LAWRENCE — Isabel Miranda got sick of watching roaches and mice scurry around with impunity in her apartment and finally called the local building inspector. Two weeks later, the 28-year-old mother of four got an eviction notice from her landlord.

“I figured, ‘Well, if he’s evicting me, I got to go,’” Miranda said.

But lawyers for Neighborhood Legal Services told Miranda she had options. Days later, Miranda was in Lawrence District Court, armed with documents and a lawyer.

Miranda was one of the lucky ones.

Soon, 20,000 low-income residents of Massachusetts like her will lose access to free legal help at a time when demand is growing.

The Massachusetts Legal Assistance Corp., the state’s largest funding source for civil legal aid, recently announced it is cutting aid grants by nearly 40 percent as its funding dropped from $22 million last fiscal year to $13.5 million this year.

State law requires all lawyers and law firms to establish interest-bearing accounts for client deposits, and pooled interest from those accounts are used to fund civil legal services for low-income residents. As a result of the economic downturn, the agency is expecting a 54 percent decrease in the income it receives from these accounts.

That means area legal aid groups, who already turn away more people than they can help, will have to decide which battered woman, which evicted family fighting foreclosure or which worker seeking back pay will have to go without legal assistance.

And there are few if any other alternatives, since law firms in the area have mostly reached the limit of their pro bono responsibilities, advocates say.

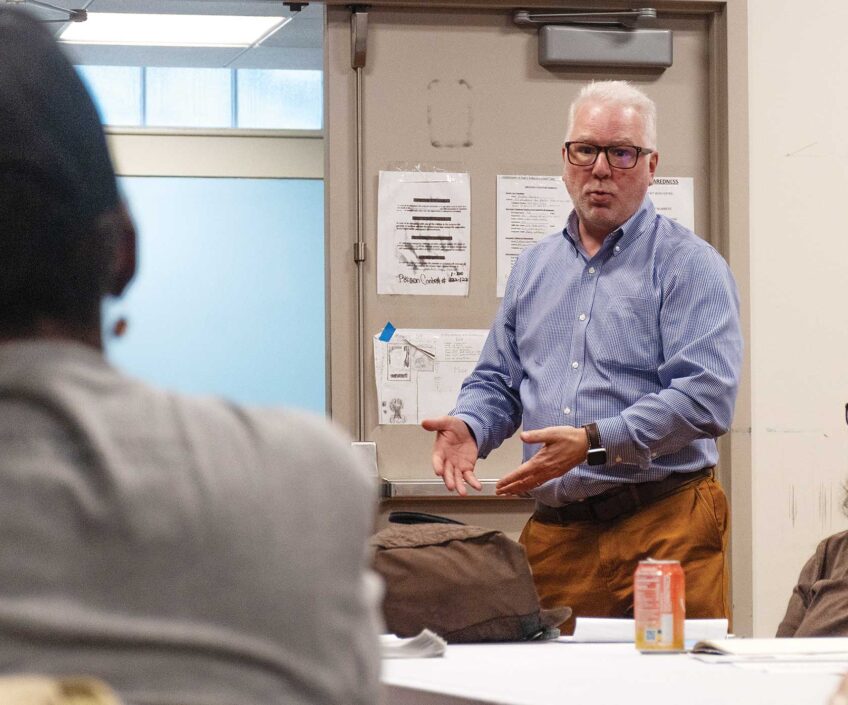

Lonnie Powers, executive director of the Massachusetts Legal Assistance Corp., said their interest-bearing accounts are suffering because of lowered federal interest rates and a dire housing market.

“And that’s despite the fact we were already turning away half of the people who were eligible to receive services and who came to us for help,” Powers said. Around 110,000 clients received free legal services last year, according to the group.

John Murphy, 43, of Salisbury, said without the legal aid, he’d probably be fighting his tenant case himself because he can’t afford a lawyer.

“And I’m not really good at vocalizing for myself,” said Murphy.

An unemployed plumber and a single father of a 9-year-old daughter, Murphy was fighting his landlord to fix a gas leak in his apartment. The gas leak, he believed, was responsible for getting his daughter sick with headaches.

It’s unclear just how long legal aid groups will have to deal with cuts in funding, Powers said. Since the accounts are tied to the economy, it may take months — maybe years — before legal aid groups get back some of the lost funds, Powers said.

Robert A. Sable, executive director of Greater Boston Legal Services, said his group is expecting a 13.5 percent reduction in funding.

“With a cut of this magnitude, we’ll probably serve 2,000 fewer people than we do now,” Sable said. “There is almost no other place to refer people.”

Sheila Casey, executive director of Neighborhood Legal Services, said they are expecting a 29 percent drop and now won’t be able to fill an open attorney position.

“It will be hard to make up all of that shortfall without some impact on our staff,” she said.

Massachusetts is not alone. Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and the District of Columbia are all expecting deep declines in legal aid to low-income residents due to similarly dwindling interest-bearing accounts.

Legal aid groups in those states say they, too, are looking at hiring freezes, reducing work schedules and possible attorney layoffs. The groups say they will also have to cut back on the number of low-income residents who will receive free legal services.

That spells trouble for residents in poor cities like Lawrence. The northern Massachusetts city, where around 70 percent of residents are Latino, has the highest foreclosure rate in the state. A large number of those Lawrence residents fighting foreclosures, Casey said, are what legal aid groups call “innocent victims” — renters who keep paying rent to landlords even though the landlords fail to tell renters the bank has foreclosed on the property.

That’s what happened to Juan and Isabel Muneton. A bank recently gave notice to the couple, both 62, that they had a month to move out of their Lawrence apartment because of a foreclosure, even though their landlord never informed them.

For now, though, the couple has a Neighborhood Legal Services lawyer on their case and they remain in the apartment. But if the case drags, Isabel Muneton worries they and others like them will be on their own.

“Everything is so confusing,” said Muneton in Spanish. “We don’t know why this is happening.”

(Associated Press)