NEW HAVEN, Conn. — The Ku Klux Klan was rising again, segregation was the law and Martin Luther King Jr. was not even born yet.

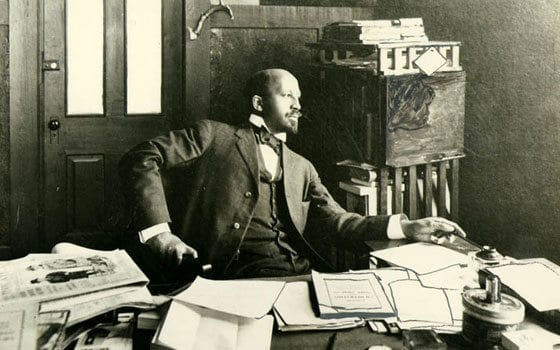

Amid the terror and oppression, civil rights pioneer W.E.B. Du Bois published a groundbreaking book in 1924 that challenged pervasive stereotypes of black Americans and documented their rarely recognized achievements.

His book, “The Gift of Black Folk: The Negroes in the Making of America,” detailed the role of black Americans with the earliest explorers to inventions ranging from ice cream to player pianos. He argued that blacks were crucial to conquering the wilderness, winning wars, expanding democracy and creating a prosperous economy by producing tobacco, sugar, cotton and rice, as well as by helping to build the Panama Canal.

“The Negro worked as farm hand and peasant proprietor, as laborer, artisan and inventor and as servant in the house, and without him, America as we know it would have been impossible,” Du Bois wrote.

Now, a new edition of the book is being published to mark the 100th anniversary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, which Du Bois co-founded. The new edition also marks Black History Month in February and arrives shortly after President Barack Obama’s inauguration.

“African Americans have served on the Supreme Court, in the cabinet, and, finally, as president of the United States,” Carl Anderson, supreme knight of the Knights of Columbus, wrote in the introduction. “‘The Gift of Black Folk’ allows us to fully appreciate these monumental achievements.”

Harvard University professor Henry Louis Gates Jr., who edited Du Bois’ works, including “The Gift of Black Folk,” welcomed the Knights’ reissuing their own edition. The book, which came during the Harlem Renaissance, sparked similar books that raised the nation’s consciousness of black Americans’ achievements, he said.

“Black people were using art and historical narrative as weapons in the civil rights movement, trying to show that black people were innately as intelligent as white people, that they weren’t distinctly inferior by nature, and the best way to do that, they felt, was by holding up the achievements of intelligent or artistic or creative black people,” Gates said. “And no one did this more brilliantly than the great W.E.B. Du Bois himself.”

Gates, who is considering contributing an introduction to the book, said he hopes the decision to issue a new edition “would augur a more liberal set of social policies for the Knights of Columbus.”

While the Knights are known these days for their socially conservative views on abortion and gay marriage, the organization has its origins in fighting anti-Catholic discrimination. The Knights, the world’s largest Catholic lay organization, published the original book as part of a series to combat historical accounts at the time that failed to recognize the achievements of minority groups.

Du Bois’ book highlights the role of blacks at crucial points in history.

A black man named Estevanico was the first European to discover Arizona and New Mexico after others on the expedition died. A black man accompanied Lewis and Clark, while Commodore Robert Peary, who discovered the North Pole, praised the work of his black assistant, Matthew Henson.

Blacks invented devices for handling sails, corn harvesters and an evaporating pan that revolutionized the method of refining sugar. A nother inventor created a machine for the mass production of shoes that was used by the United Shoe Machinery Company.

J.H. Dickinson and his son were granted patents for devices connected with player pianos. Granville T. Woods patented more than 50 devices related to electricity that were assigned to General Electric and other major companies.

The U.S. Patent Office at the time maintained records for 1,500 inventions by blacks — an incomplete record, Du Bois said. Black scientists did important work on insects and insanity.

Benjamin Banneker was a leading American scientist whose mathematical genius won the praise of Thomas Jefferson and led the slave owner to question notions of racial superiority.

Banneker played an important role in a survey as the nation’s capitol was laid out and studied methods to promote peace, suggesting a secretary of peace in the president’s cabinet, according to the book.

The book portrays Crispus Attucks, a runaway slave, as leading the fight against British soldiers that sparked the famous Boston massacre of 1770. Thousands of black soldiers fought on the American side of the Revolutionary War and distinguished themselves at the Battle of Bunker Hill and other sites.

Black soldiers and slaves helped save New Orleans during the War of 1812, winning praise from General Andrew Jackson. The New York Times praised the bravery of black soldiers in the Civil War.

“Without the active participation of the Negro in the Civil War, the union could not have been saved, nor slavery destroyed, in the nineteenth century,” Du Bois wrote.

In fighting slavery, blacks forced the country to expand its democracy and wound up winning rights for poor whites who did not own property, Du Bois argued. Their efforts also led to social reforms such as free public schools.

“Dramatically, the Negro is the central thread of American history,” Du Bois wrote. “The whole story turns on him, whether we think of the dark and flying slave ship in the sixteenth century, the expanding plantations of the seventeenth, the swelling commerce of the eighteenth or the fight for freedom in the nineteenth.”

(Associated Press)