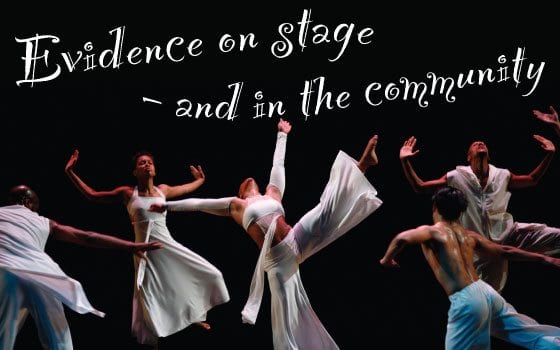

When he was 19 years old, Ronald K. Brown founded Evidence, A Dance Company. Now reaching its 25th year, his award-winning, critically acclaimed company performs throughout the world. And wherever they travel, they also teach master classes and conduct lecture-demonstrations for individuals of all ages.

Raised in the Bedford Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn, New York, where his great uncle founded Trinity Zion Pentecostal Church of Christ, Brown creates dances of riveting poetic force that transmit values and shared histories.

Brown, 43, has created a unique body of choreography that reaches across time, drawing from ritual movements of West African, Caribbean and Brazilian cultures as well as classical and modern dance traditions — and hip-hop. On his Web site, he states as his company’s mission to “promote understanding of the human experience in the African Diaspora through dance and storytelling … leading deeper into issues of spirituality, community responsibility and liberation.”

Last weekend, Brown, and his company were in Boston, where they performed three programs at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston as part of World Music/CRASHarts series of contemporary dance.

Brown began his stay on Friday morning by conducting a master class at the Boston Arts Academy. About 30 of the students were in attendance Friday evening, and stayed for a conversation with Brown and his company following the performance.

The Boston program presented a trilogy of dances choreographed by Brown.

Brown’s inspiration for the first work, “Two-Year Old Gentlemen” (2008) was the love between his late grandfather and 2-year-old nephew. Drawing from male initiation rites and challenge dances of Caribbean and West African cultures, the dance celebrates male resilience, competition, courage, and camaraderie. Its music combines a live recording of Bishop Paul S. Morton singing “I’m Still Standing” and a drum solo by West African percussionist Mohammed Camara.

The dancers—Brown, Donovan Herring, Sule Adams and Arcell Cabuag, represented males of different ages and Meckha Cherry’s costumes conveyed their varied ways of life. As the boy, Herring wore a shirt and tie and the others were garbed in assorted jackets and hats.

Herring seemed weightless as his feet pulsed in unison with the drums, as if lapping energy from the floor. Cabuag, his hair in a mohawk, has a small build but loomed large with his electrifying energy. Adams, a tall and muscular dancer with long limbs, moved his arms like windmills.

The lighting design by Dalila Kee accented the transition of the men from focusing on themselves to each other as, moving in circles and squares of light, they shed their jackets and shirts and formed pairs, lines and finally, with arms interlocked, joined in a circle.

The second work, “Incidents” (1998), takes its title from the 1861 autobiography of Harriet Jacobs, “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl,” which chronicles her journey from slavery to freedom. Brown’s program notes describe the dance as an exploration of how “the remnants of the slave narrative live in the body and actions of women.”

Tiffany Quinn, Clarice Young, Lilli Ann Tai, and Francine Ott performed the dance to the music of the Staple Singers, a live recording by Aretha Franklin at age 14 singing Thomas A. Dorsey’s gospel classic “Precious Lord,” and the infectious house-soul concoction “Mumbo Jumbo” by Wunmi Olaiya, who also designed the costumes.

Wearing white robes, Quin, Young and Ott suggest women at different stages of life. With her large body and regal bearing, Ott had the aura of a matriarch. Tai, a girl, wears a simple beige dress.

The dance opens with a long solo by Tiffany Quinn, whose eyes sparkle in the evocative lighting by Brenda Gray. Behind Quinn, as if performing a ritual, Young and Ott tenderly minister to the girl in a pool of light. As all four gradually move into a dance that evokes the life-sustaining bonds among women, Quinn performs a wondrous transformation from a vigorous woman in her prime into the figure of an old woman bent from labor, still moving with no let up in power.

After the performance, a woman in the audience said, “You see the strength of these women; but also the shadow of slavery that we all still feel.”

Commenting on Brown’s distinctive movement vocabulary, Boston Arts Academy senior Judelle Cummins, a dance major, said that unlike other companies, “They are way beyond just doing high extensions or turns. It’s about the feeling, the culture, the message.”

Jovanni Soto, a junior majoring in dance who also took part in the morning class, added, “You build the movement from your inner self.”

The evening concluded with Brown’s signature work, “Grace,” which the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater premiered in 1999.

Its music begins and concludes with Duke Ellington’s soaring gospel composition, “Come Sunday,” sung first by Jimmy McPhail, then by Jennifer Holiday. In between are “Gabriel and Rock Shock,” a pulsing soul-house track by Roy Davis, Jr., and the Nigerian Afrobeat hit “Shakara” by Fela Anikulapo Kuti. Performed by all eight dancers, including Brown, the dance seamlessly shifts from Ellington to hip-hop and back, finding exalting jubilation in each vein of music.

At first wearing red and white costumes and then dressed in white, with the men bare to the waist, the dancers moved from solos into duets, lines and circles. As their repetitive, rhythmic movement and whirling improvisations reached a peak, they evoked the ecstatic release of Shaker dancers or whirling dervishes. In the course of the work, Brown and his company moved from inwardly focused solos into pairs and groups and then, facing the audience as they danced in unison, drew all into their circle of grace.

After the performance, Brown and his company returned to the stage for a conversation.

Brown told the audience that, as a young dancer in New York, he “never saw real people on stage,” and wanted to engage “real bodies in making stories.”

His goal from the start has been to create “dances with purpose,” such as the traditional dances that mark life passages in African tribal cultures. But he is not stuck in the past. Brown’s choreography melds the rhythms of hip-hop and house music as well as the forms and techniques of contemporary and classical dance. “We do arabesques too,” said Brown. “We’re all part of a tapestry. We are evidence of the world we are living in.”