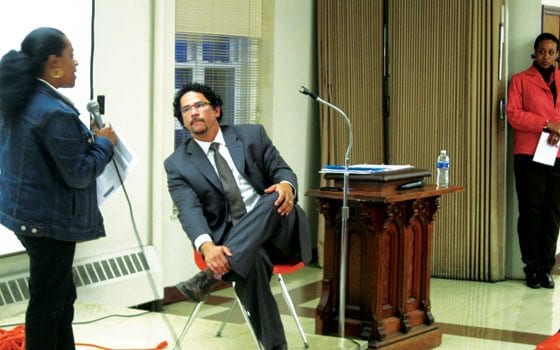

If there was one thing that united the parents, students, teachers and other education activists who came to the 12th Baptist Church to meet with Alberto Retana, the director of community outreach for the U.S. Department of Education, it was the desire for change.

Retana, as is implied by his job title, wants greater parental involvement in the schools. Many of the parents want better schools and a better school system. The students’ demands may sometimes seem more pedestrian — but at the same time, more poignant.

John D. O’Bryant School of Mathematics and Science student Khalita Stafford’s question underscored the nuts-and-bolts challenges of education reform.

“How do we ensure high-performing schools get enough resources?” she asked. “We just got our math books in January, and when we got them, the pages were ripped. We’re a math school.”

Stafford, who works with the Boston Youth Organizing Project, said she would also like to make sure students at her school have a place to sit.

“There aren’t enough chairs in our classrooms,” she said during the meeting earlier this month.

Retana, invited to meet with Boston parents by the Boston Parent Organizing Network (BPON), is touring school districts throughout the United States to solicit input on the department’s school reform agenda.

While funding for local schools comes from state taxes and local property taxes, the federal government provides competitive grants to school districts and sets national education standards states must comply with.

Massachusetts last month lost out on its application for federal Race to the Top funding, which would have brought in an additional $230 million.

More disturbing is that Boston has 12 schools that the state has declared “underperforming.” That qualifies them for federal aid, but also requires tough interventions from the school district — which could include anything from mandated retraining of teachers to firing of teachers and principals to turning the schools into charter schools.

The implementation of the turnaround plans for the schools might not be as easy as envisioned, however. BPON parent activist Regina Logan asked Retana how to prevent fired teachers from returning to the schools that dismissed them.

“From the federal level, we can’t prevent teachers from being re-hired,” he said. “It’s a contract issue between your city and the labor union.”

But oftentimes, when those contracts are hammered out, parents are left out of the process, Retana noted.

“Your voice is missing from the debate,” he said.

Before joining the Obama administration last year, Retana worked on parent involvement in the Los Angeles school system as a community organizer with the Community Coalition, an organization active in South Central LA.

In his opening remarks, he spoke about the importance of independent, community-based groups’ organizing around educational issues.

“If you’re not involved, decisions will be made without you,” he said.

Retana seems to have retained some of his outsider’s view, making few apologies for his department’s shortcomings.

When Nicolasa Lopez asked what the department is doing to make sure the children of undocumented immigrants don’t drop out of school, Retana’s answer was blunt. “Not enough,” he said. “We need to do more.”

BPON Executive Director Myriam Ortiz said the meeting gave the parents a clear indication that their involvement can produce change in Obama administration policies.

“Alberto was very receptive and, because of his background, he was very respectful,” she said. “He didn’t appear as just another bureaucrat from Washington telling us what to do.”

A delegation of BPON parents will travel to Washington May 6 to meet with Obama administration officials about reforming the No Child Left Behind Act, Ortiz said.

“The component of parent engagement in No Child Left Behind isn’t very strong,” she said. “Now there’s another window of opportunity to change it.”