often read novels in French. They saw only the public side of Johnson, that of a high-flying flamboyant champion who refused to live by the unwritten rules of society.

Johnson wouldn’t fight for another two years and, soon afterward, was arrested on trumped-up charges of violating the Mann Act by transporting women across state lines for immoral purposes.

He was convicted and sentenced to a year and a day in prison, but skipped bail and left the country. Johnson would lose his heavyweight title in 1915 to Jess Willard in Havana and would fight in Mexico and Spain before returning to serve his sentence in 1920.

Never repentant about his ways, Johnson was still an attraction in his later years, fighting sporadically and putting on exhibitions. He died angry, crashing his Lincoln Zephyr at high speed on a North Carolina road after being refused service at a diner in 1946.

Jeffries, meanwhile, returned to the alfalfa ranch and trained fighters until his death in 1953.

It would be 27 more years before Joe Louis beat James Braddock and a black man became heavyweight champion again.