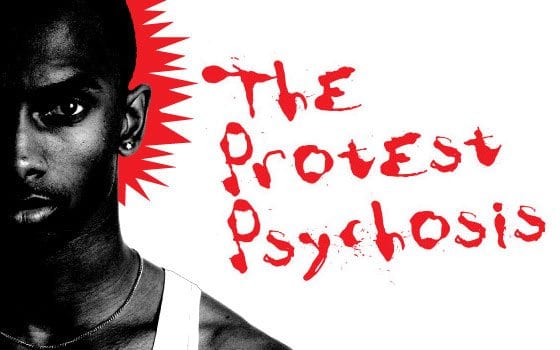

In his latest book, author Jonathan M. Metzl explores how black anger became diagnosed as schizophrenia

| “The Protest Psychosis: How Schizophrenia Became a Black Disease,” Jonathan M. Metzl, Beacon, 288 pp., $24.95. |

After Cassius Clay famously performed during the weigh-in for his first championship bout with Sonny Liston in 1964, fight physicians thought the brash 22-year-old really was crazy.

An 8-to-1 underdog, Clay repeatedly called Liston a “bear” and “ugly” and boasted about how he deserved to be world champion because he was “pretty” and “faster” and “better.” It was more than just talk. According to one observer, Clay looked “like he was having a seizure…all gathered up in his own hysteria, totally out of control.”

Though Clay would later say he was using “psychological warfare” to rattle one of boxing’s most feared intimidators, the boxing commission’s doctor had a completely different diagnosis.

For starters, Dr. Alexander Robbins explained at the time, Clay’s blood pressure had skyrocketed shortly after the weigh-in from a normal rate of 54 beats per minute to 110, more than twice his norm. And this was after the actual weigh-in scene. Robbins further announced that Clay was “emotionally unbalanced, scared to death, and liable to crack up before he enters the ring.”

Of course, Dr. Robbins’ diagnosis was dead wrong: Clay went on to shock the world and defeated Liston when he refused to answer the bell after the sixth round. Clay said he knew what he doing the whole time. He told the media that his histrionics were contrived to frighten Liston — much like a crazy man could scare a bully.

For decades, black people, particularly men, have resorted to a facade of mental illness to dupe oppressors, avoid military service — and in Clay’s case, psyche-out a competitor. But the role of acting “crazy,” long-considered to be a survival tool for those at the social and economic bottom, was used to further demonize African American males.

In “The Protest Psychosis,” Jonathan M. Metzl, a University of Michigan psychiatry and women’s studies professor, argues that American society — and mental health institutions in particular — disproportionately offered schizophrenia as a diagnosis on politicized and outspoken black males during the turbulent 1960s.

Metzl explores the changing demographics and diagnoses of the Ionia State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in Ionia, Mich. Before 1955, the average annual population consisted of 122 whites and 17 Negroes. By the late 1960s, the population was about 60 percent black. By 1977, the former asylum had become Riverside Correctional Facility — a prison.

Derived from the Greek words for “split” and “mind,” schizophrenia has been long associated with aggressiveness, projection and violent tendencies. Metzl retraces Western European and American distinctions in this type of mental disorder, starting with the work of Paul Eugen Bleuler, the Swiss psychiatrist who coined “schizophrenia” as a diagnosis.

Metzl also examines what became the industry standard, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Disorders (DSM-II). Published in 1968 by the American Psychiatric Association, the 134-page manual listed 182 mental health disorders and was widely used throughout the industry.

It is within that context of psychiatric standards and cultural norms that Metzl illustrates how Ionia staff, law enforcement and pop culture bought into stereotypes concerning angry black men.

For this assertion, Metzl relies on case studies, file letters pleading for empathy from family members of black patients, and mainstream America’s evolving fears about black power and urban unrest.

Such perceptions, Metzl argues, affected not only Ionia’s racial makeup, but eventually, its architecture. Gothic stone buildings, man-made waterways and verdant recreation spaces gave way to barbed wire and uniform, foreboding edifices.

White women, who made up 26 percent of the asylum’s population in 1941, were removed from the equation almost completely. There were less than 30 housed in the asylum in 1972, a far cry from the sixties when they numbered several hundred.

During this period, Metzl writes, neither black men nor white women in Michigan changed bio-chemically — society did. Where schizophrenia had once largely been the province of painters and poetic geniuses — and beleaguered housewives-turned-apathetic — the 1968 DSM-II profile led to over-diagnosis of schizophrenia in black men, including some who Metzl shows were victims of police brutality, beatings by white bigots, or embraced Black Nationalist philosophies.

“The Protest Psychosis” does not lean solely on the old Ionia case histories to present its thesis. Images depict a 1968 ad for the anti-psychotic drug Haldol, in which a fist-shaking figure resembling James Brown appears under the caption “Assaultive and Belligerent?”

Ads for Stelazine, another anti-anxiety medication, portrayed tribal masks. Metzl recounts the 1963 cult film classic “Shock Corridor” in which a Negro activist portrayed by Hari Rhodes is committed to a mental institution, where he incites a “race riot” on his ward.

In movies concerning white schizophrenia patients, such as 1948’s “The Snake Pit” (starring Olivia deHavilland) and 2001’s “A Beautiful Mind,” the main character in the former is a “beautiful, happily married writer” — a nonviolent woman whose breakdown provides the tipping point for an expose of archaic asylum conditions. In “A Beautiful Mind,” the protagonist is not a ranting race protestor, but a gifted Nobel Prize-winning economist and mathematician.

From the black viewpoint, activists such as Stokely Carmichael, the Rev. Wyatt Tee Walker, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and most famously, Dr. W.E.B. DuBois, argued that a double-mindedness — or “twoness” — was a necessary state of survival.

Others such as Franz Fanon, a psychiatrist and influential author in the field of post-colonial studies, maintained that racist societies were, in themselves, schizophrenic. On the one hand, they preached democracy; but, on the other, they practiced frequent and often violent discrimination. Born in 1925 in Martinique, a former French colony, Fanon published his first book in 1952, “Black Skin, White Masks,” an analysis of the effect of colonial subjugation on humanity.

In his book, Metzl finds the psychological community generally overlooked such viewpoints in both its broad and individual assessments of black males ordered into the mental health system by judges and prison wardens.

Thus 88 percent of black Ionia admittees after 1960 were diagnosed as schizophrenic, compared to only 44.6 of the white men.

This trend occurred at a time when asylums were increasingly under attack, if not for the actual questionable treatment of patients, then certainly for the science used to treat and manage their behaviors.

In 1963, for instance, President Kennedy signed the Community Health Act, calling in part for the deinstitutionalization of mental health patients. Over the next 15 years, the census of state and county mental hospitals decreased by about two-thirds. In their place emerged prisons. While a largely white segment of former mental patients suddenly wandered streets and filled shelters, more and more black men were labeled dangerous schizophrenics who resisted authority figures.

While Metzl does not doubt that some of these men needed help, he quotes studies in which, even today, black men (some of whom may suffer from depression) are four times as likely to be categorized as schizophrenic as their white peers are. He also cites the work of black (and some white) psychologists and scholars who pioneered research on analytical discrepancies.

Among those authors are R.D. Laing, David Cooper, Melissa Harris-Lacewell (the latter on the lack of treatment initiatives that consider black women), and psychiatrists William Grier and Price Cobbs’ seminal work “Black Rage.”

“The Protest Psychosis” is an indictment not so much of an evolving science. After all, the staff at Ionia — as well as other psychiatrists across the U.S. — were merely adhering to industry standards. But Metzl offers little defense for a mainstream culture that projected its racial schizophrenia onto those considered inferior and scary at the same time, the very definition of having a mixed and dangerous mind.

Bijan C. Bayne is a cultural critic and frequent contributor to the Bay State Banner.