Author: Caitlin Yoshiko BuysseDespite consumer confusion, federal government slow to regulate misleading labels

Author: Caitlin Yoshiko BuysseDespite consumer confusion, federal government slow to regulate misleading labels

As obesity rates skyrocket, Americans are increasingly concerned with proper nutrition — and are looking to nutrition labels for guidance on what to eat.

But nutrition labels and front-of-the-package advertising are frequently misleading — if not outright deceptive — making healthy eating a tricky task.

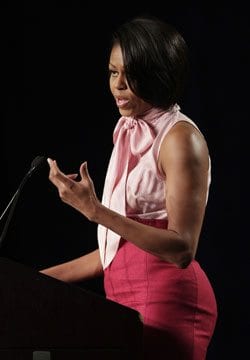

The problem has attracted the attention of Michelle Obama, who promptly made them a core piece of her “Let’s Move” campaign against childhood obesity. The first lady has said that she hopes to not only educate families on how to read labels, but also push the food industry to change the confusing and misleading ones.

“Parents shouldn’t need a magnifying glass and a calculator to make healthy choices for their kids,” Obama said in a speech to the Grocery Manufacturers Association earlier this year. “We need you not just to tweak around the edges, but to entirely rethink . . . the information that you provide about these products.”

As it is now, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) oversee nutrition labeling on foods — the USDA covers meat and poultry, while the FDA manages everything else.

Their policies are intended to guarantee accurate labeling on all food products through a system of pre-market screening, product evaluations and disciplining companies that fail to meet regulation standards. But a new report by the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI), an independent consumer advocacy organization, details many out-of-date policies and spotty records of enforcement.

For instance, the FDA requires a rigorous approval process — involving substantial scientific evidence and a 540-day waiting period — before a food company can advertise health claims about its product. “May help reduce the risk of heart disease” is an example of this type of claim.

But food companies regularly use semantics to easily circumvent FDA policies. Advertising with the phrase, “Helps maintain a healthy heart” requires no FDA approval and can be used regardless of the product’s nutritional content.

Similarly, while the FDA regulates claims about nutrients such as cholesterol, sodium and fiber, no policies exist to monitor claims about ingredients like whole wheat, fruits and vegetables.

As such, juices, cereals and snacks can claim, “contains whole wheat” or “made with real fruit” on the front of their packages irrespective of their actual content.

Sugar is another poorly regulated ingredient. While the FDA imposes regulations on product claims of “sugar-free,” “reduced sugar” and “no added sugar,” none exist for the claim of “low-sugar.”

Moreover, nutrition labels are not required to disclose amounts of added or refined sugars — only natural ones. As a result, many consumers are left in the dark about the actual amount of sugar their soda, candy or cereal contains.

In yet another loophole, food companies can advertise products as “fat-free” or “low-fat,” even if they contain high amounts of sugar — leading the consumer to believe that large quantities can be eaten without gaining weight. Similarly, many companies advertise “trans fat-free” products high in saturated fat.

The USDA and FDA also regulate “organic” and “natural” claims on food products. The USDA operates a strict certification process for organic foods, which sets standards for the living conditions of livestock and the use of hormones, antibiotics, fertilizers and pesticides, among other things.

While this process has offered some clarity on the quality of foods, many companies advertise their products as “organic” even in the absence of official certification.

The “natural” claim is even murkier. The FDA has never issued an official definition of “natural,” so foods and beverages containing high-fructose corn syrup and artificial coloring and flavoring are frequently advertised as “natural.” The USDA has a similarly unclear standard for “natural” meat and poultry, thus enabling food companies to advertise “natural” products that contain added broth, salt or sugar.

While consumers and Congress have consistently pushed the USDA and FDA for tighter regulation and enforcement on food labels, these institutions have shown little willingness to provide them.

As the Government Accountability Office (GAO), a nonpartisan watchdog agency for Congress, recently stated, the FDA “has little assurance that companies comply with food labeling laws and regulations for, among other things, preventing false or misleading labeling.”

The FDA’s shortcomings, a 2008 report explained, include not keeping pace with the growing number of food companies, limited testing of label accuracy, few disciplinary actions to enforce policy and failure to track violations.

In the meantime, food companies are making big profits. Foods labeled “natural” brought in $22.3 billion in sales in 2008, up 10 percent from the previous year, and up 34 percent in the past four years.

In the same year, organics generated $4.9 billion in sales, up 16 percent from the previous year, and up an astounding 134 percent in the past four.

The sales of foods bearing health claims on their labels have also risen dramatically in the past four years. Americans purchase nearly $8 billion worth of foods labeled “fat-free” (including saturated and trans fats) each year — representing a 169 percent increase in the past four years. And well over a third of all snack foods purchased bear the label “trans fat-free” or “saturated fat-free.”

Under the Obama administration, the federal government has shown some signs of improvement. Recently, the FDA notified 17 major food companies that they had violated federal law by placing false and misleading labels on the front of their packaging.