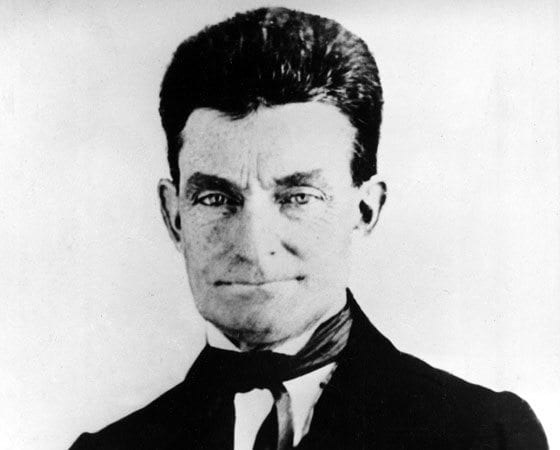

Author: APThis 1857 file photo shows John Brown, leader of the historic raid on the federal arsenal and armory at Harpers Ferry, W.Va. Brown, an abolitionist, and his followers attempted to bring attention to the plight of slaves in the United States, using armed force in the raid, which took place on Oct. 16, 1859.

HARPERS FERRY, W.Va. — A century and a half later, we still don’t know quite what to think of John Brown.

Certainly, he aimed to be a hero. He believed his plan was the necessary means to a righteous end: Storm a federal arsenal, seize thousands of weapons, arm a gathering guerrilla force and start the revolution that would end the morally reprehensible and perfectly legal institution of slavery.

Yet the first casualty of his 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry was a free black man, a baggage handler who bled to death on the street while Brown’s raiders grabbed hostages and holed up at a fire engine house.

Within 48 hours, Brown’s rebellion was dead, along with at least four civilians, 10 raiders and a U.S. Marine who helped retake the building.

Brown’s methods have been debated ever since, the grandiosity of his plot and his willingness to kill or be killed a timeless fascination. This year, the National Park Service has declared that his raid was the opening salvo in the War Between the States, with sesquicentennial commemorations beginning in West Virginia.

But in 1959, as America began to contemplate the centennial of the Civil War, Brown was largely left out of the discussion.

Segregation of schools and public lynchings still made headlines, and many white Southerners feared civil rights activists would use retold tales of the raid to agitate. Blacks feared being marginalized, or worse. And so John Brown was pushed aside, and the centennial began in 1961, with the anniversary of the Confederate firing on Fort Sumter.

“John Brown was, in effect, a terrorist, whether you agree that what he was doing was right or not,” says Gerry Gaumer, spokesman for the Park Service in Washington, D.C. “There are people in the Taliban who believe what they’re doing is right. Can you separate John Brown from what’s going on in Iraq or Iran or Pakistan or Afghanistan?

“They fervently believe what they’re doing is right,” he says. “But is there a better way?”

This month, the Park Service is offering two-mile walking tours that retrace Brown’s footsteps through the picturesque town at the confluence of the Shenandoah and Potomac rivers. Descendants of raiders, soldiers and townspeople will gather in August and then return for the Oct. 16 anniversary to explain their ancestors’ roles.

Had his own been among the bodies in 1859, Brown might have remained a bit player in the larger drama of the war. But that was not his fate. On trial for treason, murder and inciting a rebellion, he refused to apologize and declared the fight for freedom sanctioned by God and the Bible.

Swiftly convicted and executed, he became a potent and enduring symbol — to the North, a heroic martyr willing to die for equality; to the South, a lunatic killer attacking a way of life. And so he remained for a century or more, a complicated man often dismissed with simplistic labels.

Later, people began to talk more openly about slavery and the roles that blacks and other racial and social groups had played in the nation’s defining conflict.

Slowly, says historian Jean Libby of Palo Alto, Calif., historians stopped dismissing Brown as a madman and began to put him in the context of his times, times when — to the undying outrage of Brown and his wealthy supporters — courts ruled that black people were not citizens, but property of whites.

Textbook writers, Libby says, gradually began to acknowledge that slaves had come from Africa with culture and history of their own, in need of neither handlers nor teachers.

“Now slavery is portrayed differently,” she says, “and so is John Brown.”

Brown, a Connecticut native, had despised slavery since he was a boy and witnessed a slave being beaten. He spent months plotting to seize 100,000 weapons in what was then Virginia, retreat into the mountains and begin a guerrilla war with slaves who would join him, emboldened by his success.

“He was so ahead of his time,” says Alice Keesey Mecoy, who discovered she was Brown’s great-great-great granddaughter in 1976.

Libby had come to Mecoy’s grandmother, asking to photograph the family. Mecoy found the story “kind of cool,” but she was 16. Only after her own children had left home did she grow so interested as to make her ancestor’s life her full-time research project. This fall, the 49-year-old former accountant and office manager from Allen, Texas, is presenting a paper in Harpers Ferry on the women surrounding Brown. A book is in the works.

“He wasn’t only against slavery. He was for equality of all people, men and women, any color, any religion. He firmly felt everyone was equal,” she says. “And that was such a radical thought for the time.”

Mecoy, whose great-great grandmother Annie Brown stayed with her father at a farmhouse near Sharpsburg, Md., as he planned the raid, is proud of her ancestor. She’s pleased that “he’s no longer looked at as the crazy guy standing on a hill ringing a bell saying, ‘Come to me!’”

“You may have grown up being taught that he was this awful, terrible person who killed without provocation and stormed this armory and caused death, and the person in the next state may have learned a very different thing,” Mecoy says. “John Brown was taught regionally, based on what your region believed of him, and that caused differences of opinion. Now, I think we’re getting to where this is really the core of what happened.”

Harpers Ferry park ranger John Powell has talked with descendants of Brown who, like Mecoy, are quick to disavow the violence but who also admire that their ancestor “tried to right what he perceived as a terrible wrong.”

“To this day, when people speak of John Brown, the veins bulge in their foreheads,” he says. Those raised north of the Mason-Dixon line tend to see him favorably, while to many Southerners, “John Brown’s the bogeyman.”

“There’s an expression in the South: ‘I’ll be John Brown,’” Powell says. “It means I’ll be damned. Or I’ll be hanged.”

Brown became part of the popular culture of his times, and that legacy endures: An American reggae band uses the song as its name and Brown’s likeness on its album covers. In 2007, a rare daguerreotype of Brown sold for $97,750 at a Cincinnati auction.

Still, many people will discover Brown only this year. And as they do, they may wrestle with how to categorize him. History often presents people as one-dimensional characters, known only for good or evil deeds. Brown confounds because he committed both.

“People don’t know what to do with John Brown. They don’t know what color he is. They don’t know if he was a good guy or a bad guy. They don’t know whether they should teach their kids about him. They just don’t know,” says Bob O’Connor of Charles Town, a local college instructor and author of “The Perfect Steel Trap: Harpers Ferry 1859.”

“To me, he was a person that was single-focused on a cause that he was willing to die for,” says O’Connor. “I often ask my students, ‘What cause are you willing to die for?’ They have trouble coming up with the answer to that.”

While many defend Brown’s attack on Harpers Ferry, few label the slaughter of five pro-slavery leaders in Kansas three years before as anything but premeditated murder. Brown’s raiding party on Pottawatomie Creek hacked the men to death with swords in an execution that University of Maryland professor Martin Gordon calls “probably the most misunderstood event of his career.”

“Why did he use swords? Not because he’s a barbarian, but because he didn’t want anyone to hear what he was doing. Rifle fire would wake up the town” says Gordon, president of the Council of America’s Military Past.

“This was a very selective act of terrorism, moral justice, take your pick. Criminal action, take your pick,” Gordon says. “But he wanted to teach the pro-slavery element in Kansas a lesson, so he picked five of their leaders, pulled them out of their house and killed them as silently as he could.”

In his own death, Brown became what the pro-slavery New York Journal of Commerce predicted when it published an editorial urging that he be imprisoned rather than hanged for his crimes.

“Monsters are hydra-headed, and decapitation only quickens vitality, and power of reproduction,” the newspaper warned.

Escaped slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who had tried to talk Brown out of his doomed raid, acknowledged its importance decades later, in an 1881 speech in Harpers Ferry.

“Until this blow was struck, the prospect for freedom was dim, shadowy and uncertain. The irrepressible conflict was one of words, votes and compromises,” he said. “When John Brown stretched forth his arm the sky was cleared. The time for compromises was gone — the armed hosts of freedom stood face to face over the chasm of a broken Union — and the clash of arms was at hand.”

Even so, Dennis Frye, chief historian of Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, says Brown will remain “a perpetual enigma.”

“People emote when they think of John Brown. They’re not using their mind as much as their heart. They’re not using their brain as much as their soul,” Frye says. “They feel about John Brown. They either feel for him or they feel against him, but the key is they feel.

“I don’t see him passing away in the American experience or the American soul.”

(Associated Press)