A generation before baseball’s steroid era, two men from Alabama stalked Babe Ruth’s lifetime home run mark.

This year, biographies of both men — Willie Mays and Henry Aaron — have occupied the literary baseball stage. As with the legendary ballplayers, comparison is a game of spherical objects — apples and oranges.

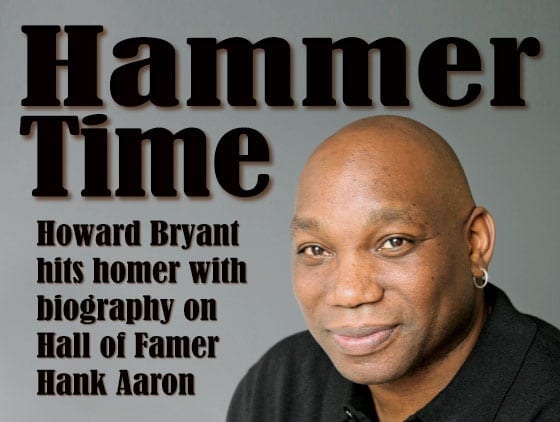

“The Last Hero: A Life of Henry Aaron” is the latest effort by Bostonian Howard Bryant, the former Boston Herald sports columnist who made his bones with “Shut Out: A Story of Race and Baseball in Boston” (Beacon Press 2002).

His examination of Aaron is the best baseball biography to come along in years, a work that fuses the storytelling acumen of a David Halberstam with the sensitivity for race and sport embodied by writers such as Dave Zirin and William Rhoden.

From Aaron’s humble beginnings in Mobile, Ala., to fly-on-the-wall locker room recollections of the pennant winning Milwaukee Braves of the late 1950s, Bryant brings a quiet American hero to life as never before.

One major distinction between “The Last Hero” and James Hirsch’s “Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend” is that many baseball fans are already acquainted with Mays, a media darling from the outset of his career.

The perception is that Aaron labored largely in Mays’ shadow, a notion that Bryant contests.

Bryant quotes opposing managers and journalists who generously credited Aaron early on, while Mays wowed fans and scribes not just with his consummate skills, but also his charisma. Sports reporters found young Aaron distant, and his distrust of them grew when they quoted him in phonetic Negro dialect he did not use.

Teammates also felt the young slugger was difficult to know, a boundary enhanced by the fact Aaron was not a hearty drinker as were other Braves stars.

Henry Aaron was born to Herbert and Stella Aaron on Feb. 5, 1934. His father was a riveter in a Mobile shipyard; his mother a housewife. The Aarons and what would become six children moved four times in 13 years. To make ends meet, Herbert also worked as a boilermaker assistant, and a minesweeper for the U.S. Navy. When the family settled into a section of the city called “Down the Bay,” there were white and colored families on their street.

But segregation still dominated the social order. A young Henry watched his father surrender his place in line at the general store to white customers. His mother sometimes heard Ku Klux Klansmen marching down the street, recognizable by their drumbeat.

Despite those social discomforts, young Henry’s childhood was consumed with creek fishing and baseball. His obsession with the game began when he was 13, when Jackie Robinson debuted with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Aaron patterned himself after Robinson and he never strayed from an aspiration to play major league baseball.

Mobile was a baseball town; it produced “Satchel” Paige and Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe of Negro League repute, big leaguers Billy Williams, Willie McCovey and Tommie Agee in Aaron’s footsteps, and white pitchers Milt and Frank Bolling.

Henry’s path to “The Show” was dotted with stints with the semi-pro Pritchett Athletics (for two dollars a game), and his celebrated apprenticeship with the Indianapolis Clowns.

When the prospect signed with the Boston Braves in June of 1952, he had never been farther from Mobile than his father’s hometown of Camden, Ala. — and that was a trip made on horseback.

Henry’s first minor league manager was Alabamian Bill Adair, whose scouting report on him read, “No one can guess his IQ because he gives you nothing to go on. He sleeps too much and looks lazy, but he isn’t … as a hitter he has everything in this world.”

Aaron married Jacksonville native Barbara Lucas in 1953, and by 1954, he was a starting outfielder for the Milwaukee Braves. Bryant excels at recounting the group dynamics of the Braves’ clubhouse, dominated by hard living Eddie Mathews, intellectual World War II veteran Warren Spahn and bitter Southerner Joe Adcock.

All were stars, none close to the younger Aaron. In contemporary articles, Aaron is generally portrayed as a quick-wristed, dim-witted Negro phenom — a slow moving, illiterate batter savant.

A 1956 “Saturday Evening Post” profile by Furman Bisher helped cement this image. Of a batting slump, Bisher quoted Aaron having said, “I coming out of it.” When asked about an alleged statement to teammate Joe Andrews, Bisher’s Henry responded, “I liable to tell Joe Andrews anything.”

As he matured, Aaron would fight the stereotype by reading James Baldwin and befriending Jim Brown.

He and his wife publicly balked at the Milwaukee franchise’s impending move to segregated Atlanta in the mid-1960s, and in October 1965, he was the subject of a “SPORT” magazine feature on the prospects of a Negro manager in the big leagues, titled “I Could Do The Job.”

Braves’ officials attributed their superstar’s outspokenness not to the changing times, but to his wife Barbara, whom they considered ill-tempered.

Bryant astutely sources national media, Milwaukee and Atlanta press, former teammates and even batboys, to present a three-dimensional Aaron. Unlike many biographers, he references “SPORT” magazine, which had a more investigative edge than “Sports Illustrated.”

The American and local racial backdrop is ever present. In addition, Bryant provides the color and tension of National League pennant races — and Aaron’s pursuit of the all-time home run record.

The narrative follows a thoughtful, misunderstood player, to his emergence as the team leader in whom the parents of young black Braves players would entrust their sons.

The author demonstrates that Mays always resented Aaron, taunting him in front of the press and supplying back-handed flattery when it became clear “The Hammer” would shatter Ruth’s standard.

For readers eager to know the man behind the numbers and the footage, Bryant hits one out of the park.

Bijan C. Bayne is a frequent contributor to The Bay State Banner.