Hundreds of blacks were being lynched each year. An early NAACP focus was the passage of a federal anti-lynching law, but it never happened. A flag reading “A Man Was Lynched Yesterday” often flew from the window of the group’s headquarters in New York City.

In 1917, the NAACP won its first Supreme Court case, a unanimous ruling that states could not segregate people into residential districts based on race. This was an early example of perhaps the NAACP’s most powerful argument: Equal rights are a fundamentally American value.

“We are the only country that was founded on an idea or a premise … the notion of equal citizenship,” says Taylor Branch, the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian of the civil rights movement. “Pretty much all of our history has tested what that meant. Most often the greatest crises have been around race.”

The NAACP framed its arguments as “something that was racial only because that was where America breached its promise,” Branch says. “Civil rights doesn’t mean black rights, it means rights pertaining to citizenship.”

This stance provided huge moral leverage.

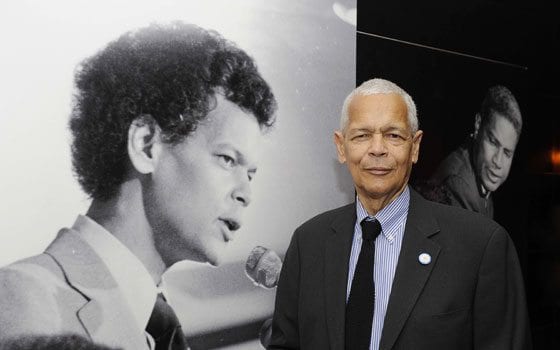

“Their power came from knowing they were right,” Bond says. “And even when the courts and the legislatures and the newspapers and the pulpits said they were wrong, they knew they were right, and they knew they would prevail.”

Power also came from thousands of average citizens like Levi Pearson, a South Carolina farmer. He agreed to be a plaintiff for an NAACP school desegregation case that became part of Brown vs. Board of Education.

Pearson’s credit was cut off and he lost his farm, and a local minister who helped with the case had his home and church burned down, says William Chafe, a history professor at Duke University.

“If you didn’t have farmers willing to put their lives on the line to go to court, you wouldn’t have cases that made up the Brown decision,” Chafe says. “Thurgood Marshall’s brilliance was the instrument of victory, but that brilliance was essentially rooted in the courage of ordinary farmers and workers.”

Those legal victories laid a foundation for many different groups to demand equal protection under the law.

“It spread to women, disabled groups, the elderly,” Branch says. “Most Americans are unaware of the things that it sparked, not just by other groups, but in areas other than school desegregation or race relations.”

Searching for identity in a new era

Before the recent presidential election, Myrlie Evers-Williams dug into her files and retrieved a slip of paper. It was a receipt for a poll tax, the payment system once used to keep blacks from voting.

Her husband Medgar, the NAACP’s field secretary in Mississippi, used to carry it in his wallet. It still has his blood on it.

“I don’t believe in living in the past,” says Evers-Williams, 75. “I also do not believe in forgetting the past.”

“So do I ever go back?” she asks of the era of humiliations and beatings and the murder of her husband by a white supremacist in the driveway of their home in 1963. “It never leaves me.”

That era came to a close with the great triumphs of the Civil and Voting Rights Acts.

After the killings of Martin Luther King Jr. and the Kennedys, some blacks turned militant and embraced violence as a tactic. Black Power was born. Marchers carried rifles instead of Bibles, raised black-gloved fists instead of picket signs.

To some, the NAACP began to resemble a new Booker T. Washington, out of step with the times.

Some of the group’s most significant post-’60s achievements, according to a timeline on the NAACP Web site, include helping keep conservative Robert Bork off the Supreme Court and ex-Klansman David Duke out of the U.S. Senate; registering hundreds of thousands of voters; leading marches; and pushing the issue of diversity in corporations and on television.

“In the second 50 years, I think their effectiveness has been reduced because they are perceived more as a group just trying to improve things for black people,” says Branch, the historian. “They don’t have that broader claim on the American heritage and mission.”

Danielle Belton, a popular blogger known as The Black Snob (http://www.blacksnob.com), has placed the NAACP on her list of “The Fallen,” between Michael Jackson and O.J. Simpson.

“It was partially a joke, and partially a critique,” Belton says. “They seem to have been unable to adapt to the post-1960s, to the new challenges in the black community. They’re stuck in their technique, in their mind-set.”

The NAACP reached a low point in the early 1990s, when it faced a $4 million deficit and lacked the funds to pay bills, salaries or even severance for laid-off workers.

Evers-Williams, who had belonged to the NAACP since Medgar gave her a membership on her 18th birthday, was asked to run for board chairman. She won by one vote. During her three-year tenure, she worked tirelessly to raise funds — Bond says her health suffered due to overwork — and she is credited with restoring the NAACP to prominence.

“I did not receive one cent of compensation for my work,” she notes, without bitterness. “It was something I felt I had to do. I was honored and blessed to fill that position.”

The culture wars and affirmative action battles of the 1990s kept race a polarizing topic even as the black middle class expanded and blacks cracked various glass ceilings. A civil rights backlash developed from decades of white guilt and new demands for black accountability.

“Black America’s main problem is neither overt racism nor more subtle ‘societal’ racism,” the conservative black scholar John McWhorter wrote in 2004. “Lifting blacks up is no longer a matter of getting whites off our necks. We are faced, rather, with the mundane tasks of teaching those ‘left behind’ after the civil rights victory how to succeed in a complex society — one in which there will never be a second civil rights revolution.”

In 2007, Bruce S. Gordon abruptly resigned as NAACP CEO because of differences with the unwieldy 64-member board, including Gordon’s desire to focus on practical solutions rather than political advocacy.

Reviving a legacy

Jealous, the new NAACP president, is 35 years old, and has a raft of ambitious plans such as “quality education for every child in this country” and reviving the group’s “legacy as a human rights organization.”

He says the NAACP has always set audacious goals, broken them down into smaller tasks, then kept focus on them for decades.

“Our job is to be the canary in the great American coal mine,” he says. “To scream when something is wrong.”

Jealous’ NAACP has a $21 million annual budget and 85 full-time employees. There are 525,000 members — 250,000 paid and 275,000 Internet “e-associates” — plus another 225,000 donors. The NAACP’s membership peaked at 625,000 paid members in 1964.

Last Thursday, it celebrated a century of struggle with its televised 40th Annual Image Awards, featuring stars like Halle Berry and Sean “Diddy” Combs. It also released a set of “challenges” for the Obama administration, such as ensuring there is no discrimination in the distribution of bailout and stimulus dollars, law enforcement accountability, health care and climate change.

The organization has filed recent lawsuits accusing 15 banks — many of which received bailout funds — of discriminatory lending and accusing Mississippi Gov. Haley Barbour of diverting funds meant for hurricane victims.

At the NAACP, the struggle will continue.

For those who see Obama as the leader of the “Joshua Generation,” named for the biblical figure who led Israel after Moses, NAACP board member Rev. Amos Brown points to the story of Joseph, who rose from slavery to a position of great power.

“Joseph was in the pharaoh’s palace, but the children were still outside in the brickyard, making bricks without straw,” Brown says. “We still have black folks today making bricks without straw. If we get caught up in the euphoria of this election and fail to deal with reality, it’s going to be a short-lived victory.”

(Associated Press)