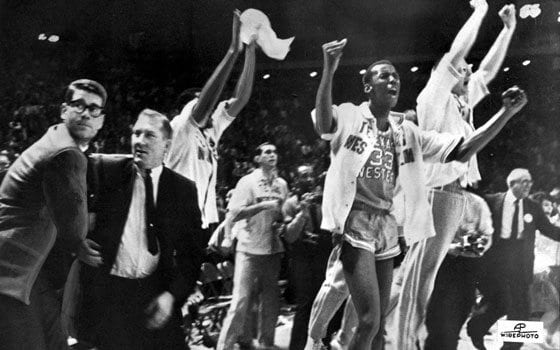

In this March 19, 1966 file photo, Texas Western College head basketball coach Don Haskins, second from left, and players celebrate after winning the 1966 NCAA basketball championship in College Park, Md. (AP Photo)

| Members of the 1966 NCAA Championship Texas Western team pose for their picture during a media availability at the team’s induction into the Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, Mass., Friday morning, Sept. 7, 2007. (AP Photo/Stephan Savoia) |

EL PASO, Texas — Forty minutes of basketball produced 40,000 pieces of hate mail.

The world in 1966 was not ready to accept Texas Western’s defeat of Kentucky for the NCAA basketball championship. A team with five black starters jolted many people, and its triumph over an all-white bastion of Southern basketball elevated the game to a broader discussion about segregation and race relations.

In the beginning, the outcome motivated all those venomous letters that found their way to the mailbox of Texas Western coach Don Haskins.

Today, the game remains one of the most-discussed sporting events in history. But the conversation has changed, just as it did after Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color line in 1947 and after Muhammad Ali refused induction to the Army in 1966 by famously declaring, “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong.”

Texas Western, now the University of Texas at El Paso, went down in history as the team that changed recruiting and opened doors for black students at schools that once excluded them.

Nevil Shed and Dave Lattin, two members of the 1966 team, say no game could have been better. Both were 22 when Texas Western won the national championship. They are 66 now, and have had most of a lifetime to enjoy it.

“I’ve been on a Wheaties box and I’ve met the president because of that game and the history it made,” Shed said in a recent interview from his home in San Antonio.

He also has been portrayed, inaccurately in parts, in the most high-profile account of the championship season. The movie “Glory Road” contained a fictitious scene in which thugs dunk Shed in a toilet. Sure, it was Hollywood embellishment at its worst, but it did not bother Shed.

“The point is that a lot of people were dissatisfied because of our success,” said Shed, who at 6 feet 8 inches and 185 pounds, was known as “The Shadow.” “We took their negative energy and turned it into positive action.”

Lattin, an exceptional leaper and thunderous dunker, got far less attention in the movie than Shed. He spent $40,000 in 2006 to publish his own book about the championship team, “Slam Dunk to Glory.”

As a high-school star in Houston, Lattin averaged 29 points, 19 rebounds and 13 blocked shots a game for a state championship team.

“I could fly,” he said.

Hundreds of colleges recruited him, but schools such as Kentucky were not interested. Lattin started his college career at Tennessee State, a historic black school in Nashville. His hometown school, the University of Houston, tepidly recruited him, wanting to bring in a black football player before a black basketball player, Lattin said.

After a short, unhappy stay at Tennessee State, he transferred to Texas Western. One of his most vivid recollections is that Haskins, so stern and explosive, never yelled at him. “We tolerated each other, I guess,” Lattin said of Haskins. “He kept a distance. No one ever talked to him.

“He yelled a lot, but he never yelled at me. There was no reason. I worked hard, and you could get much more out of me by just talking to me.”

Haskins was nicknamed “The Bear,” and Shed brought out his ferocity.

“Nevil, he’d jump to the moon when Haskins yelled,” Lattin said.

“Yes, that’s true,” Shed said. “I was his whippin’ dog. I guess I have to wait to go to heaven to see why. But he never killed my spirit. He never cursed at me, and he never killed my spirit.”

Once, though, Haskins became so exasperated with Shed that he said he played like a girl. Haskins told assistant coach Moe Iba to “put him in a skirt.”

Despite such tirades, Shed developed great affection for Haskins, calling him the most influential person in his life except for his parents.

Shed visits El Paso three or four times a year. Those who remember the magic of 1966 are always close by.

“Before I get to the rental car at the airport, I will hear people calling to me, ‘Shadow! Shadow!’ They still remember. Those are the things I’m going to take to my grave. I thank God for my mother and my father, and I thank God for Don Haskins.”

Lattin had a substantial basketball career after leaving Texas Western. He played professionally in the NBA and in the old American Basketball Association, and he had two tours with the Harlem Globetrotters. He is in the wholesale liquor business in Houston.

Lattin did not get a degree at Texas Western, but went back to school to study broadcast journalism at Texas Southern, where he graduated in 1998.

Looking back at the game against Kentucky, Lattin said he was certain Haskins wanted to make a statement about race by using only black players against the Wildcats.

“Absolutely, it was intentional,” Lattin said. “About 3 o’clock, after the pregame meal, Haskins gave us his talk. He said, ‘It’s up to you.’ That was it. No chalkboard.”

For all the racial tension of 1966, basketball players did not talk on the floor the way they do now.

Shed said no words were exchanged between the Kentucky players and the Miners. Lattin said Kentucky’s big stars, Pat Riley and Louie Dampier, were silent. But one Kentucky player spoke up to pay him a compliment during the second half.

Lattin got loose and slammed the ball in. Kentucky’s Thad Jaracz looked at him and said, “Nice dunk.”

That was it. No trash talking. No taunting. The final score was Texas Western 72, Kentucky 65.

Shed and Lattin said they played that March night for victory, never considering that the game would become a symbol for social change.

Shed, now a motivational speaker, gave his first talk at the University of Kentucky. The school that would not recruit black players in the 1960s won a national championship with a black coach, Tubby Smith, in 1998.

The world had changed, and perhaps it happened more quickly because of the Miners’ triumph.

Lattin said the impact of Texas Western felling a giant like Kentucky was immediate.

“What really happened was this: All the schools that wouldn’t let African-American kids in had to review their policies. We got them to open the door for all the kids.”

El Paso Times