While it’s often said that art has a way of imitating life, its capacity for shedding light on long-forgotten and dark parts of history is sometimes overlooked. “Voyeurs de Venus,” the play that kicks off local theater group Company One’s 10th season, examines one troubling piece of history that still affects the black psyche today — the tragic tale of the “Hottentot Venus.”

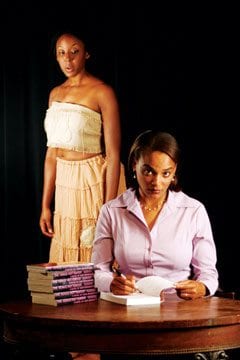

The play revolves around the story of Sara Washington, a black cultural anthropologist and college professor who is writing a book about the Venus, a 19th-century sideshow sensation whose real name was Saartjie Baartman.

Baartman was an ethnic Khoikhoi South African woman who was put on display in sideshow attractions throughout Europe during the 1800s because she possessed physical features, including buttocks and labia, considered unusually large by Europeans at that time.

As she writes, Washington finds herself forced to consider her own racial identity, comparing herself to Baartman, assessing her relationships with her white husband and her black lover, and struggling with a host of other issues.

Playwright Lydia Diamond started writing “Voyeurs” six years ago while living in Chicago and attending Northwestern University. Diamond, whose stage adaptation of Toni Morrison’s novel “The Bluest Eye” was performed by Company One last year, said that writing the play “freed up” some of her own thinking on being a black woman in America.

“The play is a very fragmented reality with a painful context,” she said. “Writing it opened up a discussion on race with myself.”

Actress Kortney Adams, who plays the lead role of Washington, said she had to reexamine her blackness for the role.

“We need to understand as black women this is part of our history,” Adams said. “But there are many people who don’t want to tell Saartjie’s story, because they are afraid to talk about race and class. We need to think about Saartjie’s place in history.”

The story can be troubling. In the period following the passage of the British Slave Trade Act in 1807(which abolished the trade of slaves in the United Kingdom), Baartman’s exhibition created a scandal among abolitionist groups. They believed that her treatment, which they likened to that of a caged animal in a zoo, was another form of slavery.

The treatment only worsened after Baartman died in 1815. Following her death, her skeleton, preserved genitals and brain were placed on display in the Musée de l’Homme (Museum of Man) in Paris until 1974, when they were removed from public view and stored out of sight. Nearly three decades later, in 2002, Baartman’s remains were brought back to her homeland of South Africa and laid to rest.

“One of the challenges of playing Saartjie was that there isn’t much written about her from a historical perspective,” said actress Marvelyn McFarlane, who portrays Baartman in the play. “It was a very difficult process to portray a real person who had a challenging, multidimensional life.”

With little in the historical record to draw on, McFarlane looked within.

“As a black female, I know how it is to not be looked as a human being,” she said.

The play’s two female leads are both manipulated by the men in their lives. Baartman is taken advantage of by Georges Cuvier, the French naturalist who created detailed drawings of Baartman’s anatomy and, upon her death, claimed her body for science, making a wax cast of her genitalia. College professor Washington is pushed by her black lover, publishing bigwig James Booker, to produce a book about Baartman’s story that will result in mainstream success, even if it means exploiting the memory of a woman who suffered greatly in life.

Throughout the 37-scene play, audience members get an idea of the hardships Baartman faced and the complexities of her life, as well as how the legacy of degrading imagery of black women continues today in popular culture.

Both McFarlane and Adams agree, however, that more positive images of black women such as Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and tennis stars Venus and Serena Williams balance out the negative portrayals. The actresses said they hope the play will open up more discussion on the topic.

“Saartjie has a tragic story,” McFarlane said. “But we hope black women don’t always have to be put into one block. Black women should be seen for what they have, both inside and outside.”

“Voyeurs de Venus” runs through Nov. 22 at the BCA Plaza Theatre at the Boston Center for the Arts, 539 Tremont Street, Boston. Please note the play contains some nudity and mature themes.

Tickets range from $15-$38. For show times and tickets, call 617-933-8600, visit www.bostontheatrescene.com, or purchase them in person at the Calderwood Pavilion at the Boston Center for the Arts, 527 Tremont Street, or the Boston University Theatre Box Office, 264 Huntington Avenue.

For more information, visit Company One’s Web site at www.companyone.org.