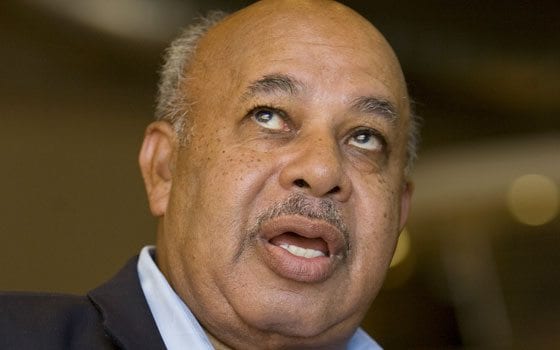

OMAHA, Neb. — When it comes to Ward Connerly, the California businessman on a state-by-state war against affirmative action, it’s hard for many people on either side of the issue to be colorblind.

If he were white, his message that racial preferences are damaging to everyone would ring hollow. As a black man, his positions have inflamed some supporters of affirmative action who have called him “race traitor” — or worse.

He’s succeeded in three states, faltered in a few others, and now he’s looking to Nov. 4, when voters in Nebraska and Colorado will decide initiatives he helped put on the ballot.

Critics question his tactics in gathering signatures and what he gets paid for his efforts. But Connerly, a 69-year-old grandfather who can be mild and charming or harsh and defensive, is convinced that his mission of dismantling preferences is altering the course of history.

Affirmative action has become entrenched in American life and state by state, Connerly said in a recent interview with The Associated Press, and “we’re changing that.”

“If I thought it could be done — poof — flash of the wand, I’d be naive,” Connerly said.

Affirmative action, he said, is an antiquated system that, rather than helping minorities, reinforces the perception they are second-class citizens who need help to succeed.

Connerly’s proposed constitutional amendments prohibit state and local governments from giving preferential treatment to people on the basis of race, sex, ethnicity or national origin.

His fight against preferences started in the 1990s after a couple came to him when he was a regent at the University of California to talk about their white son’s failure to get into the system’s medical schools.

They showed him evidence that the schools were picking less qualified minority students, and Connerly became convinced the university was treating applicants unfairly.

In a battle that drew the attention of national media and the Rev. Jesse Jackson, Connerly persuaded other regents to adopt his proposal to ban the use of race- and gender-based affirmative action in admissions and hiring, a precursor to a statewide ban.

After victory in California, Connerly took his new mission to other states. It took more than three years to pass the measure in Michigan, and he also succeeded in Washington. He formed the American Civil Rights Coalition, which has bankrolled campaigns across the country.

Connerly is accused of misleading voters by billing the initiative drive as a civil rights cause. Opponents say thousands of people are duped into signing petitions and voting for the measures because they’re described as bans on discrimination instead of attacks on programs that help women and minorities.

The group Nebraskans United, which formed to try to defeat the measure here, gave Nebraska Secretary of State John Gale video and other evidence that petition circulators left petitions unattended and committed other violations of state law.

They’ve filed a lawsuit challenging signatures’ validity because of a “pattern of fraud and illegality.” If successful, the lawsuit won’t keep the measure off the ballot but could keep votes from being counted.

Meanwhile, a national group is questioning how much money Connerly makes. Kristina Wilfore, executive director of the Ballot Initiative Strategy Center, which opposes Connerly’s efforts, said his compensation is “out-of-whack with any nonprofit industry standards.”

“Ward Connerly has used voter fraud and deception to place his initiatives on the ballot and profited off a campaign to outlaw equal opportunity,” Wilfore said.

Said Connerly: “Why would I have to do that when I had a very successful company from which I earned far more than I could make running a national nonprofit effort that resulted in significant abuse to me and my family?”

Connerly said he’s paid about $300,000 a year by the organization he founded to take his initiative beyond California.

At his Sacramento consulting firm, Connerly and Associates, which originates home repair loans and serves as the administrative arm for professional trade associations, he earned $2 million a year. He stopped taking a salary from the firm in 2005.

Connerly was born in 1939 in Louisiana, then moved with his family to California. He married a white woman, Ilene. Interracial marriage wasn’t common in 1962, and the union estranged them from her family until their son was born, Connerly wrote in his 2000 memoir, “Creating Equal: My Fight Against Race Preferences.”

But Connerly calls “black” and “white” superficial descriptors. In his own case, Connerly said, “black” actually means French Canadian, Choctaw, African and Irish American.

Connerly said he hopes Barack Obama, the Democratic nominee for president, might address the issue if elected. Obama is the son of a black man and a white woman.

“I may be wrong, but I honestly think that Sen. Obama, in an ideal world, would like to get rid of race as an issue in American life,” Connerly said. “I really believe that. And I’m not an Obama supporter.”

It may be unlikely, since Obama has said he opposes Connerly’s efforts to end affirmative action.

Connerly predicts Republican nominee John McCain — who has said he supports the measures — “would ideally like to leave [the issue] alone” if elected.

“Although he supports the initiatives, I believe he would just as soon that it go away,” Connerly said. “He doesn’t want to come across as hostile to black people and Hispanics.”

(Associated Press)