The past year did see some movement in the development of the city’s long awaited three-member civilian board charged with reviewing allegations of misconduct by members of the Boston Police Department (BPD).

But some critics in the community found the pace glacial — and troubling.

Headlining the plus side of the ledger: the board now actually exists. Mayor Thomas M. Menino announced plans to create the panel in August 2006, but it wasn’t officially established until this March, when the mayor signed an executive order bringing the newly named Community Ombudsman Oversight Panel (CO-OP) to life.

“It is in the best interest of the City of Boston and the Boston Police Department to have an oversight mechanism to build trust and confidence within the community,” Menino wrote in the order.

In the order, Menino laid out the panel’s responsibilities — to review complaints alleging serious misconduct that are dismissed by the department’s Internal Affairs Division (IAD), as well as a random sampling of other dismissed complaints; to request additional investigation by police if IAD case files are found to be lacking; to recommend action to the police commissioner if any is warranted; and to make an annual report to the mayor.

But it also set forth what some have called the board’s crippling limitations. CO-OP lacks both the power to conduct independent investigations and the ability to issue subpoenas, and any recommendations the ombudsmen do make will be non-binding.

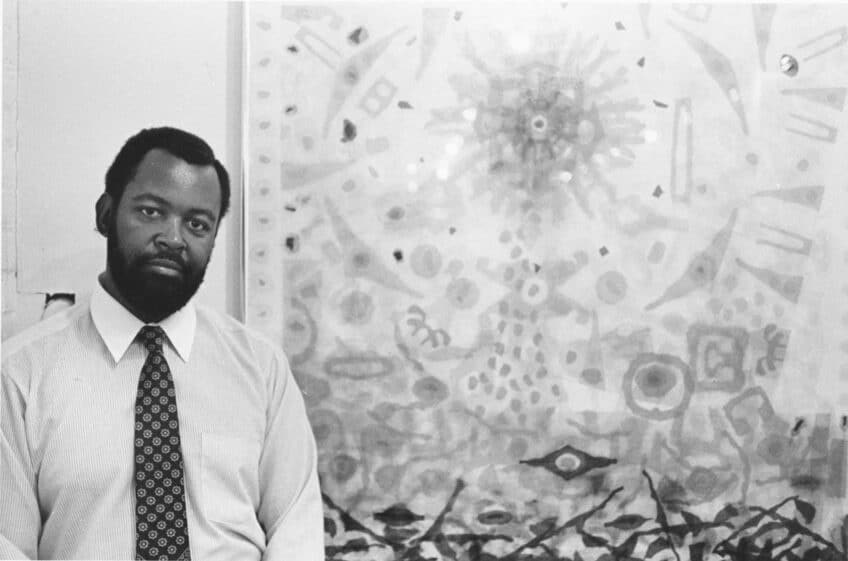

Another plus: The panel is stocked with talent. On Jan. 22, Menino appointed New England School of Law Dean John F. O’Brien, Northeastern University School of Law Professor David Hall and retired former state Parole Board member Ruth Suber to serve three-year terms as ombudsmen. The three have sterling professional reputations, and community leaders have applauded their integrity and apparent desire to serve Boston’s citizenry.

Attention later turned to operations, with Yola Cabrillana hired as the executive secretary to run point between police, complainants and panelists, and CO-OP stepping into its office space in IAD — a controversial location that many community and civil rights skeptics, like Urszula Masny-Latos of the National Lawyers Guild’s Massachusetts chapter, point to as evidence that the panel is at best compromised, and at worst powerless.

“The whole idea behind a civilian review board — the one that we had in our minds — was to create an independent body that would provide some oversight and look at complaints that come against the department or individual police officers,” she said. “How can you have people who are supposed to look at complaints about the department actually work within the department?”

The panel also now has its own Web site, www.cityofboston.gov/police/co-op — although, at this point, the online pickings are slim, offering only a brochure explaining the panel’s structure and responsibilities, bios of the three ombudsmen, and contact information to reach Cabrillana.

Squarely on the minus side: CO-OP remains light on hard accomplishments.

At an October meeting with city officials, community leaders and media, the ombudsmen confirmed that they had yet to begin reviewing cases, despite having completed their training in Internal Affairs processes, BPD rules and regulations, constitutional law and general police procedures several months prior. Panelists and city officials cited several reasons for the delay — most pointing toward the police.

Saying they were eager to get their hands dirty, the ombudsmen noted that a BPD lawyer and Superintendent Kenneth Fong, who heads IAD, had spent several months trying to hammer out a workable definition of “serious misconduct” and an acceptable method for how to select the random 10 percent of dismissed cases the ombudsmen must also review.

On top of that, board members said they are dependent on the BPD sending letters to complainants whose cases have been dismissed to let those citizens know they have the right to appeal to the CO-OP board. BPD officials said 20 such letters were sent between July and October, but they hadn’t received responses from any of the citizens. In fact, they said, they had no way of knowing whether or not the complainants ever received them.

The net result: no appeals had been forwarded.

At that October meeting, the ombudsmen and city officials responsible for getting the program up and running promised expanded outreach efforts to inform community members of developments with CO-OP, a move intended to bring the program closer to its ordered goal of helping to restore trust between Boston police and the citizens they serve.

But as the year draws to a close, those efforts — or any new information about what residents can expect in the coming year — have been decidedly quiet.

“Ultimately, it’s going to turn on whether we do this job right,” said Northeastern’s Hall at the October meeting. “I don’t know if there’s a silver bullet that will make everybody believe.”