Even in death, Brother Blue still stands tall.

The iconic Cantabrigian was honored last Friday at Harvard University’s Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research for his “significant contribution to African and African American culture, art, and life of the mind.”

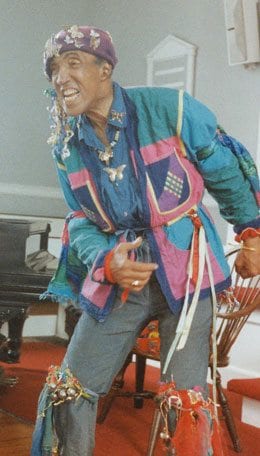

With a Ph.D. in storytelling, a master’s from Yale and a bachelor’s from Harvard, Brother Blue was certainly no stranger to intellectual brilliance. But it was his unusual career, unforgettable personality, unique contribution to local culture and “desire to build a better world, one story at a time” that earned him the W.E.B. Du Bois Medal.

The distinguished group of journalists, philanthropists, activists and academics who also received Du Bois Medals were: Charlayne Hunter-Gault, the award-winning journalist who, with Hamilton Holmes, de-segregated the University of Georgia in 1961; Vernon E. Jordan Jr., the lawyer and political adviser who worked on Hunter-Gault’s case at the University of Georgia and later as chairman of the Clinton Presidential Transitional Team; and Daniel and Joanna S. Rose, the philanthropists and founders of the Harlem Educational Activities Fund.

Also receiving awards were Bob Herbert, the New York Times op-ed columnist; Frank H. Pearl, the philanthropist and publisher who began Basic Civitas Books, a Perseus Books imprint devoted to publishing books in the field of African American studies; and Shirley M. Tilghman, president of Princeton University who initiated the creation of Princeton’s Center for African American Studies.

Hugh M. “Brother Blue” Hill was the hometown favorite, and the mere mention of his name triggered both applause and cheers. He spent the last 30 years telling stories that he believed could save the world, before passing away at the age of 88 earlier this year.

During the ceremony, Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, a Harvard professor of history and African American studies, recalled Brother Blue’s contribution to Harvard’s academic community.

“Brother Blue occasionally did come in from the street corner,” Higginbotham said, “and he was a frequent presence at the lecture series and the colloquia of the Du Bois Institute. Many of us here remember him well. An engaged listener, his questions, comments and poetry were always thoughtful and thought-provoking.”

She also said that Brother Blue made a “lasting impression” on other scholars who passed through the Du Bois Institute. Hope Lewis, a Northeastern law professor and former Du Bois fellow, was one of them. “I remember specifically his stories about the slave chains he carried,” she said. “[There were] lessons from Dr. Blue that we . . . never forgot.”

Before the event started, Henry Louis Gates Jr., the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and director of the Du Bois Institute, talked with the Banner about Brother Blue and recalled the colloquia that Blue attended. To conclude those events, Gates would say, “Blow us home, Brother Blue,” and Blue would then offer his comments. Because the colloquia were recorded, his “memory will live in the Harvard Archives,” Gates explained. “He will certainly not be forgotten.”

A video of Brother Blue’s impromptu version of King Lear was also shown at the ceremony, drawing laughter and tears from the audience.

Accepting the medal on behalf of her husband was Ruth Edmonds Hill, who wore a large blue butterfly necklace to honor Blue’s distinctive style. She said that Blue’s memory is still very much present in her life and explained that several days ago, she was looking for some paper. During her search, she found some paper with Brother Blue’s handwriting on it.

“Don’t hurt nobody,” it said. “And that was the way he lived,” she explained, as tears caused her to pause a moment.

Hill concluded her remarks by thanking the Du Bois Institute and quoting her late husband, “From the middle of the middle of me, to the middle of the middle of you,” prompting a standing ovation from the audience.