SCOTTSBORO, Ala. — The very name of this Alabama city has stood for racial injustice for almost 80 years.

Nine young black men went on trial in Scottsboro in 1931 on charges of raping two white women in a case that made headlines worldwide. The defendants — eight of whom were sentenced to die — came to be known as “The Scottsboro Boys” and the charges were revealed as a sham.

Now, four generations later, Scottsboro is acknowledging its painful past.

With biracial support in a Tennessee River community that is 91 percent white, organizers this month opened a museum documenting the infamous rape prosecution and its aftermath.

The museum isn’t large or fancy — it’s located in an old African American church near the city’s main attraction, a store that sells clothes, wrenches, iPods and other items pulled from unclaimed airline baggage. Its operating hours, for now at least, are spotty.

But the opening of The Scottsboro Boys Museum and Cultural Center helps fill a hole in the historical narrative of a city that seemingly went out of its way for decades to ignore an ugly stain.

“The history of the case is rich. People know, ‘Those nine black boys raped those white women.’ But people don’t know about the case, what really happened,” said Sheila Washington, a black woman who headed a push for the museum.

Mayor Melvin Potter said some residents would still rather forget the whole episode. To this day, some go to lengths to point out that the nine men were arrested in another town, Paint Rock, and everybody involved was from another county. Scottsboro got a bad rap, they say.

But Potter, who is white, said the museum’s time has come.

“It’s like they say: If you don’t remember history there’s a chance you can repeat it,” he said.

With the nation gripped by the Great Depression after the stock market crash of 1929, people hopped freight trains to travel from one city to the next. A fight broke out between blacks and whites on a train in Jackson County on March 25, 1931.

Trying to avoid arrest, two women who were on the train falsely accused nine young black men of raping them. It was the worst possible allegation in a region where whites were trying to assert supremacy just 66 years after the end of the Civil War.

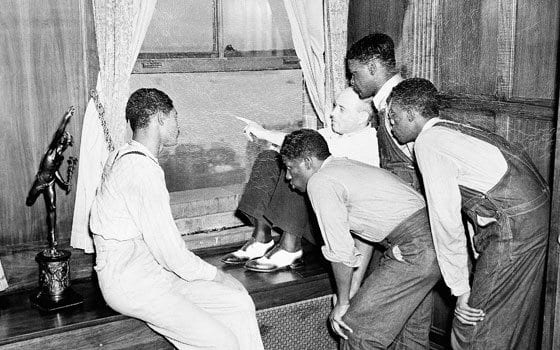

The blacks, ranging in age from 13 to 20, were shackled and taken to Scottsboro, where an angry white mob gathered for their trials before all-white juries just two weeks after the arrests. Eight of the nine were convicted and sentenced to death; jurors couldn’t reach a verdict for the youngest defendant.

The convictions shocked the nation: thousands of people marched in protest in Harlem and the case was covered heavily by news magazines of the day. Books, plays and poems were written about the plight of the defendants.

There were years of appeals — some successful, as one of the women recanted, saying their claim was a lie — and more trials. All the men were eventually freed from jail without any executions. Then-Gov. George C. Wallace pardoned the last surviving defendant, Clarence Norris, in 1976. Norris died in 1989.

The case set important legal precedents that still resonate decades later, including Supreme Court rulings that guaranteed the right to effective counsel and barred the practice of eliminating all blacks from jury service.

But in Scottsboro, the case soon faded into the background. It wasn’t until 2003 that a historical marker was placed on the square of the courthouse acknowledging that the city of about 14,800 people was the site of the first trials.

Talk of commemorations or displays about the case came and went through the years, but nothing happened until the Scottsboro-Jackson County Multicultural Heritage Foundation was established by Washington. In December, it gained the use of an old church for the museum.

On Feb. 1, to mark the start of Black History Month, about 100 blacks and whites gathered in the old Joyce Chapel United Methodist Church on West Willow Street for the dedication of the Scottsboro Boys Museum.

The mayor attended, along with two white legislators and the granddaughter of the white judge who presided in one of the retrials in 1933 and threw out a jury’s guilty verdict against some of the defendants.

The fact that whites were part of the ceremony was meaningful to Washington, who worked 17 years on the project. Internet message boards have been peppered with negative comments and some whites, speaking privately, sneer at the idea of a museum “to that rape case.”

But the museum already has photos and press clippings about the case — some original and some copies — and a nearby museum is donating a juror chair used during the trial. Washington is hoping to get other items, including a jail table that may have been used by the defendants.

Some worry that the museum will dredge up hard feelings, but Garry Morgan sees it differently.

A white man who serves on the multicultural association and helped put together museum displays about the court case, Morgan said the new attraction is a chance for Scottsboro to recast itself before a modern audience.

“We want to end the negative stereotype of Scottsboro, to let the world know we’ve moved into the 21st century,” he said.

Associated Press