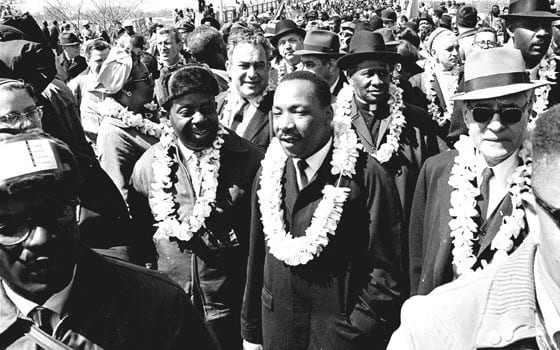

Author: AP /FileIn this March 21, 1965 file photo, Martin Luther King Jr. and his civil rights marchers cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., heading for the capital, Montgomery, during a five-day, 50-mile walk to protest voting laws. Before the 1964 “Freedom Summer” registration drive in Mississippi, just 5.8 percent of blacks in that state could cast ballots.

GREENSBORO, N.C. — The four college freshmen walked quietly into a Greensboro dime store on a breezy Monday afternoon, bought a few items, then sat down at the “whites only” lunch counter — and sparked a wave of civil rights protest that changed America.

Violating a social custom as rigid as law, Franklin McCain, Joseph McNeil, Ezell Blair Jr. and David Richmond sat near an older white woman on the silver-backed stools at the F.W. Woolworth. The black students had no need to talk; theirs was no spontaneous act. Their actions on Feb. 1, 1960, were meticulously planned, down to buying a few school supplies and toiletries and keeping their receipts as proof that the lunch counter was the only part of the store where racial segregation still ruled.

“The best feeling of my life,” McCain said, was “sitting on that dumb stool.”

“I felt so relieved,” he added. “I felt so at peace and so self-accepted at that very moment. Nothing has ever happened to me since then that topped that good feeling of being clean and fully accepted and feeling proud of me.”

They weren’t afraid, even though they had no way of knowing how the sit-ins would end. What they did know was this: they were tired, they were angry and they were ready to change the world.

The number of protesters mushroomed daily, reaching at least 1,000 by the fifth day. Within two months, sit-ins were occurring in 54 cities in nine states. Within six months, the Greensboro Woolworth lunch counter was desegregated.

The sit-in led to the formation in Raleigh of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which became the cutting edge of the student direct-action civil rights movement. The demonstrations between 1960 and 1965 helped pass the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

“Greensboro was the pivot that turned the history of America around,” says Bill Chafe, Duke University historian and author of “Civilities and Civil Rights: Greensboro, North Carolina and the Black Struggle for Freedom.”

On Monday, the 50th anniversary of that transformative day, the International Civil Rights Center and Museum opened on the site of the Greensboro Woolworth store. The dining room is still there, with two counters forming an L-shape. One counter is a replica because the fixture was divided into parts and sent to three museums, including the Smithsonian. But the original stools and counter remain where the four sat and demanded service.

The building remains because two men — county commissioner Skip Alston and city council member Earl Jones — arranged to buy it in 1993 for $700,000 from a bank that planned to turn the space into a parking lot.

“It is my fervent wish, hope and desire that this great edifice … will be a grand monument to the struggle of all people who strive for freedom,” said Blair — now named Jibreel Khazan — in a telephone interview. He took the new name in 1968 and has worked as a teacher, counselor, motivational speaker and storyteller.

McCain went on to become a research chemist and sales executive, while McNeil retired as a two-star major general from the Air Force Reserves in 2001 and also worked as an investment banker. Richmond died in 1990.

The four freshmen at N.C. AandT State University were part of an NAACP youth group started by Ella Baker, known as the mother of SNCC. They spent much of the fall semester discussing how to make real the unfulfilled promise of the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education.

Other sit-ins had occurred — in Durham, in 1957; in Oklahoma City and Wichita City, Kan., in 1958; and in several northeastern cities even before that. But they didn’t catch fire the way the one in Greensboro did.

The time was right, Chafe says: Six years had passed since the Brown decision that did away with the legal concept of “separate but equal,” but little had changed. Rosa Parks and the 1955 bus boycotts in Montgomery, Ala., also had faded into memory. And the place was right as well: Greensboro’s white leaders believed theirs was a progressive city and they wouldn’t stomach brutality.

And the four young men were right for the job too. Raised to believe in their country and themselves, they were ready to die if that’s what it took to end segregation.

McCain says he had tried to follow the advice of his parents and grandparents: Believe in the Bill of Rights and the Constitution; get a good education; respect your elders and do good deeds.

“I did all those things, but it was business as usual coming back from society in general,” McCain said in a phone interview.

He still had no dignity, no respect and few rights, all of which filled him with hate, “not for people but for a system that I thought had betrayed me.”

It was when McNeil returned to school on a bus from New York that they decided to act. As the bus traveled further and further south, the atmosphere became more and more oppressive. McNeil wasn’t allowed to dine at the restaurant in Richmond where the bus stopped so passengers could eat.

He became furious.

Few people expected a group of young men, just 17 and 18 years old, to be so determined, McNeil says. They underestimated the students’ ability “to take on something difficult and sustain the effort for a long period of time,” he said.

“We were quite serious, and the issue that we rallied behind was a very serious issue because it represented years of suffering and disrespect and humiliation,” McNeil says. “Our parents and their parents had to endure the onus of racial segregation and all that it did in terms of being disrespectful to human beings and the difficulties it places in so many ways of life, not just public accommodations, but in areas like employment and education.

“Segregation was an evil kind of thing that needed attention.”